28

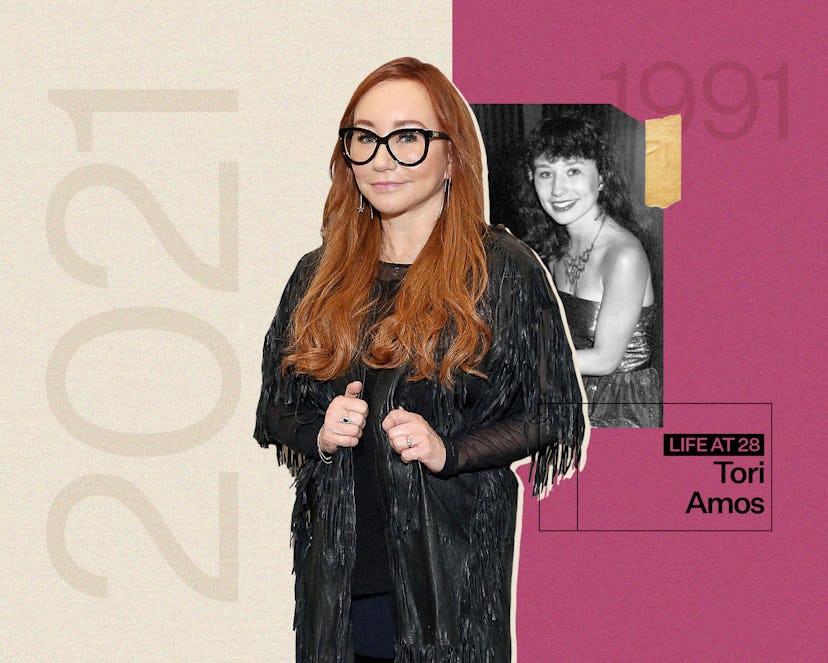

At 28, Tori Amos Found Her Voice

In 1991, the singer released “Me and a Gun,” a searing ballad about sexual assault.

In 1988, Tori Amos made a promise to the muses: Help me write this music, and I promise I will always be honest in my lyrics, always use my art for good. At that point in her career, things were not exactly off to a raucous start. Her synth-pop project, Y Kant Tori Read, had just bombed, and her debut album had been rejected by her record company. Amos had once been the youngest person accepted to Johns Hopkins University Peabody Institute at 5 years old, but after a decade of playing in piano bars, she was wondering if she’d ever fulfill the promise of her early success. Thankfully, the muses came through, and in 1992, a 28-year-old Amos released her extremely successful debut album, Little Earthquakes. Immediately, it cemented Amos’ place in the pantheon of greats.

It wasn’t your standard singer-songwriter fare. Little Earthquakes was radically vulnerable, filled with reflections on Amos’ religious upbringing, sexual experiences, and innermost vulnerabilities; the lead single, “Me and a Gun,” detailed her rape. Amos wasn’t sure how it would be received. “I didn't know how people would respond because the piano was not cool at that time,” the 58-year-old singer tells Bustle. “But people started coming up to me after the shows, they would line up and talk to me about their experiences and how this record reflected what they had been through. It was as if I hadn’t realized just how many people had gone through trauma in their life.”

Sixteen studio albums later, Amos continues to give people permission to feel and talk about their trauma, both as a musician and as the first national spokesperson for RAINN (Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network). She’s never been afraid to write about what scares her most. The candor goes hand in hand with her searing voice, which sounds like a mash-up of Kate Bush and Siouxsie Sioux, if they were screaming into an ancient cave. When you hear Amos sing — particularly on her famed Live at Montreux album, recorded in 1991 and 1992 — it feels otherworldly, as if she rose from the sea one day, shook the salt off her bright red hair, and sat down at a piano.

With her most recent album, Ocean to Ocean, Amos takes on grief. In the wake of losing her mother and weathering multiple lockdowns in Cornwall, England, with her family, she’s found solace in nature. “It is hard to define grief and hard to know when grief is going to hit you, even if you think you’ve dealt with grief,” Amos says. “I lost my own mother and not being able to call her, I turned to Earth mother, who said, ‘Bring your tears to me, let's shift this and see the magic around you.’” That magic can be heard on the album, which summons something mystical and sublime. Maybe it’s the muses.

Below, Amos discusses the start of her solo career, the stamina required to play in piano bars, and what she’d tell her 28-year-old self.

What was your life like at 28, in 1991?

In 1991, I had a single come out, a little EP with “Me and a Gun” and “Silent All These Years.” After having just seen Anita Hill on television say “I could not keep silent” — that was on October 11, 1991, and then “Silent All These Years” came out soon after that. [I had] no idea she was going to say that [testifying against Clarence Thomas]. She had great courage to speak up and speak out, and I think that was a real testament of the time — almost an underscoring of what was to come, with women finding their voice over the next year, and years, really.

Little Earthquakes was such an intimate debut album, covering everything from your childhood to your violent assault. How did it feel to bear your soul at 28?

Well, I didn’t know what was coming. I don't think anything can prepare you for it, because honestly, I had no idea that there was going to be a response. I wasn’t thought of as a commercial-type artist; I wasn’t a pop princess. I didn’t know what to expect. I just knew I had to play these songs because it was what I had been through. I was shocked, I was totally shocked that people would come stand in line. [That] they would buy a ticket to hear my songs after playing piano bars since I was 13 years old where people would spill beer all over the piano and me, playing everybody else's songs. It was quite something that people would actually pay to get a ticket and come hear my own songs.

What was the process of making Little Earthquakes like?

The record was written in different stages because it was rejected when I first turned it in. I needed to go add some songs to it, so we took a road trip. We were in California and we went to the Southwest and we went up to Colorado and came back through Utah. Songs like “Precious Things” were inspired by that trip. I guess I have been applying that idea over the years, which is to take a pilgrimage, to go to a different place to get inspiration to break your routine. We would do that we would go to the desert and do that and come back. I’ve been doing that ever since really, trying to take a pilgrimage.

I hear so much that writing is all about routine, about waking up and sitting at your desk every day. But that doesn’t seem like your process at all.

Yeah, I don’t do that. I have total respect for people that do that, [but] my thing is researching, intake, taking in thoughts, stories, documentaries, reading books, and even hearing music — especially music someone will play me that I haven't heard before. There is a point when the muses arrive, and I cannot tell you when that is going to be, and that drives everyone insane. If I am on a deadline, especially, I think, “Okay, can’t you just show up? Björk’s fine, leave her back in frickin’ Iceland, she is absolutely fine without you, where are you anyway?” (I say that with an absolute affinity for Björk.) I can’t tell you when they are going to show up but I know when they are not here, because the music doesn't have the same ... it’s not the same. So I can sit there and put some tunes together, but it is not the same thing as when the muses pop in. It has been happening forever, since I was little. When they don't show up, I get a little anxious, especially if it's been a little while.

After it came out, Little Earthquakes charted quickly and then you immediately embarked on a world tour. How did you take care of yourself and adjust to life on the road?

I had played at a piano bar for so long, it helped give me stamina in order to do these shows, three on, one off, six shows a week. I guess I was in the peak of my physicality at that time, but I had worked up to it for many years. My mom came out on the road with me and she would hang out with me and visit, and it was such a fun exchange that we had. I treasured that.

Do you have any vivid piano bar memories?

God, there were so many I’ve tried to forget. Oh my goodness gracious. Look, there is always that time of night when somebody would want to grab the microphone. That is going to happen around 10:30 p.m., when you have somebody that has probably been drinking since happy hour, bless them, and they start to change the lyrics to songs. I won’t get graphic because it will make you cringe and I just don't want to do that — I guess you call it karaoke now, but it’s kind of drunk karaoke and changing the words. Those were the times of the night you had to keep your sense of humor and just keep playing even if the beer spilled on you and smile and get through it. The bartender would usually be there nodding with you.

Is there any advice you wish you could give your 28-year-old self?

“You really need to get a better sense of direction, Tori.” I would always end up on the wrong side of the stage. I would run into a wall and then I would just pretend nobody could see me but, of course, my shoes would be peeking out from under the curtains so everybody knew I was there. I didn't know where I was going half the time; people were trying to tell me, but I just did not have a sense of direction. I would tell me to get a compass.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.