Entertainment

Dr. Orna Guralnik Wants You To Push Boundaries, Not Set Them

The star of Couples Therapy goes viral for dispensing tough love, not automatic affirmation.

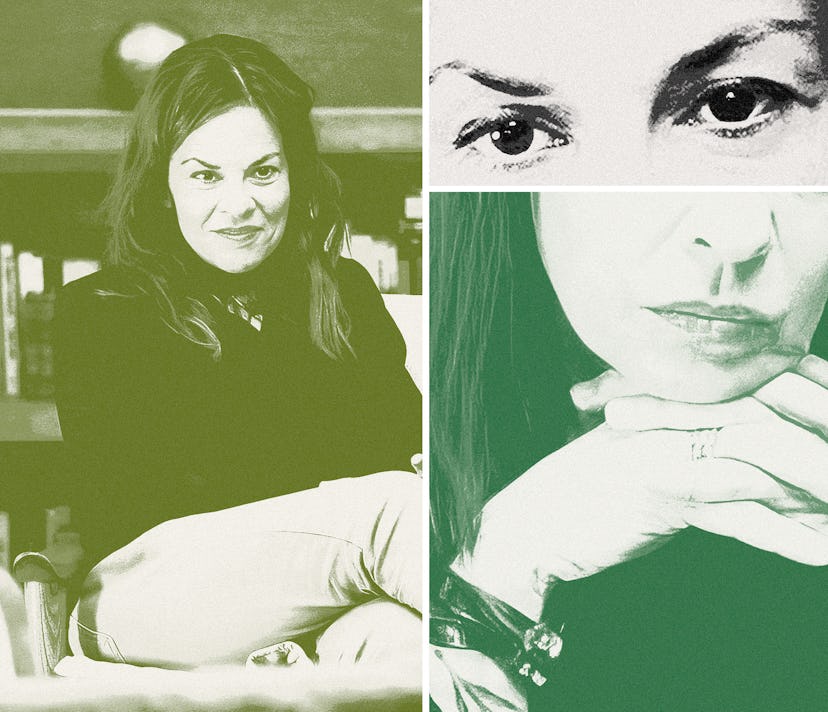

Dr. Orna Guralnik is trying to solve a problem. She sits quietly, staring with an expectant frown that seems to inspire a need in whoever’s sitting across from her to produce an answer. I have watched her make this face many times before: on three seasons of the Showtime docuseries Couples Therapy, in which the psychoanalyst and clinical psychologist delivers the titular relationship counseling, and on the clips from the show that have become an unlikely TikTok hit.

Right now, though, Guralnik’s focus is not on the deep excavation of the mind, but on what to order for dinner. We are at one of her regular spots in Park Slope, where she lives and practices, but she reads the entire menu before deciding what she wants. During the meal, she worries aloud that TV has made her less patient, less likely to “meander” with her clients. “In analytic work, you want to spend a lot of time and space close to people’s unconscious mind,” she says in her cashmere murmur. “Working on the show, it’s short-term treatment: You’ve got 18 weeks, it’s going to be wrapped up. It has to have a certain arc that makes sense. You want to yield results. It’s more pragmatic.” Watching her take three mostly silent minutes to order kale, fish, and a “rich” red suggests she has retained her willingness to ride the scenic route. She seems as unperturbed being observed in daily life as she is being filmed in the intimate act of psychoanalysis.

“Patients look at us intently and intensely all the time,” says Eyal Rozmarin, Guralnik’s friend and colleague of nearly 40 years, who appears on Couples Therapy as a peer advisor. He thinks clinical work has prepared Guralnik for her new status as a celebrity psychoanalyst. “It is kind of something to just stay, to be able to do that thing, whether it's to treat people, or to think about or to talk about yourself, to have your own privacy, even though [Guralnik is] being looked at by increasingly larger circles of people.”

Guralnik has been informed of her popularity on TikTok, though she doesn’t have her own account. Fan-made clips — with exalting captions like “Orna has the patience [of] 3 saints!!” — circulate well beyond the conclusion of each season, and not just for the pure voyeurism of listening in on strangers’ most private problems. Guralnik has gone viral by making people confront the reality that life is pain — and joy, and anger — and getting them to figure out why they feel these things when they do. The pleasure in watching Guralnik push and push someone until they have a revelation about why their relationship is so f*cked up is like a non-disgusting psychological version of a Dr. Pimple Popper draining a blemish.

[My patients] can be annoying as f*ck in certain sessions or periods, but I love them.

Her empathic tough-love approach also feels refreshing against the relentless validation of the current mental-health milieu. The usual darlings of TherapyTok tend to speak to the camera in mental hygiene-improving lists: Micheline Maalouf’s step-by-step guides for recognizing and halting panic attacks, TherapyJeff’s relationship coaching checklists. The implicit promise of such content is somewhere between the mental health management techniques of cognitive behavioral therapy and the avoidance of pain: cutting out toxic people and behavior while practicing compassion and kindness toward yourself. Guralnik’s appeal, on the other hand, lies in her insistence on questioning boundaries, rather than affirming them, or even using the omnipresently squishy therapy-speak of “boundaries” and “narcissists” and “protecting your peace” at all. Gaslighting is “not a helpful concept,” Guralnik says. “It’s so overused.” In her estimation, the messiness of life belies neat labels and tidy answers.

We’re speaking in late October, and the Israel-Hamas war keeps coming up, prompted by seemingly unrelated topics. At one point, Guralnik discusses two clients from Couples Therapy: a wife who wants to live by her ideology, and her husband, who found his lived experience did not match his wife’s ideals. “I’m also very attached [and] connected to my feelings, so I relate to that tug,” Guralnik says. “Which can easily bring this to Israel-Palestine.”

The conflict is personal for Guralnik. She grew up in Israel and has family and friends there right now. Rozmarin remembers the two of them going out dancing and attending house parties in their 20s, just like the kids who were murdered at the Supernova music festival on Oct. 7. “Since this war broke out,” Guralnik says, “my dreams are absolutely insane. There’s a lot of defending, fighting, shooting. It’s incredible to me, the degree to which this war has infiltrated every corner of my mind. I have no escape.” Even in sleep, Guralnik’s feelings are complicated: “In my dreams, I’m debating whether Israel has a right to exist or not.”

Guralnik has been having productive conversations with Palestinian colleagues. “There’s a small group of us that are talking and talking and talking through it and not breaking down,” she says. “That comes from an ideological position of ‘I’m going to make an effort to not only see my own pain but to see yours too. And when I fail, I’m going to try again.’”

Though there are limits to paralleling a millennia-long religious and territorial conflict to relationship issues, Guralnik says the principles of working through aggrievement can be applied to other dynamics that feel intractable. “Being able to say, ‘I see you. I see what’s bothering you,’ is huge,” Guralnik says. “That changes everything.”

Guralnik is an unlikely reality star. She’s beautiful but didn’t make her premium cable debut until she was in her 50s. In addition to her own full-time practice, she teaches at NYU and the National Institute for the Psychotherapies. One of her best friends, Betsey Schmidt, says both their friend group and Guranlik’s psychoanalytic community were “super concerned” about her appearing on television; not least because it’s a medium Guralnik doesn’t even watch, except for French news programs. “This seems like a really big risk to your profession and to the seriousness with which you built your career,” Schmidt says she and others told Guralnik.

Couples Therapy was created by documentarians Elyse Steinberg and Josh Kriegman, who began delving into the hidden parts of romantic partnerships while making Weiner, the would-be comeback story of omniscandalous New York politician Anthony Weiner and his 2013 run for mayor of NYC. Partway through the documentary, it becomes a psychosexual drama: Weiner is again caught sending graphic extramarital messages, and every interaction with his wife, Huma Abedin, becomes laden with the subtext of words unspoken — or at least not spoken in front of cameras, which Abedin seems to deeply wish weren’t there. Guralnik was a fan. “That kitchen scene is unforgettable,” Guralnik says of Abedin quietly calling her life a “nightmare” after a rictus-tense moment between the couple.

“Often I have to put a lot of pressure on the woman to change things before the guy can do anything. It’s not fair, but that’s the only way things will change.”

If Steinberg and Kriegman’s doc demonstrated a mass appetite for nuanced relationship issues — and a test case for a couple who may have benefitted from enhanced communication tools — Guralnik provided Couples Therapy with a moral and clinical rigor to keep it educational and not prurient. Plus, as the filmmakers have said many times, they just like her. It’s hard not to. Behind Guralnik’s intellectual gravitas is a deep affection for the people she works with. “They can be annoying as f*ck in certain sessions or periods,” Guralnik says of grinding through therapy with her patients, “but I love them.”

Guralnik was convinced to sign on when she realized her mission aligned with the creators’: to demystify psychoanalysis. And not just to strangers. Before the show, Guralnik’s daughter, Ruby, had never heard her mother talk specifically about sessions; it would violate the ethics of the practice. Through watching Couples Therapy, both on set and on TV, she was able to grasp the marvel of her mother doing that kind of emotional-intellectual work without ever treating her kids like clients to be analyzed. “I gained a lot of understanding and sympathy for my mom after seeing what she has to do every day, and also seeing her be so good at it,” Ruby says. “It’s such a unique experience to have to take care of other people all day long and then come home and continue to take care of people — your kids — all day long and all night long.”

Though Guralnik cannot help but therapize me — “What would he say if you asked him about that?” she pointedly says when I make an offhand comment about my husband — anybody who watches Couples Therapy ambiently absorbs its lessons. The show models replicable ways of listening and asking questions, of our partners and ourselves. “What happened there?” is a common Guralnik expression, as is a raised eyebrow, chin-down face Guralnik calls “the suspicious questioning look.” Sometimes she’ll just say, incredibly slowly, “Why?” or prompt someone to say more with a “Because…” She’ll call out insensitive behavior, but she’ll also tell you when you’re getting in your own way. “It’s really easy to look for the thing [your partner does] that will trigger your fear or your resentment,” she told one couple. “But what’s available to you are also really good things right there on the table.” One wife says that when her husband doesn’t keep his word, she has a VHS tape that replays in her mind of all similar past grievances. “The VHS tape is designed to enforce the feeling that you do not matter,” Guralnik tells her. “That tape is your enemy. That tape is your prison.”

“In a way, if people don’t become really attached to their analyst, not enough work would happen.”

Schmidt, who goes on Prospect Park walks with Guralnik and their dogs, has witnessed viewers come up and share their success stories. “I can't tell you the number of couples who've been like, ‘We actually were able to work out some things between ourselves because of it,’” she says.

No matter how obviously right one person is and how wrong the other, on Couples Therapy — and in real life — both have to change to make the partnership work. And while the “bad guy” in the couple might become better by going toward the light, it never puts the “good person” in the wrong to meet their partner where they are. One example Guralnik gives is the division of labor in heterosexual relationships. Emotional labor, child care, and taking care of the home often fall to women. When a man comes into therapy knowing that’s an issue and feels like it’s a trick to get them to do something, they can shut down. “Often I have to put a lot of pressure on the woman to change things before the guy can do anything,” Guralnik says. “It’s not fair, but that’s the only way things will change. Just turning to the guy and saying, ‘Why don’t you do more?’ is not going to work.”

Though Guralnik often knows what a couple needs to do to “fix” the relationship — which at times might entail ending it — the challenge, and the reward, is finding how to get them to realize it themselves. “It’s fun to figure out,” she says. “It’s like a riddle: how to get to this person, how to get to this person. How am I going to connect with them? If I have a hypothesis that this is going to be the great point of leverage — I’m not always right — is it going to change something over there?”

Unlike a discipline where the facts are what count, there’s a lot of imagination and drama in psychoanalysis. (That’s probably why it’s such good TV.) Compared to the more common psychotherapy, which deals with managing your reactions and behaviors, psychoanalysis digs into unseen crannies of the mind. The practice, currently in the midst of a small resurgence, is based on the idea that we are all guided by unconscious motivations formed earlier in life. Those experiences are acted out presently in the form of stand-ins — that’s why you’re fighting about pasta when it’s not about the pasta — and the goal is to trace what’s going on now to its inception so you can understand why you’re doing what you’re doing. It is a collaborative process: the show’s clinical adviser, Virginia Goldner, and the peer supervision group Rozmarin is part of help Guralnik analyze and ground her work in reality. “We try to not only see shadows on the wall,” she says. “That’s one of the reasons we do things with supervision.” Her colleagues listen to her discuss her sessions (and in the case of Couples Therapy, view footage), then muse through what might be driving these people and how to spur them to realization, talking about patients the way creators in a writing room might talk about their characters.

“Every patient that I’ve taken in has changed me,” Guralnik says. “People can just stay the same and inflict damage on themselves and others, and they chose to tackle themselves and do something different. And everything that happens, it’s kind of amazing. They pull themselves out of rigidity or a selfishness or very traumatic life circumstances. It’s inspiring every time. Every person does it differently. They bring out some resources that you didn’t know were there. And they teach me how to do it when they do it.”

If by this point you’ve imprinted on Guralnik and want her to fix you, join the club. “That’s sometimes a necessary phase,” she says of patients liking their mental health professionals a little too much. “In a way, if people don’t become really attached to their analyst, not enough work would happen. The depth of attachment and connection to feeling is a door towards deeper work. So it’s OK.”

So while I’m here with this person I’m slightly too attached to because I’ve seen her transform so many seemingly hopeless cases, I have to ask: What do we as humans really want? “I think we all want to be told who we are, what to do, what’s going to be better,” she says. “One of the things I remember finding so amazing in yoga is that the teacher tells you what to do, when to breathe in, where exactly to put every part of your body. You don’t have to think about anything. You’re just told. And just the relief of an hour doing that is just amazing to me.”

“Every patient that I’ve taken in has changed me They pull themselves out of rigidity or a selfishness or very traumatic life circumstances. It’s inspiring every time.”

In person, Guralnik can certainly be that authoritative, and even sometimes bossy, presence. She recently asked Rozmarin to join her on a worldwide lecture series on psychoanalysis, and when he hesitated, he says Guralnik told him, “No, I really think you should do it with me because this is what's going to happen. This is the kind of experience we're going to have. We're going to be traveling around the world together. And we're going to be developing something together. So I think you should do it. It will be good for you and I want it.” (She was right, of course. “I'm definitely glad that I followed,” Rozmarin says.)

But in a therapeutic setting, telling people what to do rarely works, and usually only if the person responds to a simple directive and immediately sees positive results. Though everyone thinks they want that yoga-level instruction, “they would never do it. Or their resistance would kick up so badly that they would sabotage the whole thing,” Guralnik says. “When people do analytic-type therapy, they have to go through the phases: First wishing the analyst will be telling them what to do, then having to go through that disappointment — the empty space of the analyst listening more than telling, which is frustrating for people. Then they get to enjoy the space.”

It feels like we all want to have done the work. To have reached the summit of mental health. To have put in our hours, dutifully completed our routines. To get to enjoy being psychologically fitter, happier, more productive. “We all want the world to come to us and not have to do anything,” Guralnik says. But she believes actually doing the work — as endless and nonlinear and maddening and ever-changing as it may seem — is the good part. “I think feeling like you’re changing is liberating,” she says of our desire to get better. “It’s exhilarating.” Maybe we’ve been gaslighting ourselves to think otherwise.