Life

I Found Out I Had Cerebral Palsy When I Was 13

One day when I was 13, my mother told me I had a disability. It was 2000, we were living in suburban Australia, and I had just ran off the school bus in order to make it home in time to catch the highlights from the Paralympic competition that day. Mom walked into the room just as the hosts finished interviewing a swimming medalist with cerebral palsy.

“That’s what you have,” Mom said, as if she might be telling me we were having lasagna for dinner. She took a seat on the couch. I turned to her slowly, then back at the TV, and squinted.

“What?”

“Cerebral palsy down your right side.” She had by now picked up a book, oblivious to the truth bomb that had dropped over me and my already angst-filled teenage life.

I waited forever for my brain to send the barrage of questions bouncing around it to my mouth, but once the cascade started, it wouldn’t stop.

Does that mean I can be a Paralympic athlete? "I don’t know. Maybe."

How come I’m not in a wheelchair? "Because you don’t need one."

Why didn’t you tell me? "Because it didn’t matter."

How did I get it? "By being a Miracle Baby."

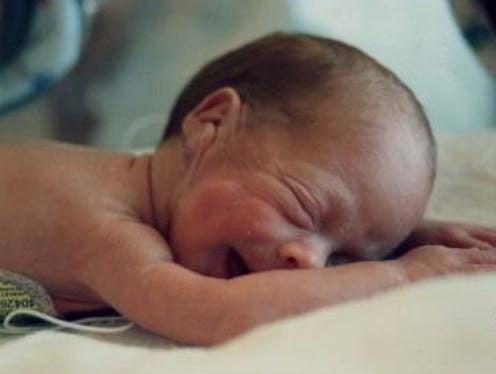

I am a Miracle Baby, which is to say that due to a very low birth weight and extreme medical complications, my very existence is well, a miracle. And my Miracle Baby story is like so many others. Born at 26 weeks and weighing a little over a pound, I was a terrifying bundle of mystery to my frightened mother, and a trigger for my father, who was already packing his bags to leave the family, never to return. Mom watched on stoically as the Miracle Baby suffered a brain hemorrhage and then blood transfusion after blood transfusion.

Back at the shared accommodation where she lived to stay close to the hospital, Mom journaled about spinal taps I underwent, the tubes everywhere, the anxious weigh ins and the constant setbacks. It was the mid '80s, after all; the survival of such a small baby wasn’t guaranteed. In one entry she wrote, “I wanted to call her Hope, but the nurse thought that wasn’t a good idea. What if she doesn’t make it?”

After three months, with her husband already long gone and a four-year-old by her side, the doctors let her take the Miracle Baby home. “Don’t expect anything. Just take her home and love her,” they said. So that is what she did.

The Miracle Baby is my mother’s story, not mine. To me, it was only folklore told sporadically through my healthy, normal childhood. The fact that I was a premature baby was at best a party trick, brought out occasionally to spice up conversation. It was a history I wasn’t present for.

My mother’s experience was one in a wave of unprecedented early labors in the 1980s that resulted in babies being born before the third trimester. Technology had finally caught up, and for the first time, medical staff had the training and tools they needed to try and keep those babies alive. Preemies were getting a shot at life that had never existed before.

Today, 15 million preterm babies are born each year around the world, many without complications.

But 13-year-old me cared about none of this, because I (suddenly) had cerebral palsy, a condition I knew nothing about outside the context of the Paralympic Games. I became obsessed with Googling my prognosis late at night and comparing myself, limb by limb, to the pictures on the screen blaring back at me. I mentally pieced together my entire young history, searching for moments when it should have been obvious that my clumsy quirks were deserving of a legitimate medical label.

I was captain of my junior basketball team, but with my newfound hindsight, I could see that position was probably awarded to me based on charismatic merit rather than physical prowess. I would stumble through five minutes of stunted dribbling before retiring, exhausted, to my seat on the bench where my arm splint lay waiting. I have early memories of toddling through doctor’s offices — one would put needles in my arm, another would massage my joints with a sticky, slick ointment that smelt like burning rubber.

My confusion lingered throughout my teens. I noticed in gym class that I couldn’t balance on my right leg like the others, and my head sat a little crooked on my neck. The boys called me "Lopsy" for a hot minute, and I joined in because it was kind of true. There was no study guide on how to suddenly be different when you’ve always thought of yourself as the same. For her part, Mom was full of one-word answers and changed subjects.

There was no coddling. She had told me what I needed to know, and now it was up to me to deal with my physical heritage however I saw fit. So I did, figuring out which doctors needed to know and which didn’t, and looking up online forums when my body became perplexing.

One morning a few years later, I came home from college for the weekend and was painting my nails on the bathroom floor. “What’s that on your foot?” Mom exclaimed, pointing down at me.

She was gesturing to the bone formation of my right foot, which was kooky and a little jagged. Functional, but funny-looking compared to its partner.

“That’s my foot. That’s just how it grew,” I offered, alarmed at her alarm.

My mother seemed shocked that my body was showing tiny signs from a time that she had worked so hard to overcome. And she had overcome it brilliantly. But she didn’t realize it wasn’t over for me; in fact, it was only beginning. Even though I survived, the circumstances of my birth were always going to affect me. “I thought if you didn’t know the obstacles were there, you would jump over them fearlessly,” she said later that night about her decision not to focus on my condition. “Back then, nobody knew what being such a small baby meant. I don’t even think they know now.”

As the first of the mass featherweight baby generation to reach adulthood, my preemie contemporaries and I are the subject of much research that will not only affect our lives, but also those 15 million new ones that come into the world every year. My mom is right — there are so many unknowns.

Researchers are conducting studies about preemies which suggest even those of us without documented disabilities may have difficulty socializing and taking risks. The earlier a baby is born, the less likely she is to get married, have her own children or earn what is regarded as a high salary.

In another study of people in their early 20s, researchers found that low birth weight babies were less likely to live outside their parent's home or be sexually active once they entered adulthood. These are preliminary studies, of course. We’re yet to see if these results will be consistent over the large and ever expanding preemie test group. But if this is determined to be the rule, then I am perhaps the living exception. I have long left my childhood home and now live half a world away with my boyfriend. Though admittedly I'm less of a risk taker than most.

As an adult now, I know my mother did the right thing for me. I am just an ordinary 20-something with an arthritic hip, a little anxiety and toes that sometimes stick together these days. Like all of us, I will continue to jump the obstacles whether I can see them or not. But my Miracle Baby story is far from over.