While there's been an interesting resurgence of the female buzzcut as of late, we can't really say this is a new look. Our past has been filled with peroxide crops, peach-fuzz cuts, and gleaming Mr. Clean-like female heads. The history of shaved heads in fashion is an interesting one, packed with many strong women who made the personal political, arguably introducing a new perception of womanhood with their lack of a ponytail.

They helped put a chink in the idea that the paradigm of female beauty is fixed, offering new definitions of femininity for the modern consciousness. Traditionally, bouncy blowouts and Godiva-like manes were what supposedly added to a woman's beauty-brownie-points. Flat tops and DIY bathroom shaves weren't usually associated with femininity at all. But that's what made those looks so exciting. The more women who rock these blunt aesthetics, the more the narrow standards of gender expression seem obsolete.

While it could be tempting to say that the female bald head is the zeitgeist of the Millennial generation, ladies have been doing it for nearly half a century, seemingly either reaching for scissors to reject mainstream norms and redefine what was accepted, or to find themselves a stronger, truer identity. Below is a history of shaved heads in fashion via seven women who made assaults on conventional beauty standards, and brought their own unique perception of womanhood into the conversation.

1. Pat Evans In The 1960s

The baby boomers in the '60s arguably protested just as much with their hair as they did with their peace signs, fighting the establishment by replacing crew-cuts and beehives with un-saloned and loose looks.

Pat Evans walked the New York streets with a shorn crop way before the look went mainstream, and the bold trim was what got her discovered while spending an afternoon in New York's Washington Square Park in 1969, according to Ben Arogundade, acclaimed author of Black Beauty.

While it was the close buzz that ignited her modeling career, she reportedly felt like she could book more shows and support her family easier if she wore a wig, folding to certain one-dimensional values of femininity in order to do so. When the wig slipped off at a Stephen Burrows go-see, "Burrows asked her to keep the look for his runway show and, defying her agency's wishes, Evans agreed," Arogundade reported. After that, she became one of the highest paid '70s fashion models, coming in behind Twiggy, the original supermodel.

This was arguably a major moment not only for fashion, but for women of color. Standing in stark contrast to the garçonne, Bambi-eyed models who jumped in go-go boots across Vogue editorials, Evans introduced an amendment to society's definition of beauty.

Arogundade explained, "From the very beginning, Evans was troubled by the industry’s preoccupation with straight hair, and the pressure placed on model women of color to conform to white beauty values. She decided to make the strongest aesthetic protest she could — by adopting a bald-head shave."

It could be argued that much about women's personal aesthetics becomes inherently political, thanks to institutionalized sexism — from the way we dress our bodies to what cosmetics we pack in our purses — so the choice to shear off hair feels heavy with symbolism. Evans used this to her advantage, not only rebelling against the constraints put on women, but on women of color.

2. Grace Jones In The 1970s

Grace Jones was another powerful player in fashion who used her hacked-off 'do to reject the close-minded idea of mainstream femininity.

Originally from Spanish Town, Jamaica, Jones seemed to have the kind of grit that caused New York city to welcome her with open arms rather than throw her the usual middle finger reserved for most outsiders. A hot piece on Studio 54's dance floors, a regular on the couches at Andy Warhol’s Factory, and a ferocious Bond Girl, according to the New York Times, Jones quickly became a pop culture icon.

Her androgynous, borderline predatory look only helped. Either sporting a traditionally masculine flat top or going completely buzzed, her gruff cuts set the tone for Jones. As Vogue pointed out, "[...] Grace Jones’ ultrashort hair was so fitting: A close-to-the-head crop nonverbally communicates that you are a woman who isn’t going to ask for permission."

Transcending gender norms, she not only rejected mainstream femininity but challenged the paradigm of what it meant to "look" your gender. In a 2015 interview with Dazed, she shared, "I feel feminine when I feel feminine. I feel masculine when I feel masculine. I am a role switcher." Instead of letting society nudge her into a box, she still exudes fierce self-possession: She decided who she was, on her own terms, and stuck with it.

Evans further explained her need for control in her memoir, I'll Never Write My Memoirs, which Vogue shared an excerpt from: “I never ask for anything in a relationship because I have this sugar daddy I have created for myself: me. I am my own sugar daddy. I have a very strong male side, which I developed to protect my female side. If I want a diamond necklace I can go and buy myself a diamond necklace.” She not only redefined female strength, but encouraged many women to claim a type of fierce ownership over their identities: An ownership that doesn't need to fit a narrowly-defined role.

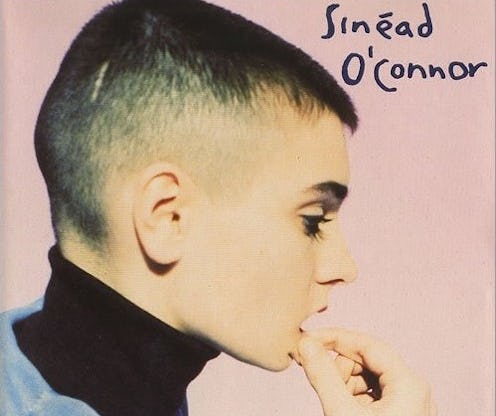

3. Sinéad O'Connor In The 1980s

Sinéad O'Connor is an iconic bald icon who came to fame in the '80s, and while her cropped look helped her make an imprint on the public's mind, her reach for the clippers had a feminist motive.

O'Connor shaved her head to push against old-school rules that were tagged on women, pushing away a sexuality she wasn't comfortable exploiting. Vogue reported, "Sinéad O’Connor, who headed straight for the barber’s chair when record executives suggested miniskirts and hip-grazing hair, [made] an empowering move that’s defined her ever since."

Not only did she shut the door on the male gaze, but her peach fuzz of a cut helped highlight an aspect of womanhood that was typically glossed over in the mainstream: The risks that came with being female. Her lack of length was loaded with symbolism.

As reported by The Huffington Post, she told Oprah in 2014, “I had grown up in a manner which... I’m sure a lot of women will relate to, where it was dangerous to be a female. So, I always had that sense that it was quite important to protect myself — make myself as unattractive as I possibly could.” Although there are dangers in pushing women to strive for conventional beauty, there also exists, for many, a dark need to posses that beauty. This can create dangerous and violent situations for women. O'Connor used her aesthetic not only as an identity, but as a reminder to the public of this unfortunate reality.

4. Ève Salvail In The 1990s

When French-Canadian model Ève Salvail walked for Jean Paul Gaultier's spring/summer '94 show, the audience was met with something unexpected: Here was a supermodel in the making walking down the runway in a dress that was all elegance, with her head not only buzzed, but with a coiling dragon tattoo stretched across her scalp.

"Despite the shock of attendees, though, no one could quite ignore Salvail's arresting beauty. It was less that it existed in spite of her shaved head and more that it was inextricably complemented by it," Fashion Magazine reported.

Shiny bald heads and fierce dragon tattoos were, and remain, largely considered traditionally masculine, which Gaultier decided to play with and, ultimately, question. Dazed reported, "Two traits considered traditionally unfeminine, Gaultier amplified the statement by dressing [Salvail] in a trailing gown. Her striking looks were undeniable, though, and, in this way, the designer forced people to consider the beauty in the unexpected — Salvail went on to be one of the defining faces of the decade." She unquestionably made the public question why femininity was so narrowly-defined, and why it couldn't allow for different, varying translations.

Not only that, but Salvail also helped fight the tired tropes of lesbian stereotypes. Coming out as gay in 2007, she challenged the idea that queer fashion was somehow "less than." Writer Zoe Whittall of Fashion Magazine pointed out, "Lesbian élan was, and sometimes still is, seen as an oxymoron." But here was Salvail, one of fashion's supers, walking down the catwalks of Paris and Milan: Androgynous, a lesbian, and arresting.

Whittall continued, "She represented an overtly androgynous presence in the fashion industry and seemed, to me, as rare and queer as a glitter-encrusted rainbow unicorn." She helped push the idea that just because one doesn't look traditionally "ladylike" doesn't mean they are any less of a woman.

5. Alek Wek In The 1990s

South Sudanese British model Alek Wek's arrival on the London fashion scene challenged not only the industry's no-new-friends-club mentality when it came to diversity, but helped restructure the Eurocentric outline of black beauty. Fleeing to Britain from a civil war-torn Sudan in 1991, Wek was quickly picked up by model scouts in London. Not only did she help break up the white-washed couture runways, but her appearance helped expand the mainstream perception of who and what could be considered beautiful.

Vogue reported, "Though Wek was far from the first African model to be embraced by the fashion industry, she was one of only a handful of dark-skinned models to rise to prominence during the era of the Supers." Why was this important? Because she stayed true to her heritage along with it. While many models of color did walk the couture runways in the '90s, they were often encouraged to acquire more stereotypically white styles, with straightened, long hair, for instance. But Wek, with her unapologetic buzz, ebony skin, and bold features, forced the industry to deal with the fact that she was beautiful as well. She didn't need to fit into a white checklist, and she knew it.

The Guardian reported, "At a time when black models were considered commercially more viable if their hair was relaxed, their complexions light, Wek was confident of her value. I have interviewed many models and, without fail, when asked if they always knew they were beautiful, each of them has given me a look of mock horror before going on to list their unsightly features as a child: Big feet, too tall, gawky features. But when I ask Wek, she immediately replies, 'Oh yes, of course.'"

Wek didn't necessarily stay true to her aesthetic just for women of color, though. She was setting an example for women everywhere. She explained to The Guardian in 2014, "It wasn't even about black or white, it was about women. I felt that girls growing up needed to see somebody different, who may have been criticized for their nose, or their hair, or anything — that they could be beautiful. You don't have to go with the crowd." She wanted to show all women that they were seen and appreciated, no matter how far they strayed from the arbitrary, unrealistic standards of female beauty.

6. Ruth Bell In The 2010s

From McQueen to Burberry, Ruth Bell's peroxide buzz has turned up on more than a fair share of catwalks and glossy pages. Why did her crew-cut catch the attention of so many designers and magazine editors? It might have a little something to do with her strength of character.

Sable Yong, a freelance beauty editor who has worked with Teen Vogue, told i-D, "Now that beauty trends have shifted to focus on the individual and celebrating uniqueness, I think women are more encouraged to make the bold move [...] The difference of perspective now from say 20 years ago is that you're not necessarily losing anything but hair by shaving your head. It's just another avenue for self-exploration and self-representation."

Bell's quick rise to golden girl status showed how hungry the industry was for something different. The New York Times explained, "The modeling industry, like the film industry, is full of star-is-born stories. Miss Bell’s came with a set of clippers. She is not the first successful model to wear her hair in this style — think of Ève Salvail, once a great muse of Jean Paul Gaultier, or Alek Wek — nor at the moment the only one. But the style has made her name nearly instantaneously."

This might be because the look is still considered edgy, but it also might be because of the fashion industry's new — albeit slow — restructuring of what is beautiful. Character, individuality, and quirks have snuck into the definition, with a celebration of the "other" arguably arising. From a rise in androgyny in recent seasons, to slightly increased representation of curvy or differently-abled models, more room is being made.

“I did the Acne show, and there were five girls with shaved heads,” Bell told New York Times in 2015. “One girl came up to me and was like, ‘Yeah, Mert and Marcus shaved my head because of you.’” Beauty is, slowly, getting a new definition: One that's starting to revolve more around self-possession than tired formulas.

7. Kris Gottschalk In The 2010s

A close crop can represent a kind of strength that becomes less of a question when a woman goes nearly bald. It shows that she doesn't need to hide, nor does she care to.

Model Kris Gottschalk recently shared with Teen Vogue that when she shaved her head, she “became more me — and this translates to how people perceive me as well [...] My short hair carries with it a sense of strength, independence, and self-confidence. Lots of designers want to associate their brand with this image.” Beauty isn't only to be found in blowouts and glossy pouts, but in strength and a strong sense of self.

Donatella Versace — a designer who's got "sex bomb" written all over her brand — cast Gottschalk this past season, arguably exemplifying the shift. “Donatella told us backstage that her woman was fearless, a fighter — like a modern urban warrior. I loved the association she made,” Gottschalk told Teen Vogue. “Fashion is becoming more open and receptive [to beauty that strays from the] stagnant standards and norms. Short hair can be sexy and feminine.”

And that's something the mainstream is slowly figuring out for itself. From Pat Evans and her clean-cut in the '60s to Ruth Bell and her bleached fuzz during Fashion Week, the message is simple: There isn't just one right way to be a woman, and those dated, narrow beauty standards should have no power when it comes to our image.

Images: Ohio Players (1); Island Records (1); Magazine (1); Yves Saint Laurent (1); Under The Influence (1); Chrysalis (1)