Bustle Book Club

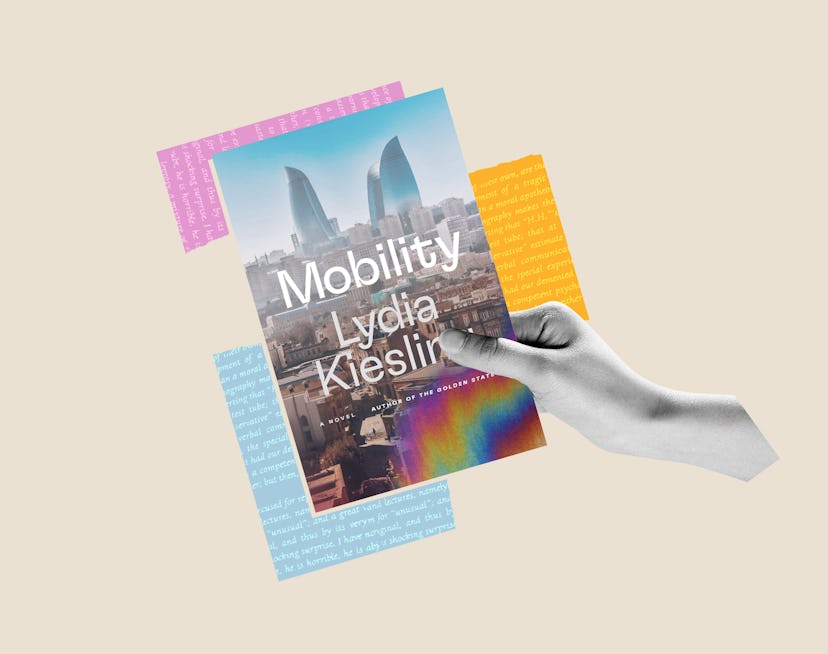

To Write Mobility, Lydia Kiesling DIYed A Writer’s Residency

The author of The Golden State made writing her second novel feel like a vacation.

Lydia Kiesling’s first book, National Book Award 5 Under 35 pick The Golden State, breathed new life into the road trip novel by giving its narrator, Daphne, a demanding passenger in Honey, her toddler daughter. To write her second book, Mobility (out now), Kiesling had to re-enact the road trip but leave the kids — she has two — at home.

Working during the closed day care, remote kindergarten days of the pandemic, Kiesling completed her first draft over a series of two- to four-day getaways at rural cabins near her home in Portland, Oregon. Kiesling’s friend, the writer Manjula Martin, gave her a valuable piece of intel: “She had gotten a residency at Hedgebrook, which is this iconic residency in Washington state. She told me, ‘Oh, Hedgebrook is doing this thing where if you live within driving distance, because of COVID, you don’t have to go through the formal long, intense residency application process’ — which I never do because it just seems really daunting and at that point would not have been worth the time.” During the shorter, sliding-scale fee program, Kiesling says, “you weren’t part of the residency, but they still gave you food and you could stay in a cabin. That was so nice.”

Beyond that, Kiesling DIYed the writers’ residency life using inexpensive AirBnBs, grocery store prepared foods, and a delicious feeling of escape. “I was so excited to be away from my home situation that I managed to bundle that time with actually writing and turn that into being excited to write,” she says. “I think that’s when the book started getting a little bit sexier, more travel-centric. I wrote more about being out in the world.”

The result was Mobility, a Jonathan Franzen-esque social novel about climate change that’s way more fun than it sounds. The book follows Bunny Glenn: foreign service brat, calorie counter, misbehaving wedding guest. Bunny’s hunger for validation and her interest in women’s empowerment — along with her childhood experiences visiting her dad, a diplomat working in the oil-rich Caucasus region — make her a model employee of the fossil fuel industry. Despite her best efforts to avoid politics, politics comes for her.

Below, Kiesling talks cabin life, researching the oil and gas industry, and writing advice to ignore.

On what she looks for in a writing cabin

Writing Mobility, I looked for whatever was the cheapest cabin that was separate, that wasn’t in someone’s house. Two of them had a composting toilet, and one of them had a porta potty. The porta potty I really don’t recommend. It was in the woods, and it was really dark, and it was so creepy. That one also had a big washtub that also served as a bathtub that you could fill with hot water. I just peed in that. I was too scared in the night to go and pee in the porta potty.

But there was one I stayed in that was a tiny house cabin, which someone clearly put their heart and soul into. I slept in a treehouse-feeling loft. And it was very cozy and the bathroom was inside and not composting. It was definitely my favorite one. The thing to do is you get prepared food from the grocery store or a box of fast-food chicken. And bread that you can just tear off. There’s no cooking in cabin life.

On researching to write a character who works in oil and gas

I watched YouTube videos of different people from oil companies, and I found a particular small Texas family-owned oil company. There were a lot of videos, like little anniversary presentations, that I could find online. I just watched videos of the patriarch talking about his company, and I read about privately owned oil companies. I read a lot of people’s LinkedIn profiles and read a lot of job listings. I was interested in a family business because that felt meatier. When we talk about toxic workplaces or just workplace generally, they become the most gruesome when they sort of pretend like it’s a family.

One thing that’s mortifying about this book, but I actually put it into Bunny too, is that I still don’t understand how any of this stuff works. I read all this sh*t for research, but if someone just sat me down and was like “Explain in detail about how the world financial market works relative to oil,” I would not be able to do that. I am also a fraud and was just doing my best with this book, and nobody should be scared that it has too much information in it.

On writing a protagonist who doesn’t care about politics very much

In 2009, I had a job very similar to Bunny’s first job at an engineering company, when she doesn’t work for an oil and gas company yet. I remember feeling “Well, I don’t want this to be my job, but I don’t know what else to do.” But that’s also the time that I started writing just for fun and as a hobby. So I was thinking “OK, well what if I didn’t have that? And what if I didn’t have some sort of outside thing that ultimately shaped who I was close to and ideas that I was close to?”

With Bunny, I looked to the parts of myself that I try to discourage from flourishing. I think a lot of that is the apathy and willful not-knowing about stuff. I think especially if you are a white millennial woman with a fair amount of privilege, the world makes it easy for you to not, to just be like “I don’t want to know.”

Energy is critical to life as we know it, and for most people, it is a daily problem. If you are lucky enough that it’s not a daily problem, if your lights turn on and your air conditioning runs, it’s easy to be like “Well, it’s magic.” But, you know, it’s not. Anything that illuminates how that came to be, I think is really important and we all need to think a lot more about it if we’re not thinking about it already.

On the writing advice she ignores

People love to talk about how you have to write every day. It’s generally known as the “butt in the chair” school of thought. I do acknowledge that sometimes you do have to force yourself, and I think it is good to have a schedule, a routine, a practice. It’s good to have that in place so that you set yourself up for success. However, for many people, a very regular and routine writing process is simply not possible, either because of family and work commitments or temperament.

So basically, look at your situation and be compassionate with yourself if you’re finding that you’re not writing for whatever reason. But also say: “OK, well this is what you want to do. You feel this calling. It’s really important to you. Where are the things that you can tweak to make it more possible for yourself? How can you get the other people in your life to support you, see you as a writer, help you get to your work?”

Because that’s also important, especially if the commitments you have are caregiving ones. You need help from other people, whether it’s a co-parent or a family member or a friend. Sometimes it’s hard to be like “Oh, I’m working on this thing. I don’t really know what it’s going to be, and it’s, like, art.” But you have to do that. You have to take it seriously for yourself in order for anyone else to take it seriously.