TV & Movies

What Elvis’ Colonel Tom Parker Was Really Like

Everybody loves Tom Hanks — but they may not love Tom Parker, the predatory music manager he plays in Elvis.

Viewers who are more familiar with Elvis Presley’s music than his life story might be surprised by the prominence Colonel Tom Parker (Tom Hanks) in Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis biopic. But big Elvis fans know Parker — the man who managed the musician’s career from 1955 until the iconic singer died prematurely in 1977 — all too well. Parker was a svengali who exerted an extreme amount of control over his charge’s career, and took enormous 25 to 50% in commission. Despite Parker’s troubling exploitation of Presley, though, he undeniably succeeded in catapulting him into a new echelon of fame — and, now, legend.

Speaking to Stephen Colbert on The Late Show last year, Hanks described Parker as “both a genius and a scoundrel … He was a very disciplined man, but also a guy who you might want to check your wallet to make sure you still have all those fives and 10s.” Most surprisingly, Hanks described asking Elvis Presley’s ex-wife Priscilla about Parker, and getting a surprising answer. “I was expecting to hear stories about the distrust she had for ‘Colonel Tom’ Parker over these many years,” he told Colbert. “And she said, ‘No. He was a wonderful man, and I wish he was alive today. He took really great care of us. He was a scoundrel in his way.’”

A deeper look into Parker’s biography reveals more of his genius — and his exploitation of Presley. Read more to discover the real story behind the man who made Elvis.

Who was Tom Parker?

Throughout his life, Parker claimed that he had been born Thomas Andrew Parker in Huntington, West Virginia, shortly after the turn of the 20th century. In fact, as Smithsonian Magazine writes, Parker was born in Breda, in the Netherlands, in 1909, and his birth name was Andreas van Kuijk. At some point, he made his way to the United States — Smithsonian speculates that he entered through the Canadian border — and resided in America for the rest of his life as an undocumented immigrant. In spite of this fact, he served as a private in the U.S. Army in the early 1930s, and in 1932 was briefly incarcerated for desertion after leaving his unit without permission for leave. According to biographer Alanna Nash, Parker was diagnosed as a psychopath and discharged. (Despite his unofficial title, he was never a colonel: Louisiana governor Jimmie Davis granted him an honorary colonelcy in 1948, and Parker clung to it for life.)

After being discharged from the army, he spent time traveling with circuses as a carnival worker. The timeline of Parker’s life at this point is not entirely clear — no doubt due to his own desire to cover up his shabby early days — but in their obituary of him, The Daily News of Los Angeles wrote that he even founded his own circus, the Great Parker Pony Circus, and his own circus act, Colonel Tom Parker and His Dancing Chickens, in which chickens “danced” on a hot plate while music was playing. In 1935, he married Marie Mott, and they made their home in Tampa, Florida. There, The New York Times’ obituary reports, he pursued other eclectic pursuits including working as the city’s dog catcher and setting up a pet cemetery. He also grew estranged from his family: The South Florida Sun-Sentinel writes that his mother did not hear from him between 1933 and her death in 1958, while The Smithsonian describes his sister Nel Dankers-van Kuijk discovering that he was Elvis Presley’s manager after seeing them together in a magazine in 1960.

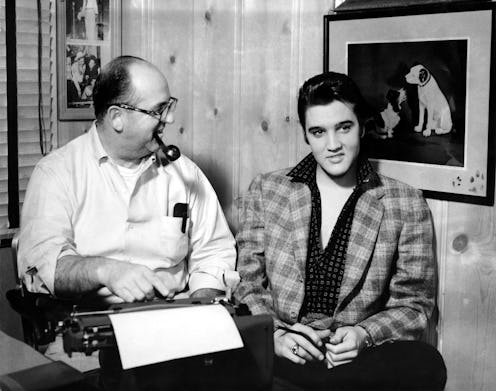

Eventually, Parker began to manage musicians. He began with country singer Eddy Arnold in the late 1940s, and his behavior toward Arnold foreshadowed how he would later approach managing Elvis Presley: Per the Times, he literally moved into Arnold’s family home in Nashville. Although Parker successfully landed Arnold performances in Las Vegas and acting roles in movies, Arnold evidently found his management style claustrophobic, because he fired him in 1953. Parker briefly managed another country star, Hank Snow, before meeting Presley in 1955.

What was Tom Parker’s relationship with Elvis like?

In 1955, Parker began advising Elvis Presley, who at that time was signed with a small recording label, Sun Records. That year, the small, struggling label sold Presley’s contract to RCA Victor for $35,000. Presley’s first single with RCA was “Heartbreak Hotel” — an instant classic that RCA disliked at first due to its lyrics, which told the story of a lonely man’s death by suicide. Presley, however, was confident in the song, and “Heartbreak Hotel” was soon at the top of the Billboard Charts. Parker quickly set to work promoting Presley, arranging tour dates and television appearances (including Presley’s famous performances on “The Ed Sullivan Show”), and by the end of 1956, he and Presley had signed a contract making Parker the musician’s “sole and exclusive adviser, personal representative and manager.”

Parker quickly set out to turn Presley into more than just a successful musician. In 1956, Elvis also starred in a hit movie, Love Me Tender. That alone would have raised the burgeoning pop star’s profile, but Parker didn’t stop there: As the CBC describes, he set up a deal with a movie merchandiser to produce dozens of Elvis-themed products, many of which were aimed at teenage girls. These branded Elvis products included jewelry, record players, and lipstick that bore the slogan, “Keep Me Always On Your Lips.” But Parker didn’t stop there: He even arranged for the sale of buttons that read “I Hate Elvis” and “Elvis Is a Jerk.” In other words, he’d monopolized the Elvis merchandise market — and raked in 50% of the millions of dollars in profit.

Parker also controlled Presley’s public image, engineering the kinds of movies in which he appeared and dictating his press appearances. According to Norman Taurog, a film director who worked with Presley, “the powers that be at MGM and Colonel Parker … always wanted [Presley] in lighter films surrounded by pretty girls” — so those were the films he made. In February of 1957, historian Michael T. Bertrand writes, Edward R. Murrow invited Elvis to appear on his prestigious evening news program. But Parker insisted that Presley be paid for his appearance, and when Murrow refused, the show was canceled. Smithsonian reports that Parker even restricted Presley from touring internationally due to his own undocumented status, forfeiting a potentially enormous payout.

Over the course of their long relationship, he exerted a remarkable level of control over the star, who put up with him until his death in 1977. In a review of a biography of Parker in The Washington Post, book critic Jonathan Yardley reflects that “The hold [Parker] had on Presley is an enduring mystery.” Presley remained loyal to Parker, even as Parker exploited and benefited from his star power and talent. But Parker, even later in life, was unrepentant: In The Daily News of Los Angeles’ obituary, he’s quoted as saying, “I sleep very good at night. When [Presley’s family and associates have] done all they can with him, then they start picking on me … I don’t think I exploited Elvis as much as he’s being exploited today.”

What happened to Tom Parker after Elvis’ death?

The hold that Parker had over Presley did not extend to Presley’s family. The Presley estate sued Parker for fraud in 1981, specifically over the deals he had with RCA in addition to his contract with Presley — which, needless to say, amounted to a conflict of interest. He lost his rights to Presley’s millions, and got into further legal trouble with RCA, to whom he ultimately sold Presley’s master recordings in order to stave off further litigation.

His first wife, Marie, died in 1980. He moved to Las Vegas and in 1989 got married a second time, to a woman named Loanne. In Las Vegas, he worked as an adviser for Hilton Hotels, consulting on entertainment. But as the L.A. Times wrote in its obituary of Parker, his life slowed down and shrank after Presley’s death. Despite his unpopularity with Presley’s relatives at this time, he refused to write a tell-all book about his years with the singer. Privately, though, he loved to reminisce: As Bruce Banke, a former publicity director for the Las Vegas Hilton, told the L A. Times, “He was usually in good spirits, talking about the carnival days, the Eddy Arnold days, the Elvis days. I just wish I had a microphone so I could have recorded it all. But it’s gone now.”

Parker died on January 21, 1997, of complications from a stroke. He was 87 years old.