Books

Is There A Better Way To Write About Interracial Friendship?

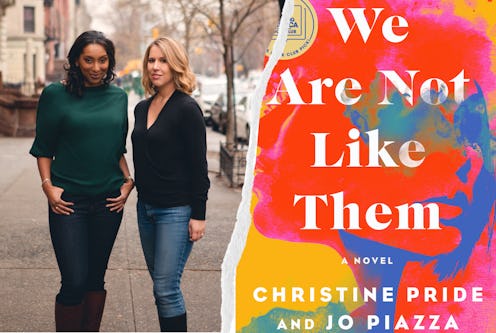

Co-authors Christine Pride and Jo Piazza talk about their new book, blind spots, and some statistical awakenings.

When Christine Pride and Jo Piazza started co-writing the book We Are Not Like Them, they wanted to zero in on a contemporary friendship. “We wanted full humanity, presence, and dimension [for] all of the characters that were part of the story,” says Pride, who’s a former Simon & Schuster editor. Sounds obvious enough, right? But their plot could easily have led them down a wayward path, toward a public-service-announcement packaged by a book publisher.

Instead, We Are Not Like Them has earned starred industry reviews, been picked for Good Morning America’s book club, and chosen as an Amazon editors’ pick for Best Fiction & Literature since its October release.

The novel introduces two best friends in contemporary Philadelphia: a Black news reporter, Riley, and a white, pregnant homemaker, Jen. Their friendship is put to the test when Jen’s husband, a local police officer, shoots Justin, a Black teenager, while in pursuit of a crime suspect. Riley steps in to cover the news event, putting her friendship with Jen in jeopardy — and on the news. They’ve been best friends since kindergarten, but never really talked about race before. Now they must start.

The impetus for the novel came after Pride edited Piazza’s 2018 novel, Charlotte Walsh Likes To Win, sparking a friendship between the two women. Soon after, Pride stepped away from a 20-year editing career, and the duo sold We Are Not Like Them and another co-written novel to the HarperCollins imprint William Morrow. (The deal wasn’t the first co-authoring venture for journalist Piazza, who previously collaborated on two books — The Knockoff and Fitness Junkie — with former Marie Claire Fashion Director Lucy Sykes.)

Below, Pride and Piazza talk with Bustle about faulty characters, sidestepping stereotypes, and book two.

“Why do they think they’re such good friends if they’re not talking about race?”

Let’s talk a little about the writing process. Christine, you’ve collaborated with Jo before, but don’t normally work on this side of the writing process. How was this experience different?

Christine Pride: I’ve been an editor for 20 years, so it’s very surreal to be on this side of things. There are strict roles when you’re an editor and a writer. It’s ultimately the writer’s name on the book, so whatever suggestions I might make, they are very much take-them-or-leave them. I’m just trying to help make a better book. But when you’re collaborating with somebody, it’s very much 50/50 in terms of ideas and writing, so the dynamic is different.

Can you tell me about a moment when you disagreed when writing?

CP: It’s so funny because we talk so much about how fraught this process was, especially early on, in terms of the learning curve, trying to figure out how to work together, and the race stuff, when that came up. It’s interesting to look back on now. Jo is very idea-oriented. She is very radical sometimes, in a good way, in terms of let’s try this, let’s try this, let’s try this. She would text or call with ideas that would not work mechanically or structurally sometimes.

Jo Piazza: Oh, Riley had a Tuscan study abroad year at one point, remember? We took that out.

CP: I do remember that. Sometimes I felt like [I was] pooh-poohing all the big pie-in-the-sky ideas. But I think that balance is important. That grounded our overall creative approach throughout the entire book.

In your Good Morning America interview, you talked about tough conversations between the two of you during the writing process. Can you tell me a bit more about those conversations?

JP: In the beginning, I thought Riley and her family were too perfect, that they would be unbelievable on the page. I was like, “This has nothing to do with race, but we have to give them some flaws. They can’t be perfect. I would do this to a white family on the page, I would do this to a Latina family.” I didn’t see it as having to do with race, I saw it as having to do with writing a character who people would be interested in because people are interested in complicated human beings.

Christine countered by saying, “There are a lot of stereotypes and clichés I don’t want to put on Riley and her family, because they’re constantly put on Black families,” and I had to humble myself.

CP: One of the blind spots I had is that I grew up having really close interracial friendships, [but] my personal experiences have been rare. Most people do not have close intimate relationships with different kinds of people. I also have had detailed talks about race with my white friends, so one of the tensions for me in this book is, even as we were writing it, I was like how are [Riley and Jen] going to be really good friends if they’re not talking about race? Why do they think they’re such good friends if they’re not talking about race?

Has anything surprised you about the public reaction to the book?

CP: I was surprised at the number of people not talking about race in interracial relationships. [Readers] seemed grateful to have the book as a launching point for some of these conversations, which is gratifying because that was the whole point of the book to begin with. We wanted to write a compelling story, but we also wanted it to be a book that brought people together. So it’s gratifying that’s happening, but also still surprising the degree to which we need something like that in our society.

JP: What surprised me the most, I think, [are the] strange conspiracy theories around the book. Like that [the book] must’ve been written by a white author and they must’ve just tacked on a Black author to make it OK to publish. It takes agency away from Christine. This book was her idea, and she came to me with it.

CP: I’m going to disagree with Jo on just that last point a little bit. I don’t want to overblow this conspiracy theory. This is one woman on the internet. [The theory] doesn’t bother me because it’s right for Black people to have skepticism about all-white industries, right? I actually don’t think it’s crazy to think a publisher somewhere would do something like this.

JP: I was more upset on Christine’s behalf, because I know how hard she works. Taking that agency away from her, I felt very upset about.

CP: Which I think is interesting, because I was not upset at all. As a Black woman, you can’t be upset when other people are skeptical in the same way you would be skeptical.

Can you talk a little bit about the climate of police brutality when you started writing the book versus today?

CP: I don’t think it’s that different, to be honest. Post-George Floyd[’s murder], and with the Derek Chauvin verdict, I think there was a feeling things had changed. But one verdict does not a pattern change. That was an important verdict. We needed that as a society. Yet one verdict also doesn’t overhaul the systems in place and the culture of police forces in places. That is not a change that’s going to happen overnight. We can all be hopeful, [but] it’s too soon to say that there [have been] material differences, both in terms of policing itself and in terms of conviction and indictments for officer-involved shootings.

You did a lot of reporting before writing the book, including interviewing news anchors and police officers. Did anything surprise you?

JP: I mean, there were some officers who declined to speak to us. But the officers who chose to sit down and talk to a white woman and a Black woman, knowing what we were writing, are self-selecting.

CP: That’s true. And I think people, both police officers and the public at large, had preconceived notions about what our agenda was. That’s just the world we live in. We weren’t writing about an issue, period. We’re writing about characters, a friendship, loyalty, motivations, regret, choices, dreams, et cetera. We’re hoping the positive reception from so many different corners helps anybody who’s making a knee-jerk assessment.

Were you drawing on previous contacts or were these mostly cold calls?

JP: Both.

CP: And personal networks. My brother-in-law is really shy, but [his] brother is a police officer in Baltimore. You say “interviews,” [but] some of them were like conversations at the dinner table.

JP: There’s a big police wife network on Instagram, and when we found women who we thought might be interesting [to] interview, we just cold DM’ed them, [like] “Hey, we’re a Black lady and a white lady writing a book.”

CP: We did it along racial lines, truly.

JP: Because we thought it would be more effective. I think it probably was. So if we were reaching out to a white officer or a white police wife, I would be the first point of contact. Christine did the same when we were reaching out to Black officers or other Black individuals. We made a conscious decision to do that. We were nervous about our emails seeming racially charged if it was the other way.

Was there anything different about the way you approached the mothers of shooting victims in particular?

JP: Yeah. Covering a mother’s grief, reporting on a mother’s grief — it is something you have to be so incredibly sensitive to. It’s a series of interviews. You don’t just show up once and ask a bunch of questions. It’s unfair to take something from a community without giving back your time. I’m still in touch with many of those mothers now.

CP: It’s interesting that so much of the making of the book is mirrored in the book. [Riley’s] a reporter. She wants to get the story right. She deeply cares about the people she’s “covering,” but there is a complicated factor there. That’s a balance we also experienced. We wanted to tell an authentic story. We wanted to talk to people about it to make sure that it was right and fair and balanced and rich and would make them proud. But at the same time, it’s them giving something to us, and so we had to be delicate about that.

What’s next for the two of you?

JP: Right now, we’re 100 pages into book two, which will be [about] different characters but also exploring race in intimate spaces. We’ve seen a real hunger for this from readers.

Will readers see familiar faces from the first book in the second book?

CP: No, as of now. Never say never — we’re 100 pages in. Jo might have a radical idea that Riley moves to the town that we’re setting the book in.

JP: I like Easter eggs. That’s all I’m going to say.

CP: But right now it’s a different universe and a different set of characters.

JP: I just had an idea. I’ll tell you later.

CP: Can’t wait.

JP: I think you’ll like it.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.