28

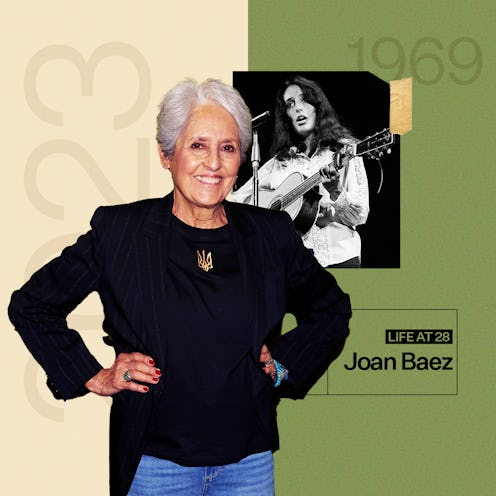

At 28, Joan Baez Was 6 Months Pregnant & Playing At Woodstock

The realities of the Vietnam War were always top of mind for the singer-songwriter.

By the time Joan Baez turned 28 in 1969, she’d been on the cover of Time magazine as the face of the folk music movement and was providing protest songs for an anti-war generation. She’d already sung to a crowd of 250,000 at the March on Washington roughly six years before, alongside her friend Martin Luther King Jr.

She was by then “addicted to activism,” she tells Bustle over Zoom. “[Fame] was a struggle. It gave me a lot more panic than I would’ve experienced [otherwise], but it also gave me an identity.”

In 1969, Baez performed at Woodstock while six months pregnant with her first and only child, her son Gabe, but her mood and circumstances that year were darker than those who were cheering the moon landing or vibing through the Summer of Love.

From the stage, she gave a shoutout to her then-husband, activist David Harris, who weeks earlier was taken to prison for protesting the Vietnam War draft. She herself had already been incarcerated for the cause. (At Woodstock, she sang “I Shall Be Released” by Bob Dylan, the ex who’d inspire and haunt her music for years.)

“[I remember] having an argument with my father, a physicist, about landing somebody on the moon,” Baez, now 82, says of that year. “We in the revolution didn’t want to hear about that. When there were people at home to be taken care of, why are we spending all this? So I didn’t allow myself the joy of watching somebody land on the moon. That was where I was politically and with my family.”

Those complicated family dynamics are a focus of her new, lifetime-spanning documentary, Joan Baez: I Am a Noise, which comes to Apple TV on Nov. 21.

Baez gave the filmmakers access to her late mother’s storage unit — she herself had never entered it — which contained childhood journals, home movies, and letters to and from her parents. The latter laid bare her allegations of childhood sexual abuse at the hands of her father and others, which her parents denied. The film even includes recordings of her therapy sessions, which she says have helped her heal.

The documentary amounts to an excavation of family secrets, all of which she’s sharing in an effort to leave “an honest legacy.” Why be so vulnerable? “It was time,” she says. “And the fact is, I have nothing to lose now.”

Below, the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame member talks about staying single forever, a new poem, and whether she thinks about Dylan.

You performed at Woodstock at 28 while six months pregnant. What do you remember about it?

What can you say about Woodstock? Well, you know what, I just wrote a poem about Jimi Hendrix. It’s about Woodstock. You wanna hear it?

Yeah!

Jimi Hendrix

You performed just before me at the Isle of Wight

And somehow lit the stage on fire

I performed in your wake as the aftermath flickered down through the floodlights

I sang strike another match, go start anew, and look out, the saints are coming through

You were no saint, but you certainly came through

You came through like a magnificent natural disaster

You came through like a f*cking hurricane

Like a f*cking volcano

At Woodstock, you eviscerated the National Anthem and made it your own

There were no bombs bursting in air or rocket’s red glare

There was only your guitar and 300,000 souls electrified in the dawn’s early light

Out there in the mud, out there in the volcanic ash

And you were only 27 when you died

Thank you so much for sharing that. I will be absorbing that for a long time. In your 20s, you were compared to Gandhi, and cultural critics called you “The Barefoot Madonna.” Were you aware of the impact you were having as it was happening?

I’m not sure I was. On the other hand, who really knows? Say at Woodstock, how much did we know how historic that was going to be? You find that out afterwards.

Tell me about your memories of Martin Luther King Jr. When you speak about him in the documentary, it brings up emotion, still.

I can’t hear him speak without having that reaction, because he was so meaningful in my life and obviously in the lives of millions. What people don’t get to see is his sense of humor. And I was gratefully in the inner circle, on and off, for a number of years. So I heard the folks, him and his lieutenants, joking constantly.

You talk about being “addicted to the activism.” By giving so much to the world, it also cost you personally. As we see in the film, your son really suffered from your absence while he was growing up.

I may have been addicted to it, but I chose things very carefully. There’s nothing I regret having done. The only way I think that it cost me [is] in light of what my son has to say in the film. It was difficult for me to watch. I was watching, “Joan Baez goes to Cambodia” and I’m thinking, “Why Cambodia? Why not with my kid?” Why, when I was really needed somewhere else, why did I go on being the do-gooder when I needed to be home?

That’s one of the most beautiful parts of the film. We see how close you are with him now.

I think it’s never too late to repair. I was joking that I’m going to start a “Bad Moms Club,” because so many of us feel that we didn’t do it right. I think it was exaggerated in my case, and I’m so glad my son was able to say what he said. And therapy was enormously helpful to us, to Gabe and me. We worked together.

Speaking of relationships, does it bother you that people are still interested in your relationship with Bob Dylan? Why do you think that is?

You know, I’m not sure. The stars lined up for a reason, but that doesn’t explain why it’s been so long-lasting. [It was] some kind of bizarre fairy tale.

I do think it’s important to add that all of the angst, bitterness, and nonsense ended when I painted a portrait of him. [I depicted him] at a very young age, and I started listening to his music and weeping. That went on for quite some time, probably until I finished the painting. It’s as though I washed away all of the BS that had been going on for decades. I’m free of that now, and can only be grateful for that time that I knew this kid, that I sang his songs. Instead of harboring negative stuff, I was fortunate to have it disappear.

When you sing “Diamonds and Rust” now, which was inspired by him, do you think of him?

It depends on the audience. If it’s an audience I’m not crazy about, I could be thinking about my grocery list. If it’s a wonderful audience, I know they’re fantasizing about the whole thing. But there are people who have no idea what the song is about. Yeah, sometimes I have images of way back then. And a lot of times I want to chuckle because the song is this idealistic story.

In the documentary, you say, “I’m not that good at one-on-one relationships. I’m great at one-on-2,000.” What do you mean by that?

Well, not everybody’s lucky enough to say that. It’s simple. That’s one of the ways I managed to avoid having to deal with the hard work of being involved one-on-one. So I make a joke of it, but the fact is that I’ve still chosen that. To tackle having a relationship, a real honest-to-God relationship with somebody and all that it entails, it’s a conscious decision. I just don’t want to do that. Seems too exhausting.

I read that you dated Steve Jobs. And an Australian journalist once asked you, “Has it ever occurred to you that you’re the only woman in the world to have seen both Steve Jobs and Bob Dylan naked?” And you replied, “But not at the same time.”

[Laughs.] Yes, it caught her off guard because she thought she had caught me off guard.

As we see in the film, in your late 20s, you went to prison twice, for protesting the Vietnam draft. How did that experience change you?

Well, I gained 8 pounds. It wasn’t a difficult place to be. It was a rehabilitation center. In jail I was not in a leadership position, so I kind of took advantage of the [time to] rest. I didn’t have to get phone calls. I didn’t have to do mail. I bought a lot of stuff at the commissary and ate too much. And I was with my mother both times, so we had a chance to spend some time together.

What motivated you to go to therapy at age 50 and unearth your childhood trauma? Was it to rebuild your relationship with your son?

No, that hadn’t even begun yet because I was so unaware. I was so not present for so much of his life. No, I just really couldn’t go on. I didn’t want to continue with what was hampering my whole life, and had been hampering my whole life. It was unexplored territory. And I knew it would take a different kind of work from what I had always done. I had always worked around the problem with really good therapists, who kept me alive and productive and creative. I could work around it, over it, under it, but I had never dealt with whatever the it was.

And you’re bravely sharing this publicly now because you want to leave as honest a legacy as possible?

Yeah, exactly. It’s the right [time]. My family is gone. My son totally gets it. The only concern was for my granddaughter, who saw the movie and loved it. I don’t think it took so much courage; it just took a decision.

Do you feel freer now?

Yeah, and because of the nature of the recovery work [in therapy], and because of the forgiveness.

I was riveted, watching how you confronted your parents with your experience [of abuse]. You heard their denials of it. And then, there’s this footage of you with both of them toward the end of their lives. How did that work?

I will tell you one thing because it’s important: They do not remember. It’s not as though they were lying when they say that it was made up. To them, they have no memory of what went on. And I understand blocking [it], because I did that for 50 years. I wanted to remember, and it took that work [in therapy] to remember. They didn’t want to remember.

You’ve guided us through times of terrible division. Do you have wisdom for this moment, when so many people are in pain?

Mainly the suggestion I have is to live in denial most of the time, because we have to protect ourselves from our own pain. And then, whatever time you’re gonna take that you’re not in denial, do something that calls you. Go make good trouble, and try to remain a decent human being.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

If you or someone you know has been sexually assaulted, you can call the National Sexual Assault Telephone Hotline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673) or visit hotline.rainn.org.

This article was originally published on