Books

This Chicana Author Is Writing Love Letters To The Women Of Her Homeland

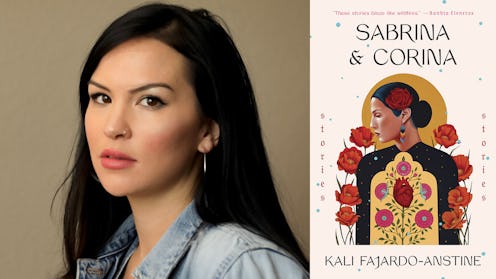

When Kali Fajardo-Anstine learned that Julia Alvarez had endorsed her debut short story collection, Sabrina & Corina, her knees buckled. A few days later, when she discovered that Sandra Cisneros had also praised the book, she wept.

"I always was a reader, but it wasn’t until I started reading Julia Alvarez and Sandra Cisneros in high school that I really felt like it was possible for someone like me to become an author," Fajardo-Anstine tells me. "I loved literature, but it didn’t seem like literature was a space that was welcoming to me, a Chicana from the Southwest who is mixed."

In the 11 stories of Sabrina & Corina, Fajardo-Anstine writes a love letter to the Chicanas of her homeland — women as unbreakable as the mountains that run through Colorado and as resilient as the arid deserts that surround it.

Fajardo-Anstine grew up in Denver, a city where more than 30% of the population identifies as Hispanic, Latinx, or American Indian. In recent years, many people in these diverse communities have become victims of Denver's rapid growth. The city now boasts one of the nation's lowest unemployment rates, but it also leads the U.S. in displacement of Latinx communities due to gentrification, a hurt that pumps through the arteries of this collection. In the final story of the collection, "Ghost Sickness," Fajardo-Anstine writes of a young woman attending college on a scholarship awarded to the children and grandchildren of those who were displaced from their homes in order to build the university. The scholarship is based on one that actually exists at the University of Colorado, Denver, a stark reminder of the forced sacrifices made in the name of the progress, and the well-meaning but often inadequate attempts to amend generational wounds.

The rapid gentrification of her hometown is one of the factors that pushed her to tell the stories of the women who cannot easily trace their roots to any place besides the Southwest, women whose families have always called Denver and its surrounding areas their home.

Like many Chicanas, Fajardo-Anstine isn't a first generation immigrant, or even a second generation immigrant. Her family has lived in the United States for centuries — "The border moved over my ancestors," she tells me — which is why she chose not to write about the immigrant experience in her collection.

"I studied Chicano studies as a minor in college, and I was exposed to all this literature about the Latinx experience," says Fajardo-Anstine, who received her B.A. from Metropolitan State University of Denver and her MFA from The University of Wyoming. "But over and over again, I was reading about the recent immigration experience," she tells me. "It’s incredibly important, and I needed those works. But at the same time, I don’t see myself, I don’t see my family in those works. I just wanted us to have a book."

"I would hear from professors, 'Can you make this more Mexican? Why aren’t these characters speaking Spanish? Like, can you talk more about the food?' Just things that aren’t really integral to my story."

In pursuit of writing her truth, Fajardo-Anstine encountered obstacles that many Latinx readers will instantly recognize: The feeling of not being enough of one's culture, and of being pushed to act in a way that felt inauthentic to her actual experience.

"Early on in my writing career — I mean like workshops and classroom space — I would hear from professors, 'Can you make this more Mexican? Why aren’t these characters speaking Spanish? Like, can you talk more about the food?' Just things that aren’t really integral to my story. And so, I was being pushed in this direction where my work didn’t seem brown enough. It felt sort of white. And then there was the complication of the fact that my characters come from the pueblos, so they’re indigenous, too."

Fajardo-Anstine doesn't speak Spanish fluently, and the book is written entirely in English. In one of the stories — "Sisters," set in the 1950s — she provides text markers to indicate when the characters are speaking Spanish (at home, usually) and when they're speaking English (in public, always).

"I think our ancestors were shamed for speaking Spanish, and now I feel shame for not speaking Spanish," Fajardo-Anstine tells me. "I want to learn Spanish, but I also want to get to a point where I’m not embarrassed by the fact that I’m monolingual."

A Pew Research Center study from 2015 found that while 97% of Latinx immigrant parents speak Spanish to their children, the rate drops dramatically among second-generation parents to 71%, and to less than 50% among third or higher generation parents. While 88% of Latinx people in the United States believe it's important that future generations speak Spanish, 71% also believe a person does not need to speak Spanish to be considered Latinx. The message of the data is clear: The longer a Latinx family lives in the United States, the less likely it is that new generations will learn to speak Spanish at home, and that can provoke an identity crisis about whether or not one actually qualifies as being really Latinx if one can't easily trace their roots to a Latin American country, or if one cannot speak Spanish or an indigenous language.

"I just wanted to be able to write in a way that felt natural to me."

"So much of Latinx literature in the past is based on this idea that there needs to be Spanish on the page, there needs to be — I keep using this word — performance of the culture, and I really want to reject that," she says. "I used to put in more Spanish, but then I had to ask my friends who were fluent if it was correct. I just wanted to be able to write in a way that felt natural to me."

The messiness of being too much yet not enough bleeds through this collection, not only as it applies to language but also to other markers of cultural identity. In "Remedies," the first story in the collection that she wrote, Fajardo-Anstine introduces readers to the traditional "remedios" passed down through generations of Chicano families. The characters of this story don't always use them, even though they know they work — and, in the end, they're the only thing that can cure their ailment. "I can cure head lice, stomach cramps, and bad breath with the right herbs," the narrator says. "For the most part, I stick to over-the-counter remedies. They are cleaner and work faster and come in packages with childproof lids. But every once in a while, when I get a real bad headache and the aspirin isn't cutting it, I take slices of potatoes and hold them to my temples, hoping the bad will seep out of me."

"'Remedies' was the first time that I took those [Latinx cultural] elements and then broke away into a different type of story," Fajardo-Anstine tells me. "'Remedies' was when I discovered what I sounded like, when I got away from the influences. You never get away from the influences, but I got away from the pressure to perform my identity rather than present it as a lived experience."

The story acts in conversation with one from later in the collection, "All Her Names," about a woman named Alicia who seeks an abortion concoction from a local botánica. (In this case, the natural remedies act as a "purge," Fajardo-Anstine says.) Years before the events of the story, Alicia endured a painful abortion using an abortion pill prescribed to her by a clinic doctor. Her abuela tells her, "Before all this bullshit, we only had the herbs, mija. Why didn't you ask me?" In both stories, the natural remedies are the second, not first, choice for these women, a particular narrative choice that speaks to the nebulous space these women occupy, even in their own understanding of themselves and their culture.

All of these stories were born of Kali Fajardo-Anstine's particular sense of identity, and, more darkly, of her experiences with violence against women, particularly women of color. In "Cheesman Park," her narrator reports a sexual assault and is promptly hit on by the police detective handling her case. It's stomach-turning moment, and one that is based on a real experience of the author.

"I think that in my mind that I sort of collect these moments, where I’m like, 'I’m going to remember you said that thing to me and I’m going to put it in art one day and you’re going to be on blast,'" Fajardo-Anstine says. "People are going to know that humanity can be this ugly."

The ugliness of humanity is most evident in "Sisters," a story so violent, Fajardo-Anstine says early readers encouraged her to remove it from the collection. Based on the true story of one of the author's ancestors, the story ends in a brutal act of violence after one of the two titular sisters rebuffs the advances of a white suitor.

The backdrop of the sisters' story is the news in their community that a young Filipina woman has gone missing. Fajardo-Anstine struggled to decide on the ending of that woman's story: Would she be found alive? Would she come home? Would she be forgotten? In her research of Colorado missing persons cases, she noticed a disturbing trend.

"The amount of open cases in Colorado I found of women with Spanish surnames, it was really devastating," she says. "They would just find this body, and the case was never solved. No investigation."

"There was so much silence and shame throughout my life. I thought, 'I’m going to overflow.'"

Fajardo-Anstine noticed this trend in her own life: When a woman from her community would go missing, it barely made a blip on the news. When a white woman went missing, it was everywhere. A phrase coined by the late PBS anchor Gwen Ifill concisely labels this as "Missing White Woman Syndrome."

"There was a lot of frustration, a feeling that I wasn’t seen, that the women that I know weren’t seen," Fajardo-Anstine says.

In her fierce, bold stories, these women — and she — are seen, and heard, and made known; the collection is both a product of pain and a celebration of survival. "Even talking about this, it's hard for me. I can feel my body change," she tells me. "I think that’s why I became a writer. I had all this pain that I experienced and I had seen so much of it. No one was telling on anybody. There was so much silence and shame throughout my life. I thought, 'I’m going to overflow. If I can’t get this out some way, it’s going to come out another way.' I did it through fiction."

Despite the darkness that shadows these characters, a resiliency flows through the collection. Even in "Sisters," Fajardo-Anstine sees strength: "She’s not married to some man she doesn’t want to be married to. She’s gotten out of this thing. She survived. She did not die. And that to me is an incredible story of survival."

Like the woman on Sabrina & Corina's cover, the hearts of these characters are exposed but intact. Fajardo-Anstine's heart is there on the page, too, beating with the blood of her ancestors.

This article was originally published on