Life

Here’s What Happened When My Mom Hid Her Cancer Diagnosis From Her Family

There’s a scene about halfway through Lulu Wang’s 2019 movie The Farewell, out in July, where Billi (Crazy Rich Asians breakout star Awkwafina) is discussing the ethics of keeping her Nai Nai, her grandmother, from knowing about her own cancer diagnosis. As Billi and her family argue in the waiting room about whether it’s the right thing to do, Nai Nai’s sister speaks up: It isn’t wrong, she says, and she wouldn’t be upset because Nai Nai herself kept her husband from knowing about his own cancer.

At this point, most of the audience members at the Sundance screening I attended laughed, shaking me out of the trance I had been in. Who would keep something so serious, like cancer, such a secret, people around me asked.

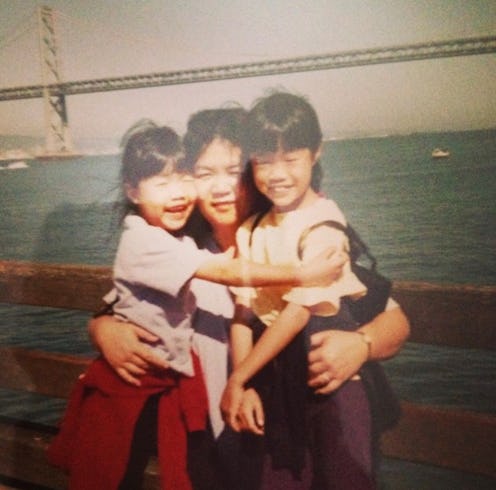

A few years ago, I might’ve asked the same question. Two years after losing one of her sisters to kidney cancer — a diagnosis she was desperate to keep quiet, until it was too late — my mom was diagnosed with breast cancer in March 2018. One of her first requests to my sister and me when she told us: please don’t say anything to anyone until I’m better. That included family.

The Farewell, which made its debut this year at Sundance, is based off of director Wang’s own experiences, and therefore already not impossible to envision playing out in real life. In fact, a study of 124 families published in 2018 in the journal Cancer Management and Research found that the practice of not informing a patient of their own diagnosis was common in China, with less than half of cancer patients knowing their diagnosis before chemotherapy.

In The Farewell, Billi, a young Chinese-American woman, goes to China to be with the rest of her family while they throw an impromptu wedding as an excuse for everyone to see their grandmother — who has not been told about her stage 4 lung cancer — one last time. The family’s decision to not tell Nai Nai of her diagnosis becomes a point of contention between Billi and the rest of her family, who do everything they can (including doctoring test results) to keep it a secret from the family’s matriarch.

Although I wasn’t keeping my mom from learning about her cancer, I still identified with Billi’s struggle to hide a life-altering diagnosis. Being down in Los Angeles while my parents were up in Sacramento made every step of the cancer journey harder. I had to hear medical updates from afar, but also had to lie to the family around us who wondered why my mom wasn’t visiting her daughters on a regular basis anymore. Every trip my sister and I made up to Sacramento for her chemo sessions was a secret, which was challenging when it meant missing family gatherings in LA.

“The word ‘cancer’ is a death sentence to people like your po-po,” she would say about my grandmother, who was still hurting from the loss of one daughter to kidney cancer.

My Chinese American friends were always quick to point out how deeply ingrained in our culture it was to “not be a burden” to others. It was the same reasoning that led my aunt to hide the severity of her kidney cancer until the doctors saw little to no hope.

Should we send out messages to family members now, just in case this was the end?

But my mom couldn’t hide her illness for that long. The first time I knew my grandmother was suspicious about the cancer was when she pulled me aside after dim sum and asked pointedly in Cantonese: “Where is your mother?” I stumbled over my words in Chinglish, trying to speak quickly so she couldn’t understand everything I was saying. “She’s busy,” I stammered. “She’ll visit later.”

We held onto the concept of “later” for a long time. She’d visit later, when she was better, meaning she’d get better soon. After all, the doctor said she was lucky: The cancer was just barely stage 2. A few months of chemo, followed by surgery and a few months of radiation, would make it disappear. Mom is relatively young — 61 when she was diagnosed — and healthy. The biggest thing she worried about was leaving daily chores to my dad, who rarely made grocery store trips or cooked before he retired.

With each hospital visit, she grew more tired and her hair fell out, but there was an obvious light at the end of the tunnel. “The doctor is upbeat about it,” Mom would say after each appointment. She was upbeat too.

Then, one day in July, Mom got really sick. By the time my parents got to the emergency room, her hemoglobin count — a measurement of the protein in red blood cells that carries oxygen throughout the body — was 3.1 g/dl, 9 grams below what was considered average for a woman. The doctors ordered blood transfusions and tests, but found nothing to explain why she was suddenly on her deathbed.

We packed my sister’s car and raced home. The entire drive up, I kept wondering what would happen if she died. Should we send out messages to family members now, just in case this was the end, and incur my mom’s wrath later if she turned out to be OK? How would we explain this to family members who were still heartbroken from losing my aunt in 2016? And if we didn’t say anything, would my grandmother ever forgive us for not giving her the chance to say goodbye?

When we arrived in Sacramento, she was out of the ICU but still in the hospital, awake and eager to go home. Because the doctors couldn’t find the source of any bleeding, they waited until transfusions raised her hemoglobin count and sent her home. Less than 24 hours later, Mom nearly fainted between the kitchen and the living room, and then she was back in the ICU. Each day, we’d visit; each night, we’d reluctantly leave.

The night before my sister and I went back to LA, I walked into her room to see her carefully arranging her things on a nightstand. I wanted to tell her everything I was feeling — the paralyzing fear of living in a world where cancer could rob me of a parent — but we don’t do that in my family.

“Maybe you should think about telling po-po now,” I said.

She shook her head. “I’ll be home soon. I’ll be fine,” she responded. Her voice was shaky.

In that moment, I heard the depths of how terrified she was, despite how upbeat she had been at the start. I realized that maybe not telling our family about the cancer wasn’t just her way of trying not to “burden” them. Maybe it was a way for her to protect herself. If she didn’t have to tell our family, then maybe it wouldn’t be “real.”

I might not agree with it, but I understand now why she did it.

I thought back to some of the times I kept things from my parents until after the fact — not because I didn’t want to worry them, but because I was trying not to worry myself: the time I failed my linguistics course in college (twice), the time I ran out of money while interning in D.C., the time I decided to move back to California after five years in New York. Each time, I waited until the situations were over or fixed before I told my parents what my plans were. Each time, there was usually a pause and then a sigh as they accepted whatever I had decided.

It’s been six months since Mom’s surgery. She’s finished radiation, and we can say that she’s officially cancer-free. Once her oncologist gave her the good news, she came to LA and told the rest of the family. Her cancer is something we only talk about in passing now, as if it was an episode of a TV show we’re finally all caught up on.

I don’t argue with her anymore about why she kept the cancer from our family for so long. Ultimately, the decision was about how much she could allow herself to feel. I might not agree with it, but I understand now why she did it. All the rest of us could do was hope for the best.

This article was originally published on