Books

I Decided To Tackle Rape Culture In My YA Novel

It was 2012 when the story of Steubenville High School broke. A small town in Ohio where the local football team were treated like gods. A young girl, drunk, and unconscious at a party. And we all know what happened next. The stomach turning photos and videos that were posted on social media detailed it for us in excruciating detail, and yet I, watching in horror from my bedroom in Ireland, couldn’t bring myself to look away. The entitlement these men felt to abuse her body in whatever way they wished, the jocular way in which it was treated by their peers. All those teenagers at that party, and the fact that none of them thought to object. Their lack of awareness as they documented the night on Facebook and Instagram and Twitter, seemingly oblivious that not only was what they were witnessing morally reprehensible but it was also a crime that could land them in jail.

The entitlement these men felt to abuse her body in whatever way they wished, the jocular way in which it was treated by their peers. All those teenagers at that party, and the fact that none of them thought to object.

And it wasn’t just teenagers. At least with the students at the party, one could make the argument that they were simply young and inexperienced, that they were not au fait with the ways of the world. But what of the reaction of the local community, determined to brand the victim as a troublemaker? Celebrities who said “I’m not blaming the girl but if you’re a 16 year old and you’re drunk like that, your parents should teach you: Don’t take drinks from other people.” The comments of Poppy Harlow, a reporter with CNN, who said the trial was “incredibly difficult... to watch what happened as these two young men that had such promising futures... watched as they believed their lives fell apart.” She did not express any sympathy for the victim.

Here it was, then. This was the "rape culture" that I had read about in feminist literature and had never been able to truly understand. We don’t live in a world that "promotes" rape, I would say to friends, puzzled. Everyone thinks that rape is a terrible thing.

Don’t they?

Here it was, then. This was the "rape culture" that I had read about in feminist literature and had never been able to truly understand.

"Some people deserve to be peed on," a baseball player tweeted. "They raped her quicker than Mike Tyson raped that one girl," a university student laughed into a camera. "I shoulda raped her now that everyone thinks I did," one of the men accused texted his friend.

And people watched and they laughed and they took photos and they tweeted and re-tweeted.

A few months later news of the Maryville case would break, the circumstances eerily similar. Once again, people seemed to search for any excuse they could find to isolate the victim and to protect the perpetrators, casting aspersions about the girl’s character, doubting the veracity of her story. And of course, that is rape culture. It is a culture that refuses to believe women when they say that they have been sexually assaulted. It is a culture that lends authority to the male voice over the female so when it comes down to a he said/she said (as rape cases so often do) our subconscious bias nudges us to trust that the man is rational, he is sensible. He must be telling the truth.

It doesn’t make sense, of course, but we have all been spoon-fed that same narrative by the media since we were children; that women are "hysterical" and "over emotional"; that women lie, that they "cry rape." False rape claims constitute a tiny proportion of all reports — and no more than any other crime — but are given such attention that many people think they are far more prevalent. That is why dozens of women spoke out about their rapes at the hands of Bill Cosby and were met with skepticism until Cosby himself admitted to drugging women in order to have sex with them. That is why when photos emerged of Kesha sobbing in a courtroom, her utter devastation clear to see; there are murmurs of, "Well, why did it take her ten years to leave Dr. Luke? If he had really been raping her, surely she would have left earlier?’

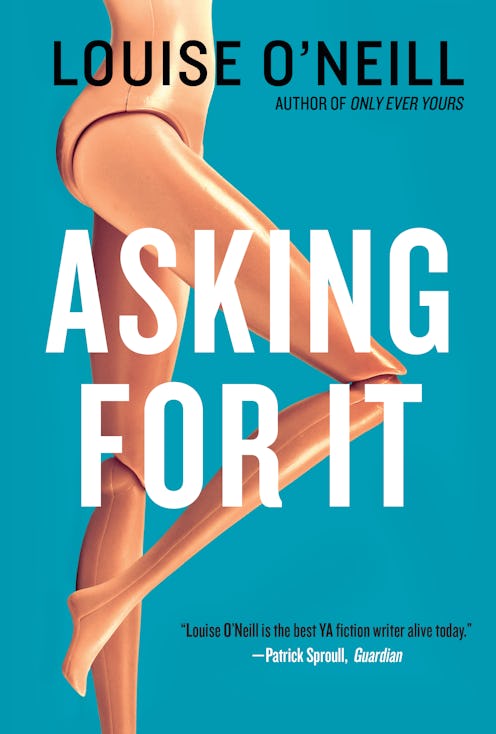

It was with all of this in mind that I decided to write my novel Asking For It . Inspired by the Steubenville case but set in a small Irish town, it was borne out of my frustration with men saying that women wouldn’t get pregnant if it was a "legitimate rape," and judges saying that teenage rape victims looked older than their chronological age, and ads for department stores that seem to advocate date rape, and feminists receiving death threats after they challenged the humor in rape "jokes." Death threats for refusing to laugh at a violation that is statistically likely to happen to one in five women.

One in Five.

I wrote my book because I was tired of looking around at my friends and my cousins and the hordes of teenage girls pouring out of my local high school and thinking “One in five.... I wonder which one of you it will be next?”

I wrote my book because I was tired of looking around at my friends and my cousins and the hordes of teenage girls pouring out of my local high school and thinking “One in five.... I wonder which one of you it will be next?”

It needs to stop. We need to make all of this stop. We need to keep talking and keep shouting at the top of our lungs. And most of all, we need to believe women. Just believe them.

Asking For It by Louise O'Neill will be available for purchase on April 5.