Books

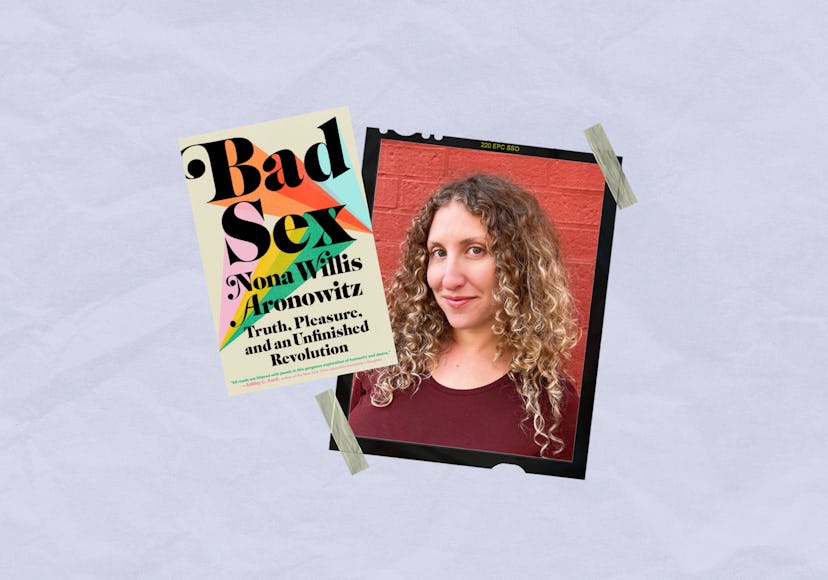

We’ve All Had Bad Sex. Nona Willis Aronowitz Is Talking About It.

Willis Aronowitz’s new book, Bad Sex, reckons with the gap between our ideologies and our desires.

The title of Nona Willis Aronowitz’s new book — Bad Sex —is enticing in itself. Good sex certainly looms larger in our fantasies and conversations; the vast majority of sex talk these days is filled with the pressure of pleasure-seeking, the thrill of desire, the right to orgasm. But there’s something more alluring — even taboo — about discussing its counterpart (though, despite a lack of data, I have to imagine that bad sex is a whole lot more common). We might see glimpses when our friends complain about a hookup, or when we read an anonymous advice column or Reddit thread; we might make assumptions, and imagine that long-married couples are uniformly having bad sex (myth!). Usually, though, that’s as close as we can get.

Willis Aronowitz, a writer, editor, and Teen Vogue relationships columnist, is here to talk about it all: the good, the bad, and the political. (The latter is particularly sticky; as she writes, “no ideology, not even a feminist one, can deliver the key to my deepest desires.”) In Bad Sex, Willis Aronowitz admits to her own foibles and failures, but also celebrates her titillations and triumphs. She dives deep into the historical responses to bad sex and bad relationships and bad marriages, even looking to her own parents, activists Ellen Willis and Stanley Aronowitz, and analyzing their marriage alongside their writing. She also investigates her first stab at matrimony, which ended in no small part due to bad sex. Nowadays, Willis Aronowitz says, she’s found her way to a much more satisfying, if still inevitably politicized, sex life. If ideology can’t to save us from bad sex, chasing our desires, it seems, really can.

Below, Willis Aronowitz discusses what her own experience with bad sex taught her about relationships and sexuality.

Why do you think we're having bad sex?

I don't think we're having worse sex than any other period in history. What I do think is that our expectations are higher than ever and our sex is stubbornly not keeping up with those expectations. Michelle Goldberg actually put it really well in The New York Times — she said something like, this is “what you get when you liberate sex without liberating women.” I think that for decades, sex has become more and more accepted and ubiquitous — you can have premarital sex now and it's fine, and you can have all kinds of different sex now and it's fine — and yet we still live in a patriarchal society. Misogyny is still rampant. And these questions that women have been asking for decades have still not been answered, but there's this expectation that they have been answered. So I think the letdown is more intense.

Why do you think we’re afraid to talk about the fact that we’re having bad sex?

I think it's precisely this perception that we have all the tools in our toolbox to have good sex that makes [bad sex] so hard to talk about. I felt like I grew up in an era where all the information and resources I could possibly want to have good sex were at my fingertips, and yet I wasn’t somehow having good sex in this relationship that was supposed to be progressive and modern and completely voluntary. I wasn’t financially dependent on my ex husband; I was a sexy modern woman who deserved to have good sex and multiple orgasms and I felt I was kind of failing to do that. I felt like people would judge me for staying in a relationship that was unsatisfying sexually, for not living up to that expectation. When things weren’t going well in my sex life, I felt loathe to admit it to people who thought of me as a sexually liberated feminist. (I don’t know if they’d use those words, but people who thought of me as a horny, confident woman.) Ironically, we’re living in this era with high expectations for sex, but it’s making it hard to talk about the things that early feminism was supposed to make it easier to talk about.

Your parents were very political, and your mother in particular wrote and spoke a lot about the politics of sex, so in a way this book is a continuation and examination of their work. What was it like to write about your parents and sex?

I knew I wanted to flesh them out as humans rather than just my parents, but I didn’t know what I was going to find. I learned the circumstances of my mother's abortion; I learned all kinds of painful stuff about my dad's affair and how she felt about it. I mean, it was kind of gross to think about their sex life on one level, but on another level, it really shaded in some contours that you don't often get to shade in with your parents. It was really a gift not only to this book, but to getting to know them.

This is not exactly about sex, per se, but it's about sexual politics. I just had a baby a few months ago, and neither of my parents are alive to see it. I've been really intensely wishing I could talk to my mom about a lot of things, but particularly about the negotiation with my father about being equal co-parents. I've found that all the biological stuff that's going on, all the hormonal stuff that's going on for me is really conflicting with my idea of equal parenting. I just really, really wish I could ask my mother how she dealt with that. I know my parents talked about equal division of childcare, and as far as I know, it was split 50/50. But now that I see how hard it is to be the birthing parent and the breastfeeder and everything, I really want to ask her how she negotiated that on a political level. I thought it was gonna be super unsentimental about breastfeeding. I thought, I'll just give her formula so that it's as equal as humanly possible. But my instinct has clashed with that, and it's been really hard to grapple with, to be honest.

That's also a huge theme of the book— that often our instinct or desire clashes with the political belief that you align with.

I think it's impossible to separate the political and the personal, especially when it comes to sexuality, which is so weird and subconscious and constantly changing. It's impossible to align them completely. You can have a very clear sense of what you want politically in a relationship, in bed, in a marriage, but then when you're there, your gut feelings get in the way — and even though these gut feelings might be socially constructed, that doesn't make them feel any less real. Jealousy is a perfect example! There’s no way jealousy isn’t socially constructed, but it’s also one of the most visceral emotions; it's awful and anybody who's felt it knows what I'm saying. It rocks your whole body, it makes you hyperventilate, you feel it very physically. But jealousy is also wrapped up in all kinds of culturally-prescribed ideas of pride and respect and exclusivity or hierarchy. It’s impossible to be like “these are my politics and I’m never gonna feel a certain way.” You never know how you're going to feel when it comes to sex and love.

So how do we have good sex?

I think no matter how strong of an activist you are, you have to remember that you were socialized in the past, you live in the present, and your work is trying to change the future. So you can't have the standards of the future when you're dealing with your immediate personal life. You have to have a bit of self-forgiveness and remind yourself that you came of age decades ago. So I think step one is just to acknowledge that, and forgive yourself and accept yourself for having somewhat incongruous personal feelings. And then think very actively about your desires. I think with many cis heterosexual people, they are sort of living in this world where that is seen as the default and they don't think a lot about why they're heterosexual or what they like about being heterosexual. They do plenty of complaining about heterosexuality, but they don't kind of affirmatively choose this life, which was a real revelation to me, to really think actively about what it is that I loved about men and lusted over.

You’re explicit about the fact that bad sex played a part in ending your previous marriage. Is there room for bad sex in a relationship from time to time? What do you think people should do when they have bad sex in their primary relationships?

So this is a really important question, and I am worried that people are going to interpret this book as: if you're having bad sex in your marriage, you must leave the person. That's really simplistic; I don't agree with that. There can be really fulfilling relationships that where sex is on the back-burner or even completely absent. Ask anybody who's asexual, ask anyone with chronic illness that makes sex really hard, ask anyone who, for whatever reason, can't or doesn't want to have sex in their primary relationship. In my case, I was very badly wanting good sex in my primary relationship. And it wasn't there, and that wasn’t changing. I’m in a new relationship and I’ve [been living] in a pandemic, and pregnant and postpartum, and all three of those things have totally f*cked with my sex drive in weird ways. I can say that sex is not constantly the most important thing in a relationship. But at that time, I'd been craving sexual connection with my primary partner and not getting it. If that relationship had been extremely strong in all the other ways except for sex, we might have been able to work something out, but that was the gateway for me realizing that other types of connections were off, too.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

This article was originally published on