TV & Movies

What Happened To Sleepover Movies?

Movies about teen girls were everywhere in the 2000s. Then they disappeared.

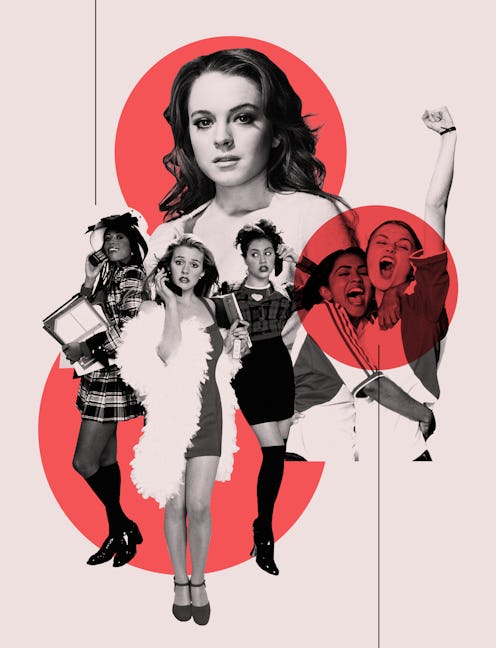

In 1996, The New York Times proclaimed that movies had “discovered the teenage girl.” “Consider the evidence,” Peggy Orenstein wrote, citing the release of films like Harriet the Spy, Manny and Lo, and Foxfire. It was the year after Clueless, Amy Heckerling’s deceptively smart comedy about a rich Beverly Hills teenager, unexpectedly grossed $56 million, and movies about young girls were sprouting up in droves. “Let me make this clear: I'm not talking about the traditional use of young women as plot devices,” Orenstein continued, but the films in which women are “in charge of their own fates, active rather than reactive; films that are about girls' relationships to one another rather than to boys.”

By the early 2000s, movies about teen girls were everywhere. Bring It On (2000), a culturally astute satire about two dueling cheerleading teams, raked in $90 million worldwide and spawned five sequels. Bend It Like Beckham (2002), starring a British-Indian teen torn between family and ambition, earned $76 million. Mean Girls (2004), an instant classic, bagged $130 million and hatched a decade’s worth of memes. What films like But I’m a Cheerleader (1999), Love & Basketball (2000), and Real Women Have Curves (2002) — a clear influence for Greta Gerwig’s Lady Bird — lacked in box office prowess they made up for in lasting cult acclaim, prompting anniversary screenings and routine think pieces.

“Part of what made these movies so impactful is that they spoke to teenage girls on a very personal and visceral level,” says Refinery29 film critic Anne Cohen, whose column “Writing Critics’ Wrongs” re-examines movies from this era. “They addressed our fears, our desires, and our ambition without judgment."

"But then 2010 hit, and the sleepover movies disappeared."

They were also, notably, written by and for women — some irreverent, others tender, but all comforting in that they provided a sense of shared understanding. I call them sleepover movies because that’s where I watched them, nestled into the worn leather of my friends’ couches with pretzeled limbs, surrounded by junk food, awash in the blue light of worlds that felt like they were ours, and also intimately mine.

But then 2010 hit, and the sleepover movies disappeared.

Though the early 2000s had been a boon for women filmmakers, they were also somewhat of a fluke. According to the Center for the Study of Women in Television and Film at San Diego State University, the number of women screenwriters was at a high point in 2000, at the meager tally of 14% among the top 250 films. By 2006, that number had dipped to 10%, while women directors dropped from 11% to 7%. Women continued to make strides in the 2010s — setting their sights on animated features and action tentpoles — but despite the prevailing narrative that gender parity was improving in Hollywood, the statistics remained relatively stagnant. "When I started [tracking these numbers in 1998], I thought it was merely an issue of people not knowing how low the numbers were,” Martha Lauzen, the head of SDSU's research center, told Women in Hollywood. “I didn’t know how slow social change is.”

“There's still a large part of our country that doesn’t want to hear young women cuss or talk about their sexuality or have agency over their bodies.”

The industry had also turned its attention elsewhere, to YA franchises like Twilight and The Hunger Games, which both centered on teen girls but featured supernatural forces and big-budget action. “A lot of movies for teenagers are now based on young adult novels, because Hollywood knows those are already popular stories, and older adults like them too,” says Christina Hodel, a filmmaker and professor at Bridgewater State University. “They still feature the same tenets that we saw in teen movies of prior decades, but they’re dressed up a bit differently."

Combine that with the rise of streaming, the downfall of Blockbuster, and the changing tastes of Gen Z — who grew up in a post-9/11, digital-first era of political turbulence and rampant social media — and the demise of sleepover movies seems inevitable. “My 16-year-old sister and her friends don’t even think to watch a movie” during sleepovers, says Willa Bennett, a senior social media manager at GQ who's spent much of her career analyzing the media habits of Gen Z. “They literally just watch YouTube for hours… obviously that’s not everyone, but the cadence of entertainment has changed.”

It’s not that movies about teen girls vanished completely. There was the French indie Girlhood (2014), Kelly Fremon Craig’s The Edge of Seventeen (2016), and Gerwig’s Lady Bird (2017), a wistful depiction of the fraught relationships between mothers and daughters. 2018 featured a handful of critically acclaimed films about teen girls, from the police brutality YA drama The Hate U Give and the poignant coming-of-age story Eighth Grade (which was written and directed by a man, Bo Burnham) to Kay Cannon’s prom-night raunch comedy Blockers, which landed her among the select circle of women who’ve directed R-rated films. Olivia Wilde joined her with 2019’s Booksmart, an infectiously joyful salute to the special bonds forged between young women. But while still influential, few of these films were able to achieve the same crossover appeal as their predecessors.

Things have gotten better in recent years. As of 2019, the number of women screenwriters was at a historic 19%, while women directors were at 13%. Once again, we find ourselves at what seems like the threshold of progress, though it’s tempting to see this as another streak of false hope. In the face of the coronavirus pandemic, the film industry’s fate is as uncertain as ever.

But I prefer to look at these movies as a testament to the formidable power of women’s persistence. None of them were easy to make. Heckerling says she was encouraged to focus more on the male characters in Clueless, despite the fact that it’s told from Cher’s perspective. Jessica Bendinger pitched Bring It On 28 times. Co-writer Kirsten Smith says 10 Things I Hate About You (1999) almost didn’t get made because Disney had decided it would fund exactly one film about teen girls and it was up against another movie called School Slut. Booksmart had been floating around Hollywood since it landed on 2009’s coveted Black List. Even Blockers’ Cannon, who describes her team as wonderful and supportive, was usually the only woman in the room, fighting for the right to let teen girls make dick jokes.

“Sometimes [the men in the writer’s room would] really be tiptoeing around it like, ‘I don’t even think a guy would say that.’ And I’d be like, ‘Oh really, you don’t think a guy would make a joke about masturbation?’” she says. While pitching Blockers, she was asked why a young woman would ever buy a ticket to see it. “There's still a large part of our country that doesn’t want to hear young women cuss or talk about their sexuality or have agency over their bodies.”

And yet, according to the $94 million it made in ticket sales, there is a large part of the world that does.