Books

Horror Experts Reveal Why You Love Scary Stories, Even When They Freak You Out

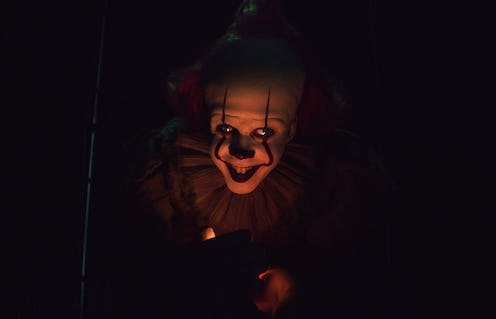

I was not a kid who loved horror. As a kid, I picked out the least scary Goosebumps books, and never, ever glanced twice at a Fear Street novel. It only took 11 minutes of the original IT miniseries to give me a fear of clowns that continues, in a somewhat reduced capacity, to this day. I only developed a deep and abiding love of scary literature after reading The Shining — and then watching the Stanley Kubrick adaptation of it, through my fingers. I still sleep with the lights on sometimes, but I'm otherwise a normal, functioning adult, in spite of it all.

As an adult, I'm a thrillseeker. I like riding extreme roller coasters and going on adventures. But still, I often wonder why we love horror, so much so that we seek it out on the page, on TV and in the theater, and even in video games. After all, fear is supposed to keep us alive, at least from an evolutionary standpoint, by making sure that we don't venture into dangerous places.

And yet, as a species, we've likely been enjoying and sharing scary stories for millennia. It's hard to imagine that the Chauvet cave paintings, which depict hordes of dangerous creatures, such as lions and mammoths, weren't accompanied by some kind of horror narrative.

"I think, probably, in prehistoric times, pretty much all horror was collective and social," Dr. Mathias Clasen, an Aarhus University professor and the author of Why Horror Seduces, tells Bustle in an interview. "It was one person telling a scary story to a bunch of other people who were listening and trembling and responding."

There is a material difference, though, in how we respond to horror on the page or in other media. Some people can't handle seeing visceral images and jump scares in a movie or video game, while others prefer them to the experience of making up a "movie" in their heads as they read a book. According to Dr. Steven Schlozman, a Harvard University professor and the author of The Zombie Autopsies: Secret Notebooks from the Apocalypse, that's because those are two very different experiences at the neurological level.

"I expect a much stronger kind of physiological arousal from a horror film."

"The studies of what your brain looks like when it’s experiencing a story told visually vs. a story told through written narrative — so reading as opposed to having it read to you — are pretty clear," Schlozman says. Although reading horror lights up the parts of the brain that deal with space and time, "When you watch a movie, those areas don’t get as engaged, in part because it’s already been done for you on the screen. So if you’re into your own kind of worldbuilding, like imagining something without it being shown to you, then you read the story. If you want to have the challenge of pattern recognition not making sense, then you watch the film."

Those qualities aren't unique to horror, of course. Dr. Andrew Tudor, an emeritus professor at the University of York, and the author of Monsters and Mad Scientists: A Cultural History of the Horror Movie, tells Bustle that, while "there’s always a material difference between reading and watching," it's not "any different, particularly, in the case of horror, than in the case of reading a novel and seeing an adaptation of that novel." What is different, however, is what horror fiction — as a genre that includes film, television, and printed works — has to offer the people who enjoy it.

Scary movies and TV shows give fans the opportunity to have a satisfyingly frightening experience in mere minutes, compared to the hours of time required to enjoy a horror novel. Clasen tells Bustle that he "expect[s] a greater kind of payoff" from a horror novel, "a more kind of rich experience of getting into the head of interesting characters."

"I don’t expect that from a 90-minute horror film," he says, "but I expect a much stronger kind of physiological arousal from a horror film."

Similarly, The Good House author Tananarive Due, a UCLA professor and the executive producer of Shudder's Horror Noire, tells Bustle that horror novels and films each have their own merits, which depend entirely on what the audience wants at a given time.

"Horror readers are really no different than any readers who just love the weight of a good book and everything that implies — the time it takes to get through it, the effort it took to write it, the pictures in their heads.... There’s just a very unique relationship that a reader has with a book," she says.

On the other hand, as Due points out, "It doesn’t take as long to watch a movie. You’re in, you’re out," and you've had a rewarding experience, if you're the type of person who loves horror movies. Horror movie marathons are more common than not, but it's nearly impossible to marathon-read novels without a long weekend — something the spooky month of October sorely lacks.

"Every day's headlines remind me why we like horror stories so much," says Due.

Whether we're reading or watching horror fiction, we need the time to experience and process it. If scary entertainment doesn't show up in the form of Halloween-season programming on TV, we have to do the work to make time in our busy lives for it. That goes double for trying times, when news is often stranger, and scarier, than fiction.

"Every day's headlines remind me why we like horror stories so much," says Due. "They’re a way to confront and engage with trauma from a safe distance."

"It’s a little counterintuitive," Due tells Bustle, "to think that if you’ve actually been through real-life traumas, that a horror movie might help you process it. But I do hear from people that that has been the case for them... It’s not for everyone, but for people who can stomach the violence and scares, I do think they can find that horror is a way to help exorcise some of those demons away."

Clasen and Schlozman warn that horror fiction can traumatize some people with anxiety, or those who can't handle the visceral nature of horror. There was some consensus, among the horror experts I interviewed, however, regarding the benefits of reading or watching horror fiction.

"Horror gives us an opportunity to play with dark emotions," Clasen says. "We learn something about how we respond to fear, anxiety, dread, and so on. And we also learn something about the world in terms of morality [and] the darker aspects of existence. And those are all things that we can confront in the safety of the movie theater or the book."

Horror, Schlozman says, is "about how we pull together, and do our best, and rise above our petty, racist or identity-borne impulses, and do what needs to be done in order to sort of get through the day, or how we let those old ways of approaching the world kind of overtake, and then we lose."

"Every horror film feels to me like it’s about that," he continues, "where you’ve got people who are like, 'No way, man, I would not sit next to you!' And you’re thinking, 'Are you kidding me? There’s a guy out there with a chainsaw. You’re going to sit next to him, and you’re going to get through this guy with the chainsaw.'"

In addition to showing us who we are as individuals, horror fiction also offers insight into who we are as a society. "Horror works as a kind of thermometer," Clasen says, "I think that’s Stephen King’s metaphor, actually. He talks about it in Danse Macabre... about how horror kind of taps into widespread sociocultural anxiety."

"You can look at the films and say, 'Ah! This is a good visualization of the social chaos of that time.'"

For a great example of what, exactly, Clasen's talking about, look at the sci-fi horror movies of the 1950s. Invasion of the Body Snatchers tapped into fears about communist influence in the U.S., while Godzilla became an outlet for postwar Japanese citizens to process their feelings about the aftereffects of nuclear war. Midcentury horror movies allowed filmmakers and audiences to sort through Cold War anxieties without having to address them directly. The problems that horror movies took on changed moving into the social upheaval of the 1960s, however.

"When you look at films like George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead back in 1968," Due explains, "and then fast forward to Jordan Peele’s Get Out in 2017, those films both clearly had their finger on the pulse of societal shifts. You can look at the films and say, 'Ah! This is a good visualization of the social chaos of that time.' So in Romero’s day, it’s the Civil Rights Era, and the anti-war era, and the fear that conservatives had that they were losing control of their country. And it’s mirrored, generations later, by the transition from President Obama to Trump, and that voicelessness and powerlessness that Black people feel and felt both under Obama and Trump is visualized on screen by these films."

Although the shared experience of watching a horror movie with your partner, or going through a haunted house with friends, can be quite beneficial — as a bonding experience and as just plain fun — The Hunger author Alma Katsu tells Bustle that the deeply personal experience of reading a horror novel allows for a different level of engagement, both with the material and with one's own self.

"It’s sort of, not only a safe space, but it’s a completely personal space," Katsu says. "It’s just you and the book. You don’t have to tell anyone else what you thought, or what your reaction was."

Horror fiction allows us to dig into conversations that aren't generally intended for so-called polite society. "Horror films actually present you with some pretty interesting questions," Schlozman tells Bustle. "You have those conversations, and you’re able to sort of hash out some things that have avoided being talked about, precisely because they’re so off-putting. Once they’re in that crazy displacement of horror, it actually becomes easier [to talk about them]."

"That was the interesting thing about writing a book that had cannibalism in it," Katsu says, "because that’s such a taboo for most people.... So it was interesting going on the road. People didn’t really want to bring up cannibalism, but occasionally, you’d get these really crazy interesting conversations about it. You know, it’s just something that you’re not often able to explore in public."

If you can handle the chills and thrills, there's no time like the present to find out what you're made of, and to pinpoint what really scares you when no one's looking.

This article was originally published on