Books

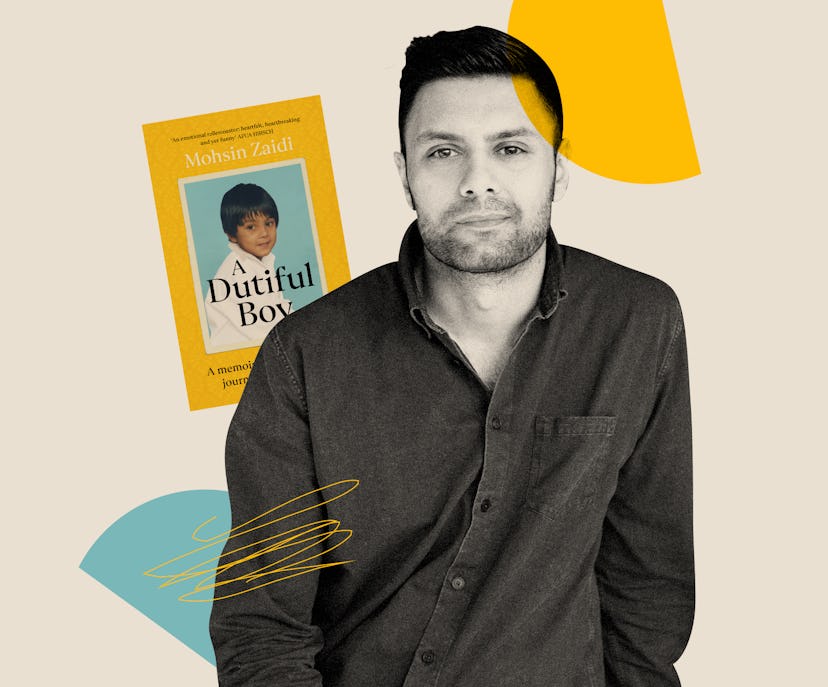

Mohsin Zaidi’s Memoir A Dutiful Boy Is A True Act Of Bravery — EXCLUSIVE EXCERPT

Zaidi's account of what it’s like to grow up Muslim and gay delivers a message of universal relevance.

At face value Mohsin Zaidi's memoir, A Dutiful Boy: A Memoir of a Gay Muslim’s Journey to Acceptance, is coming of age story. It recounts Zaidi's experience of growing up queer in a devout Muslim community and all that entails: the solitude, the fear, the shame. Against all odds, Zaidi achieves a ridiculous amount, becoming the first from his state school in East London to attend Oxford, and then become the accomplished criminal barrister he is today.

But beyond that, Zaidi's memoir is the identity narrative we need today. It confronts race, sexuality, faith, class, education, and mental health with extreme bravery and searing honesty. Most remarkable of all is the balance with which Zaidi approaches it. Whether he's talking about how he repeatedly pleaded with Allah to be straight, how he couldn't answer his therapist when asked whether his parents would rather a gay son or a dead son, or how a witch doctor was called in to "cure" him, Zaidi's voice remains disarmingly fair. He's almost surgical in his language: descriptive and analytic, but ultimately free of blame.

The result is what Afua Hirsch rightly calls "an absolute emotional rollercoaster". One minute you are crying in anguish at the clear solitude Zaidi felt growing up. The next you are disgusted by the explicit racism he experienced at university (where his name was frequently mispronounced as "Martin") and the blatant discrimination he faced on dating apps (where "no Asians" and "no Pakis" are common profile preferences). Peppered throughout are moments of sheer joy though, like when his brother Abbass asks whether KFC, which he's not allowed to eat because it isn't halal, is as tasty as it looks. ("‘Yes, I have tried it and it’s fucking delicious," Zaidi tells him.)

In this excerpt from A Dutiful Boy, Zaidi is working at the apex of the British legal hierarchy as a judicial assistant to the justices of the Supreme Court. Though he's come out to his family, he very much keeps his private life to himself, until one particular assignment hits rather close to home. It is a perfect snapshot of Zaidi's book: as heartbreaking and profound as it is brimming with humanity, insight, and ultimately, hope.

The bravery of this book and importance of its message cannot be overstated. Love does always win, and acceptance – particularly now, in these "unprecedented times" and in our multicultural society – is the only way forward. The world is a better place for having this memoir in it, and we'd all do well to take a page out of Zaidi's book.

Mohsin Zaidi's memoir, A Dutiful Boy, is published by Square Peg and out now.

Excerpt from A Dutiful Boy, exclusive to Bustle UK

I worked closely with Judge Lord Wilson from the start, who expected me to meet him in his office at 9 a.m. each morning to discuss the day’s upcoming case.

‘Good morning, Mohsin,’ he said in his cut-glass accent. He had thick, white, slicked-back hair and a wide smile.

‘Good morning, Lord Wilson.’ The court decreed that judicial assistants had to address the justices by their title, rather than their first name. It demonstrated respect for the institution.

‘I’ve been invited to give a speech to the Medico-Legal Society at Queen’s University in Belfast,’ he said. I stared at him blankly. ‘A group of Northern Irish lawyers,’ he explained. ‘Given my background in family law, I’d like to make a speech on gay marriage and I’d like your help.’

I froze, wanting the floor to open up and suck me in.

‘Yes, of course. What can I do?’

‘Well, as you know, gay marriage is not yet legal in Northern Ireland.’ ‘Yes.’

‘Well, I’d like to illustrate how ridiculous this is through historical and current examples of marriage. I want to show that the concept was man-made and can therefore be adjusted by man.’

I wanted to come out to him right there and then but it was irrelevant and, more to the point, unprofessional.

‘Of course, Lord Wilson. I’ll get to work straight away.’

The speech went through at least twenty-four drafts and each draft brought with it more queries to resolve and quirky examples to find. During the course of working on the speech, I noticed Lord Wilson’s formidable literacy didn’t extend to computers so I lent him my new iPad in an effort to demonstrate how easy they were to use. Two days later he had acquired his own. It was the first time he would have an email address.

Every minute of working on the speech taught me something new; I was doing something that mattered. Lord Wilson effortlessly, politely and humorously dismantled the arguments levelled against gay marriage by using examples throughout history of how human beings had changed the concept of marriage to suit themselves. His ability to sculpt words into an attractive argument was akin to watching Michelangelo work with marble I imagined. The first time I read his concluding statement, I welled up.

The most important benefit of same-sex marriage is the symbol that it holds up to the heterosexual community, not forgetting teenagers apprehensively trying to make sense of their own emerging sexuality, that each of the two types of intimate adult love is as valid as the other. The availability of marriage properly dignifies same-sex love. To the question ‘why should same-sex couples, who can as civil partners already enjoy all relevant rights, be allowed to get married?’, the proper response in my view is ‘why shouldn’t they?’

I had to pinch myself to make sure I wasn’t dreaming. Not only did I have the most interesting job a young lawyer could do, but by extraordinary luck, I was also working on a project that held a deeply personal significance.

When he returned from his trip to Ireland, we celebrated in his office. ‘Lord Wilson, aside from learning so much, there is another reason why I enjoyed working on the speech.’

‘Oh?’ he said.

‘Well ... um ... actually ... I’m gay. I didn’t tell you before because I thought it unprofessional, but now that the speech is over and we’ve been working together for a while I wanted to say how honoured I feel to have had the chance to work on it with you.’

He smiled with his characteristic warmth. ‘Mohsin, I hope you won’t mind my saying, but I already knew.’

‘Oh?’ I sat up straighter, uncrossing my legs.

‘Yes – not because I could tell or anything,’ he said hurriedly.

‘Oh?’ I seemed to have no other words in my vocabulary.

‘Well . . .’ He paused long enough to make us both uncomfortable. ‘You know when you lent me your iPad?’ ‘Yes ...’

‘Well, you might recall that I returned it to you rather hastily?’ I nodded. ‘You see, these rather colourful messages kept popping up from a young man called Alejandro ...’ It suddenly occurred to me that my iPad was synced with my phone. ‘Of course I tried not to read them but they were rather insistent ...’

OH. MY. DEAR. GOD. I opened my mouth to speak, but all that came out were the stuttering noises of shame. He had read naughty messages between me and a fiery Spanish guy I’d met on a night out.

‘Now, Mohsin, there is absolutely nothing to be embarrassed about and I do hope you don’t mind me having said something but I thought it better to be truthful.’

‘Yes ... of course. Um ... if you’ll excuse me ... I have to ... go,’ I said before darting out of the room.

A little later, I returned to his office and we laughed about it. That laughter pierced the thick layer of formality between us. Once upon a time, an incident like this would have left me desperate and ashamed but not any more. Living a truthful life meant I could be less careful with my secrets. It meant I could just laugh. And Lord Wilson wasn’t the only judge to embrace the whole of me. I had expected to suppress parts of myself to fit in, but the entire Supreme Court welcomed me for who I was.

This article was originally published on