Life

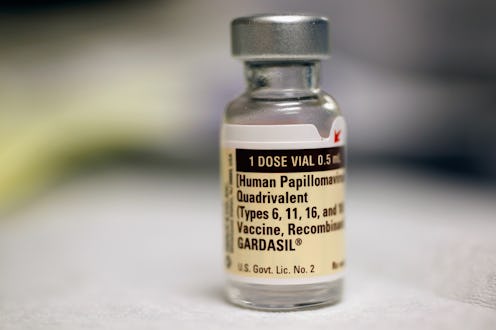

4 Things To Know About The History Of Gardasil

Today, June 8, marks the 10 year anniversary of the FDA approval of the human papilloma virus vaccine Gardasil. Today, it's such a part of the landscape that it's tough to remember how close we came to not having it at all. The New York Times reported in 2007 that the company behind marketing Gardasil, Merck, "deserves praise for developing Gardasil at a time when many companies shun the vaccine business as risky and unprofitable." If Merck hadn't decided to focus on the research of a bunch of Australian and American scientists, we'd still likely have no way to protect ourselves from HPV strains linked to cervical, vulvar, vaginal, throat and tongue. It's time for a 10 year birthday cake, and a look back at where Gardasil has taken us.

HPV vaccines, while considered safe by the World Health Organization and the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, often meet with resistance from anti-vaccine activists. In Japan, the Health Ministry initially recommended Gardasil vaccination for girls 12-16, but in 2013, it withdrew its recommendation in order to investigate what it called 186 "adverse events" that happened to people who'd had the vaccine in Japan. A few crucial things to remember, though: it wasn't a ban, and Gardasil is still available in Japan; and the Washington Post pointed out in 2015 that "there is no scientific evidence to suggest a causal link" between the adverse symptoms and the Gardasil vaccine. Outside of Japan, though, Gardasil has been a huge success. It was approved by 49 countries worldwide in the year following its debut, and is part of the World Health Association's Global Vaccine Action Plan.

So raise a glass to one of the most exciting vaccines for women and men developed in our lifetimes — and here's hoping it'll have many more decades to improve, refine, and keep protecting us from cancer.

1. The Vaccine's Discovery Was A Group Effort

The way we view vaccine development is often a bit simplistic — we typically imagine that they are the result of a brilliant scientist having a "eureka moment" in a lab late at night; but in reality, it's often the product of various teams, working independently or together, with different perspectives, resources, and ideas. That's definitely the case with both Gardasil and fellow HPV vaccine Cervarix.

The Journal of the National Cancer Institute explains that the discovery of HPV vaccines was "an incremental process with multiple contributors," which led to a number of competing patents and some argument about who could claim "discovery" rights. Everybody agrees that the first step towards developing the vaccine was taken in 1991 at the University of Queensland, Australia, when a research team led by scientists Jian Zhou and Ian Frazer discovered a way to make "virus-like particles" that could form a basis for an HPV vaccine. After that, research was done over several years concurrently by different teams across the U.S. — at the National Cancer Institute, at Georgetown University, and at the University of Rochester. All four institutions filed to patent their discoveries, and it seems to have been a bit of a mess to sort out.

2. Large-Scale Studies Have Concluded That Gardasil Is Safe

A huge part of Gardasil's history is the amount of science devoted to its safety, and you will be pleased to know that the studies declare it very safe as well as very effective. Both Gardasil and Cervarix had to go through extensive testing before they were approved for use on the wider market (the CDC records that Gardasil was tested on 29,000 people, Cervarix on 30,000, and the new Gardasil-9 on 15,000). Alongside that, though, testing has continued, with many people and in very long term studies, and the results have been hugely positive.

To name two examples, a 2012 study of nearly 200,000 young women in California who had the Gardasil injections, all between 9 and 26 years of age, showed only two significant side effects: skin infections from the injection, and fainting. And in a report published in the British Medical Journal in 2013, researchers looked at reactions to Gardasil across a whopping 1 million girls in Denmark and Sweden, and found no evidence of a link between the vaccine and "autoimmune, neurological, and venous thromboembolic adverse events" (or Bad Medical Problems relating to the immune system, brain or veins, in plain English). A study in 2014 also estimated that the HPV vaccine lasts for at least eight years in children. How awesome is that?

3. In 2011, It Was Recommended That Boys Get It, Too

Most media coverage of Gardasil and HPV in general is related to girls and women, and while that's fair (it was originally marketed as a vaccine for the prevention for cervical cancer), it's also important to remember something crucial: the vaccine is meant for boys, too. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices in the U.S. recommended back in 2011 that the HPV vaccination be given to boys at the same time as girls: at the ages of 11 or 12, before they were likely to be active sexually. HPV is estimated to cause 9,000 new cancers in men in the U.S. every year, including nearly all anal cancers, 63 percent of penile cancers and 70 percent of throat cancers. It's now on the routine immunization schedule recommended by the CDC.

4. The New 9-Strain HPV Vaccine Covers More Than The Old Vaccine, But It Still Doesn't Cover Every Strain

In 2015, Gardasil was updated to a new form: Gardasil-9. The "nine" was added to indicate the increased number of HPV viral subtypes the vaccine targeted, up from the previous four — and the sudden increase was a matter of both celebration and a bit of controversy.

As I discussed at the time, HPV viruses come in at least 100 different subtypes, and for reasons we're not entirely sure about, different subtypes seem to impact women of different racial backgrounds. Caucasian women usually contract subtypes 16, 18, 56, 39, and 66, while black women usually get 33, 35, 58, and 68. Until Gardasil-9 came out, both Gardasil and Cervavix were targeting subtypes 16 and 18, and Gardasil was also targeting 6 and 11. This led to situations like Evette Dionne's, who wrote eloquently for Bustle about getting the HPV vaccine only to discover that, as a black woman, it hadn't actually protected her at all.

Gardasil-9 represents a definite improvement: it covers subtypes 31, 33, 45, 52, 58, 6, 11, 16 and 18. But that still leaves subtypes 35, 68, 56, 39 and 66 uncovered, which leaves black women particularly vulnerable. The new vaccine is an amazing improvement that deserves fireworks and balloons, but we're still a way off from a "perfect" vaccine.

Still, we should be exceptionally grateful for the existence of Gardasil-9 and the HPV vaccines in general; according to the National Cancer Institute, the trials that led to Gardasil-9's approval gave it a whopping 97 percent effectiveness in "preventing cervical, vulvar, and vaginal disease" caused by the subtypes it targets.

Images: Getty