Books

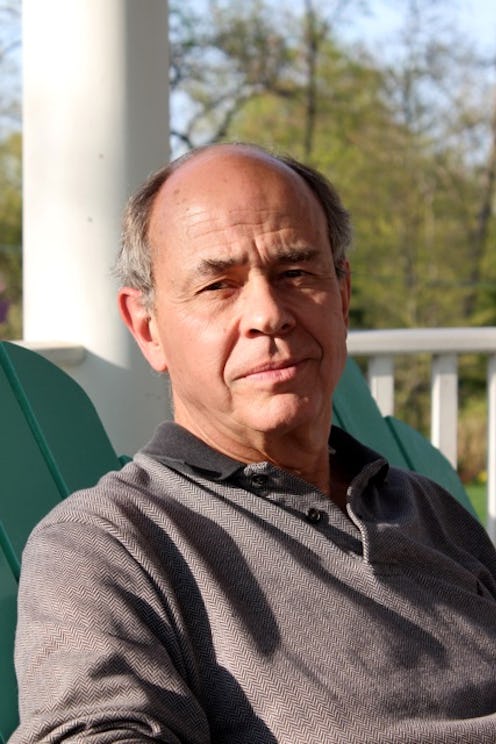

Q&A: Raoul Wientzen Talks 'The Assembler of Parts'

As the author of The Assembler of Parts (Arcade), Raoul Wientzen draws on over thirty years of experience treating critically ill children. However, his story of a Jess, who dies at age eight, and her family, who must go on with out her, is neither clinical nor maudlin (and, at times, surprisingly funny). The novel's strength lies in its characters — when they fall, it's tragic, but watching them pick themselves up is inspiring. Wientzen's own personal experiences play heavily into the novel, so we hopped on a call with the doctor-turned-author to talk tenses, thumbs, and family, and really get to the heart of the book.

BUSTLE: So you’re a physician, and you wrote a novel about a child who’s very sick. It may seem obvious, but when (or how) did you start writing this novel?

DR. RAOUL WIENTZEN: I am a physician, and I do pediatric infectious disease — that’s been my sub-specialty. So, for 32 years I’ve dealt with children sick with various infections on the faculty of Georgetown University Hospital. What has touched me over the entire length of my career is taking care of sick children. Some die, and many, if they don’t die, suffer tremendously before they’re cured. Seeing the effect of that, not only on the child, but also on the family… it had been in my mind to write a book about that. I wanted to try and explore why there’s evil in the world. Not in the sense of moral evil, but why is this world so imperfect.

It must be hard to see that on a daily basis. Did writing become an escape?

I've wanted to write forever, but in my clinical practice, and in an academic setting where you have to teach and research and publish and see patients, I never really had the opportunity to sit down and do it. But a few years ago, I switched from my full-time practice at Georgetown University Hospital to become the medical director for this foundation that manages international healthcare. So five years ago I started writing in earnest.

And that’s when you started writing The Assembler of Parts?

Sort of. On a Superbowl Sunday I was asked by one of my friends to meet with a young man who wanted to go to medical school. And I said sure, I’ll go talk to him. My neighbors across the street bring him over at halftime, and he has Hilgar's syndrome [the same syndrome as Jess, the protagonist]. He has no thumbs, and cochlear implants. But he’s brilliant, and he wants to be a doctor to help others. I was so taken with the humanity of this young man over the course of our conversation. Long story short, he was accepted to med school. I haven’t followed his career, and I don’t want to. I don’t believe he knows about the book — I certainly didn’t write it about him, but their struggles are similar. So, that’s what got me thinking about what a book with Hilgar’s could be like.

Besides this young man having it, was there anything about the idea of Hilgar’s Syndrome that struck you?

Anthropologists tell us what most makes us human are our opposable thumbs. Apes and chimpanzees have them, but they can’t use their thumbs to do a little dance with their other digits, so they can’t make nuclear weapons, or St. Mark’s Basilica, or a couch. They can’t use their hands the way humans can and that’s why we have civilization and society. So thumbs are what most make us human. But people with Hilgar’s don’t have thumbs. And I thought, well, let me start when this girl is a baby, and sort of chronicle the life she would have experienced. And then it evolved — the characters kind of lead me through the rest.

Did you always have the idea of setting up the novel when Jess had already passed away as a frame? Or did that come later?

I actually started right away. The way the novel is now published is actually exactly the way I wrote it. I remember going to the library that first day — my wife kicked me out because I was trying to write at the kitchen table. She told me I was too damn close to the peanut butter and the telephone, so I had to find someplace to write.

My next question was going to be about how you crafted Jess’ voice, but it sounds like it just came to you — is that because you work with sick children?

Yes, definitely. It’s the residue of so many children I had to take care of — I had the privilege of taking care of them over so many years.

Since her voice was so strong, were you a little worried about how the audiobook would turn out?

In my audiobook, I was enthralled by the sound of this young woman who reads the book. She has this voice that could be a child and could be an adult, and it’s wonderful. I was very touched with it—I might even buy the audiobook to listen to what someone else thinks Jess sounds like.

In the initial drafts, was there anything in particular you struggled with?

What I struggled with most were tenses — she’s alive in the afterlife looking at the past that’s sort of like the present, but there is no past and present in the afterlife, so it can get a little tricky.

Jess is pretty solidly set up as the main character, but I was always more invested in Cassidy, her alcoholic but painfully tender uncle. Did you anticipate that different readers would respond differently to your characters?

Yeah. I would say the responses are probably 50-50 between Cassidy and Jess. My male friends, actually, were more connected to Jess. A lot of the women connected to both Jess and Cassidy, and some even connected more to Cassidy than Jess — I guess because the related to some of the experiences Cassidy had, and how Jess was a balm to his sadness.

There have been some early comparisons between your novel and The Lovely Bones — have you read that novel at all?

I have never read The Lovely Bones, and that was on purpose. My wife had read it and after I gave her the outline of The Assembler, she told me about it. I didn’t want to read that book, as good as I understand it to be, and have it influence my choices. Sometimes isolation is important. So that’s about as much as I know about The Lovely Bones. The similarities between the two are child narrators from the afterlife, but I don’t know much more.

You said that you were trying to work through why bad things happen to good people — do you think it’s so they can all turn out as wonderfully as Jess does?

I think what I was designing was that Jess was a healing presence —and to some degree, she knew that about herself. She tells Cassidy and BJ they’re going to be okay. I think the idea is that Jess is fully human — thumbs or not — because she is fully forgiving of her family, and even God. But the idea is that you have to accept what’s imperfect and forgive what made it that way. While I was watching people in chaos with sick and dying children, I though if, somehow, the love in the family is intensified by it, it’s a little less painful, and maybe there’s some sense to it — if there’s any sense in the death of a child. I guess I was trying to get to that point. Forgiveness is the thumb of the hand—it’s what makes us human.

Image: Stephen H Mintz MD