Books

A Shocking Death Starts 'Black-Haired Girl'

Robert Stone's Death of the Black-Haired Girl (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt) is a captivating tale about the untimely death of Maud Stack, a highly spirited and intelligent college girl. It is untimely because it occurs in public — Maud is killed in a hit-run that rips her body apart, leaving it “partly against two brownstone steps and partly against the spear tips of the railing that guarded a house three doors down” — and because it occurs just after she has a fight with Steve Brookman, the married professor with whom she’s sleeping.

The mystery of Maud’s death, however, is only a single component of this story; the tailspin into which it sends the book’s characters seems to be the story’s true meat, rather. (This decision, to focus on the aftermath rather than the circumstances, seems to be something of a shared impulse among contemporary writers. Take, for example, Jennifer duBois’s Cartwheel.) Brookman must at once deal with Maud’s death and the ignominy of the circumstances — their fight was very public, and happened in front of Steve’s wife Ellie. Maud’s father must deal with another death in his family, with Maud’s mother having died when the girl was young. These are men who, even when they do find the answer to Maud’s death, aren’t granted solace, because it is the psychological aftermath, not the factual that irks them.

In his mid-70s, and with a career that has spanned decades, Stone has a sizable list of works to his name at this point. That list includes, for example: Hall of Mirrors; A Flag for Sunrise; Children of Light; Dog Soldiers, which won the 1975 National Book Award; and Bear and His Daughters, which was a finalist for the 1997 Pulitzer Prize.

In Black-Haired Girl, these credentials show through in the author’s masterful control of the plot. He holds readers in suspense, constantly, and anxiously, wondering if this character is at fault or if this detail is significant. Abortion, for example, shows up early on in the novel, and in the way that would make readers suspicious, and therefore more invested. We are introduced to a schizophrenic homeless man wanders the campus and likes to watch Maud. And to Jo Carr, who counsels students considering abortion. And Maud is shown sneering at anti-abortion ralliers carrying graphic pictures of fetuses. These are just a few of the several menacing plot lines Stone dangles.

Stone’s work with tabloids, however, seems even more crucial to the construction of this modern-day noir novel. As a young man, Stone supported himself by writing for tabloids; these tabloids, though, were significantly different than their contemporary descendants. In Stone’s day (the middle decades of the 20th century), tabloids’ main course was fictionalized, or completely fictitious, stories about horrible things done to pretty young girls, instead of the celebrity gossips that graces the covers of today’s supermarket-aisle publications. Stone’s job, which the author described for The New Yorker, was to write attention-grabbing headlines for these stories of grisly murders. He, therefore, needed to know what would turn heads, send a child down the spine, and play upon the nerves. (That is, I suppose, why use the world “sensational” to describe such publications.)

Stone, therefore, shows a comfort with writing the sensational that is rare among distinguished authors of literary fiction today. His characters are, in fact, very much types. Maud is the manic, hypersexual coed. Brookman is the disillusioned and burnt-out college professor. The archetypal nature of Black-Haired Girl’s characters may bother readers of literary fiction at first, but one must remember that these characters aren’t ultimately meant to be nuanced explorations of the human condition. Stone obviously takes comfort in the fiction-ness of fiction, too, writing in The New Yorker that his more factual tabloid stories, ones about gruesome deeds done by humans against another, irked him: “The notion that what we were publishing reflected human behavior was disturbing.”

But then again, the contours of this novel — the disgrace of a college professor, the death of a passionate college girl — aren’t unbelievable, at all, even if its characters are cardboard cut-outs of people. But perhaps this is necessary. Stone, as the quote suggests, seems to know that the heavier the lacquer of fiction, the more the unsavory is made palatable.

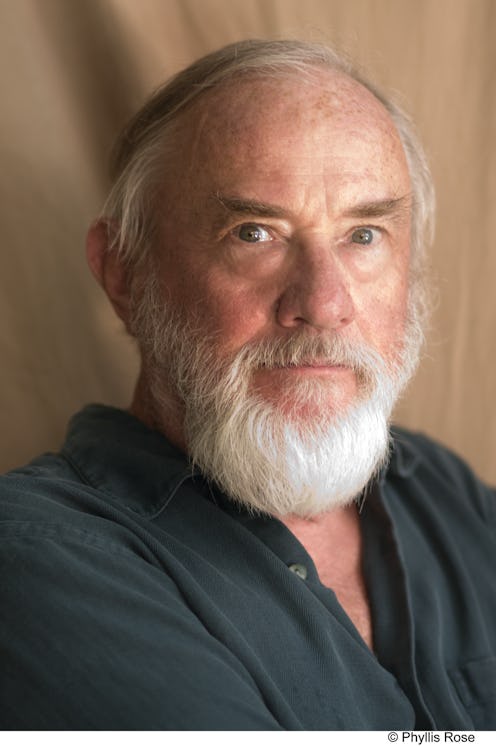

Image: Phyllis Rose