When A Black Teenager Killed Her Rapist, Kenosha Had No Tolerance For Vigilante Justice

Will Kyle Rittenhouse receive the same treatment?

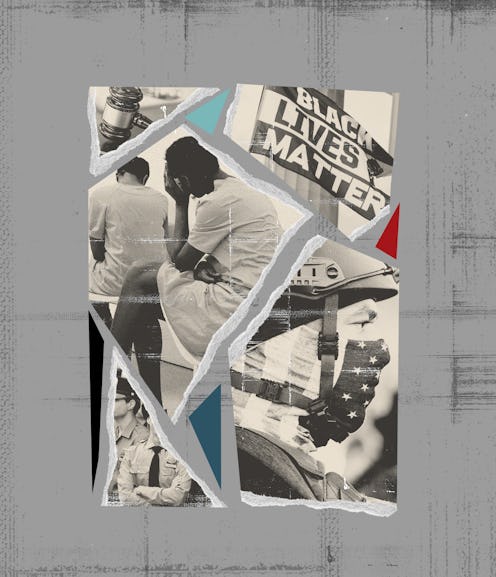

On Aug. 25, Kyle Rittenhouse, a white 17-year-old armed with an assault rifle, traveled from his home in Antioch, Illinois, to nearby Kenosha, Wisconsin, where he shot three Black Lives Matter protesters, killing two. Just two months earlier, a different teenager charged with first degree homicide in Kenosha, this one a Black girl named Chrystul Kizer, made bail after spending two years in the county jail.

Both teens say they committed these crimes in self-defense; both could face life in prison.

On June 5, 2018, Kizer shot and killed Randall Volar in his Kenosha home. She then set his body on fire, stole his car, and posted a picture of herself to Facebook with the caption “my mugshot.” Police were quick to locate and arrest her, and after initially claiming someone else had killed Volar, Kizer confessed to investigators. She told them that Volar, 34, had been raping and trafficking her out to other men for the last two years. She said that on the night of the murder, she was in fear for her life. She was 17 years old.

In her first court appearance, Kizer wore shackles and a huge, dull green anti-suicide vest that dwarfed her small frame. In Wisconsin, 17-year-olds are considered adults by the criminal court. District Attorney Michael Graveley charged her with first-degree intentional homicide. She was held in the Kenosha County Jail in lieu of $1 million bail.

“I cannot condone vigilante justice,” Graveley later wrote on his Facebook page.

What the public, as well as Kizer’s defense, didn’t know at the time was that, four months before Volar’s death, a different 15-year-old girl had called 911 to report him. She said he had been paying her for sex for about a year and that night had drugged her and threatened to kill her. In response, Kenosha police raided Volar’s home and seized computers on which he had stored hours of footage that showed him raping Kizer and other Black girls, some who appeared to be as young as 12. For reasons that remain unclear, Volar was released the same day he was arrested and charged with child enticement, using a computer to facilitate a child sex crime, and second-degree sexual assault of a child. He paid no bail but was told he’d be summoned to court. He never was.

In February 2020, Kizer’s case was turned over to the appeals court in Kenosha after a judge denied her request to use an affirmative defense — a statute designed to allow victims of sex trafficking to mitigate any crimes they may have committed while being trafficked. In February, her bail was reduced to $400,000, which, thanks to attention attracted by an extensive Washington Post article and Black Lives Matter protests, her defense was able to crowdfund in June. Kizer is at home in Milwaukee, with certain restrictions placed on her by the court, awaiting her next trial date.

Now, the Kenosha activists who raised money for Kizer’s bail are wondering how their city’s law enforcement will treat the white, male teenager accused of murder who, like Kizer, says he was in fear for his life.

The protests that brought Rittenhouse to Kenosha began on Aug. 23, after a police officer was captured on video shooting Jacob Blake, a 29-year-old Black man, seven times in the back. Two days of raw emotions, arson, and tear gas later, the “Kenosha Guard” Facebook page called for “Armed Citizens to Protect Our Lives and Property.” Rittenhouse, who appears to have idolized police officers and considered himself a militia member, heeded the call. Shortly before midnight, as protesters and police clashed, he shot and killed Joseph Rosenbaum, 36, and Anthony Huber, 26, and injured Gaige Grosskreutz, 26.

“It was only a matter of time that something like this was going to happen here, I think,” says Adelana Akindes, a 24-year-old Kenosha native, as she discusses both the police shooting of Blake and the response to protests. “I wish none of it had happened. But it’s not surprising that it happened here.” One of only two Black girls in her Kenosha high school class, she brought her knowledge of the city’s “quiet racism” to her work with the University of Wisconsin at Parkside activist group Students for a Democratic Society, including raising awareness about Kizer’s case.

When discussing Kizer’s alleged crimes, “[District Attorney] Graveley talked about vigilante justice over and over again,” says Akindes. “And he was very adamant about criminalizing her and showing her as someone that people should be afraid of when in reality she was a trafficked 17-year-old girl.” (Graveley did not reply to a request for comment from Bustle.)

In a news conference after Rittenhouse was taken into custody, Kenosha Chief of Police Daniel Miskinis seemed to place the blame for the killings on the victims, not Rittenhouse, telling reporters, “I'm not gonna make a great deal of it but the point is — the curfew's in place to protect. Had persons not been out involved in violation of that, perhaps the situation that unfolded would not have happened.”

Conservatives were quick to circle the wagons, saying Rittenhouse was acting in self-defense against a mob bent on destruction. Rittenhouse enjoyed the framing often used to describe middle-class white boys and men who have been accused of something terrible (Brock Turner, Brett Kavanaugh): His lawyers have been quoted describing him as a “fine young man,” and images of Rittenhouse scrubbing graffiti from Kenosha buildings, posing proudly as a youth police cadet in full uniform, and wearing a pair of Crocs emblazoned with the American flag circulated in conservative media. Those images are countered by video stills captured the night he killed Rosenbaum and Huber, crouched on the nighttime streets of Kenosha with his assault rifle or walking through the crowds, weapon at the ready. Still, no less than the president of the United States has come to Rittenhouse’s defense, saying he’d been “violently attacked by protesters” and that “he was trying to get away from them, I guess, it looks like.”

Black girls meanwhile, find far less empathy. They are routinely seen as older than they are, and sexualized by society at a young age. A recent study by the Georgetown Law Center on Poverty and Inequality showed that Black girls as young as 5 years old were perceived by adults to be “less innocent and more adult-like” than their white peers. This perception leads to a disproportionate treatment in law enforcement and court systems, “which may contribute to more punitive exercise of discretion by those in positions of authority, greater use of force, and harsher penalties.”

Santera Matthews, who is part of Kizer’s defense campaign and works with Survived and Punished, believes law enforcement’s apparent lack of sympathy for Kizer and other trafficked Black girls amounts to its own form of extrajudicial violence.

“This is not an anomaly,” she tells me. “Black girls are being denied personhood. The police knew about Volar’s activities. They watched the footage. But their job is to uphold white supremacy. I feel like the police are the vigilantes here.”

At Rittenhouse’s first court appearance in Illinois, he failed to appear next to his attorney when the judge ruled that her presence was enough to represent him. (The hearing was conducted via Zoom as courtrooms are currently shut down because of the COVID-19 pandemic.) His extradition hearing, which will determine if he’ll be transferred to Kenosha to await a potential trial, was delayed 30 days so his family could find a private lawyer. Nearly $1 million has been raised to help pay for his legal funds. Because Rittenhouse wasn’t present for the proceedings, unlike Kizer, there's no image of him, in a suicide vest and shackles, to accompany the first wave of articles about his legal proceedings.

On Aug. 26, as Akindes was marching to show solidarity with Blake as well as Rittenhouse’s victims, she watched as suspicious-looking unmarked vehicles drove past white men with rifles “protecting” affluent areas of the city. And then one of those vehicles stopped and told Akindes she was being arrested, for violating the 7 p.m. curfew. The men refused to identify themselves as either local police or federal officers, took her phone, and kept her in custody for 24 hours.

A lawsuit filed in federal court on behalf of Akindes and other protesters arrested that night says what many have been thinking for years: "In Kenosha, there are two sets of laws. One that applies to those who protest police brutality and racism, and another for those who support the police."