News

Oliver Sacks Quotes On Empathy, Illness, & Music

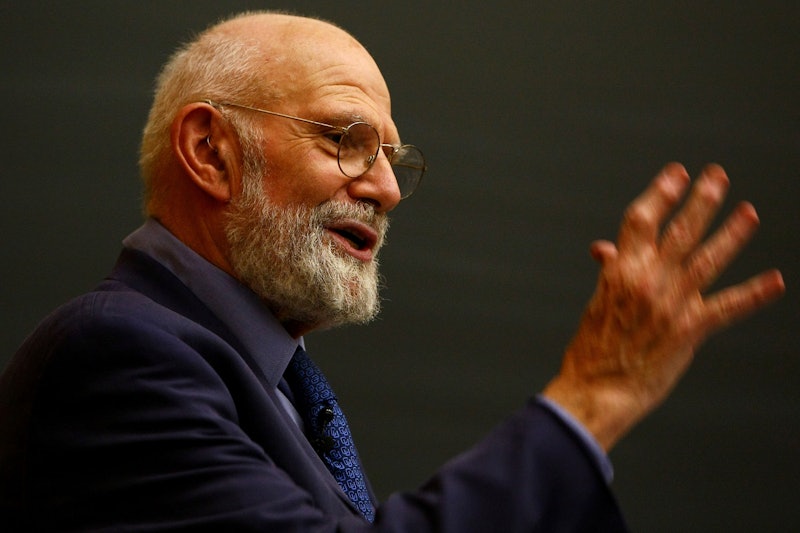

Renowned neurologist and author Oliver Sacks died of cancer Wednesday, according to The New York Times. Some of Sacks' best-selling books, including The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat and Awakenings, were adapted for the stage and the big screen because they were some of the first books published by a doctor that helped humanize people who suffered from neurological illnesses and disorders. Sacks told his patients' stories in his characteristic dramatic and quirky way in an effort to "imagine what it was like for them" and help the general public grasp a better understanding as well. Some of Oliver Sacks' best quotes are telling of his empathy as a doctor, while others show just how eager he was to understand the mind.

In his studies, Sacks hoped to understand the strangest of the mind's strange pathways. He said he studied hallucinations, for example, as the result of his experimentation with LSD while he was younger, according to NPR. Sacks was a lover of music, philosophy, and enjoyed taking swims around City Island in the Bronx, where he lived for years, according to the Times. The Times described Sacks as a man of contradictions: "candid and guarded, gregarious and solitary, clinical and compassionate, scientific and poetic, British and almost American." Some of Sacks' best quotes reveal these qualities and his great appreciation for the mind.

Sacks received about 10,000 letters a year, according to the Times. He once described how he decided which ones to respond to with hilarious simplicity:

I invariably reply to people under 10, over 90 or in prison.

In his book Musicophilia, Sacks beautifully described the importance of music to him and his patients, according to Goodreads:

Music can lift us out of depression or move us to tears — it is a remedy, a tonic, orange juice for the ear. But for many of my neurological patients, music is even more — it can provide access, even when no medication can, to movement, to speech, to life. For them, music is not a luxury, but a necessity.

In a 1986 interview with People, Sacks' reason for studying people with neurological disorders like Asperger's syndrome or Tourette's syndrome made a poignant statement about how society views people with mental illnesses or disorders:

I love to discover potential in people who aren't thought to have any.

Sacks had a way of understanding that people with mental disorders are not the essence of their diagnosis. He understood them as people living with a condition — not as a condition defining a person, according to Goodreads:

In examining disease, we gain wisdom about anatomy and physiology and biology. In examining the person with disease, we gain wisdom about life.

Sacks struggled with his own neurological disorder, a condition called prosopagnosia, or face blindness. Sacks suffered from such severe face blindness that he once didn't recognize his personal assistant of six years in the lobby of a Manhattan office building even though he had gone there to meet her, according to MinnPost. But Sacks was so lighthearted about life and his own problems that he has joked openly about his struggles, according to the program Radiolab:

Several times I have started apologizing to large, clumsy, bearded people and realize that it's a mirror. But it's even gone a stage further than that. Fairly recently, I was in a cafe in Chelsea Market with tables outside and while I was waiting for my food I was doing what people with beards often do: I started to preen myself and then I realized that my reflection was not doing the same thing. And that inside there was a man with a beard, possibly you, who wondered why I was sort of making faces at him.

Sacks seemed to understand that doctors need to humanize their patients while also diagnosing and treating them appropriately, according to The Economist:

Although it's up to me as a neurologist to diagnose the disease and to think in therapeutic terms, I always want to address the person as much as the disease, and I'm very glad my own doctor feels similarly. I'm not just a case to him, I'm a person responding to the situation. So I somehow sit between the biology and the humanist point of view.

Sacks loved life, even in old age, according to an op-ed he wrote for The New York Times:

At nearly 80, with a scattering of medical and surgical problems, none disabling, I feel glad to be alive — "I'm glad I'm not dead!" sometimes bursts out of me when the weather is perfect.

When Sacks learned he had terminal cancer, he wrote about his feelings for the Times. His words show that he has a deep understanding of the mind and an inspiring view of life:

I cannot pretend I am without fear. But my predominant feeling is one of gratitude. I have loved and been loved; I have been given much and I have given something in return; I have read and traveled and thought and written. I have had an intercourse with the world, the special intercourse of writers and readers. Above all, I have been a sentient being, a thinking animal, on this beautiful planet, and that in itself has been an enormous privilege and adventure.