28

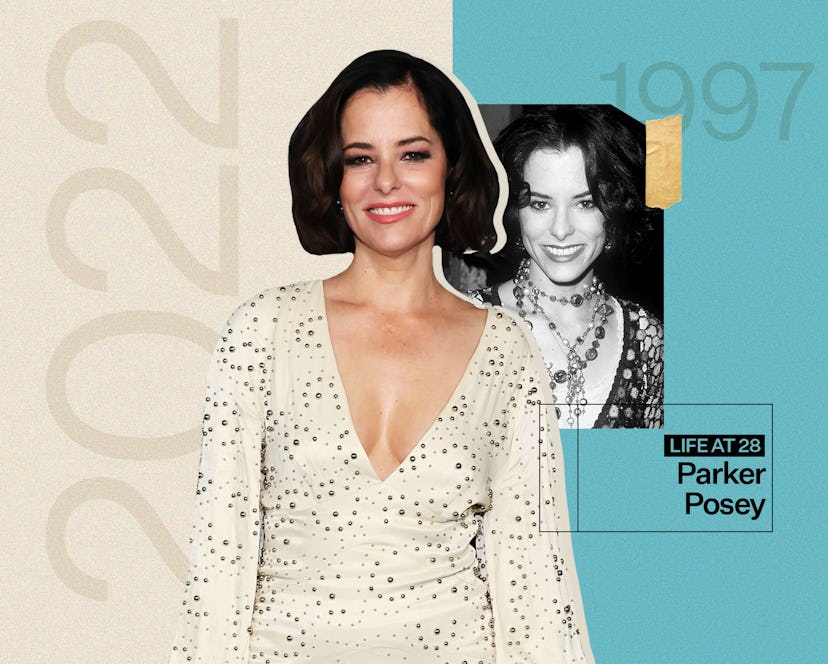

At 28, Parker Posey Swing Danced With Liev Schreiber & Ate 4 A.M. Bodega Sandwiches

Time magazine dubbed her “Queen of the Indies” — and Posey was living life to the fullest.

Parker Posey is into full-circle moments. The 53-year-old actor talks at length about making peace with herself and feeling a sense of “eternal unity,” casually mentioning everything from the dao to Frank Zappa on her circuitous path to making her point. “As you get older, you can look back and you can see the pattern,” she tells Bustle of her emotional journey to adulthood. “You can see the crazy quilt.”

Here on this earthly plane, Posey’s role as assistant district attorney Freda Black in HBO Max’s The Staircase is another full-circle moment to her life at 28, reuniting her with Toni Collette 25 years after they co-starred in the 1997 cult workplace comedy Clockwatchers. But it was hardly the only project Posey was working on at the time. Fresh off winning an award at Sundance for her darkly comedic performance in The House of Yes and the release of Christopher Guest’s now-classic theater sendup Waiting for Guffman, Time magazine dubbed then-28-year-old Posey “Queen of the Indies” in a profile that’s as laudatory as its author is confused by her willingness to book an avalanche of projects with shoestring budgets. (“If Posey keeps on making movies, she could be broke by the time she’s 30,” Time wrote in 1997, noting that she paid half her own airfare to do one film and was paid a day rate of $75 for another.)

Posey’s life as a scrappy star — not that she considered herself famous in any capacity — was all-consuming. “By the time I hit 30, I was like, ‘Oh, there’s still more?’” Posey says. “I felt like I was in such a fast car.... just speeding through my life and hanging onto parts that I was playing.” In the decades since, pop culture, too, has latched onto many of Posey’s most memorable roles, from her endlessly quotable lines in Waiting for Guffman (“I always have a place at the Dairy Queen”) to her impeccably cool fashion sense in Party Girl. Posey would likely call it another full-circle moment.

Below, Posey talks impostor syndrome, swing dancing with famous friends, and why she likes getting older.

Take me back to 1997, when you were 28. What was your life like?

I was doing a lot of traveling. I would decompress in my little tiny apartment [in New York] and just crash. Then I would talk on the phone. You’d get scripts in the mail delivered; you’d wear your pajamas outside. You’d be eating egg and cheese on a roll, and you’d have a sandwich at four in the morning.

I had the same apartment in Chelsea for 13 years. I got it in 1992 from my teacher Liz from college and I just stayed there. It was a rent-controlled railroad flat. I lived above a place called The Beauty Shop next to a Peter McManus bar that is still there. That summer, I would take one of those cloth director’s chairs and sit and talk on my cordless phone and just hang out on my “deck,” which was scaffolding.

What was a night out like for you at 28?

I remember going to Wigstock during that time. I think there was still dancing back then in New York — Giuliani hadn’t shut it all down. I would go to a night called Beaver on Thursday nights at Don Hill’s. They had this DJ named Frankie, and he would play ’70s and ’80s and ’60s dance music. I danced with Jimmy Fallon and Horatio Sanz and people who were just funny dancers. You could get picked up and twirled around! There was also a swing dance place in the East Village during that time — Sam Rockwell went there, Liev Schreiber went there. Liev was a great swing dancer.

Waiting for Guffman came out when you were 28, and it was your first Christopher Guest movie of many. Do you remember how it felt to be improvising in that environment for the first time?

When I met Chris, we talked for half an hour, and we just liked each other. It was such a unique experience, because I got to play a Southerner and I got to bring so much to it. [Improvising is] like you write a book that you carry around that no one’s reading but you. I was really nervous at first, but Chris made me feel so comfortable. He said, “We want Libby to audition for the play, and you need to pick a song.” So I picked “Teacher’s Pet” from Doris Day. At first, I wanted to sing a song by Journey. [But I decided as Libby], “Oh okay, well, I live with my aunt, because I was forced out of home. It was not a good situation.” That’s why I listen to Doris Day — I’m being taken care of by an older woman.

It spoiled me in a way, because some sets are more controlled, or you don’t trust the actors as much. There’s something just so magical about [improv] really, because you don’t know what anyone’s going to say, right? Chris was like, “I had no idea Jennifer Coolidge was going to talk like that [in A Mighty Wind].”

Professionally, 28 was a prolific time for you — Time magazine even called you “Queen of the Indies.” But what was one of your biggest difficulties or disappointments around that time?

I think it was auditioning for Reality Bites. Because I got it, but then I didn’t get it and I didn’t know what happened. But Ben Stiller and Janeane Garofalo had worked together, but I had auditioned for it and all that. That crushed me — just being told the lip service, not knowing that lip service is part of the game.

It’s weird as an actor or an artist or a maker, if you’re not being employed with what you’re doing, because you start to feel like you’re not good anymore. You get insecure and you don’t really have a place... [I had] a hard time accepting it as a business.

All I can say is it’s so much easier now to be still, and you know yourself and accept yourself more. I had a lot of fear, I suffered a lot. I was gravely disappointed. I tried to control it, but I didn’t know the Serenity Prayer.

What advice you would give your 28-year-old self?

Don’t worry so much. I can really blow things up and kind of abandon myself. Nothing’s ever over. It’s just a continual... You grow. You mature. Keep up the therapy.

I like getting older. I’m not going, “Oh my god, if I could just be young again.” I’ve always been kind of a little old lady.

What would your 28-year-old self would think of you now?

I think she would like me. I think we get older, but we always feel the same — it’s just a deepening. It’s like your roots get deeper, and your branches spread out more. We never lose our true nature, our mold; our issues are the same. There’s no escaping, there’s just awareness. So it’s like, have awareness and have courage. I think we think things are supposed to be easy, and the culture is just, I think, coming around to talking about mental health issues and grief and healing. Truth is talked about more. Do you think that, or am I just making it up?

I agree. I think we have more language to discuss things now, and it’s more normalized to do so.

When Oprah came on the scene in the ’80s, there was still so much shame around not being socially accepted or part of the status quo. Being different is so much more acceptable now. We’ve come a long way.

Did you feel different or not accepted at 28?

One of the things was, when I got famous, I started to feel like New York City is very ambitious, and it’s competitive. I started to isolate more. My close friends would come over, and we would lie on the bed and listen to music and sing songs. I would tell them stories about my work and stuff like that. I think I have a better sense I can protect myself more now, and things don’t weigh on me as heavily. That’s due to therapy. There’s imposter syndrome — I think I had that. I think I still have that.

But I like getting older. I’m not going, “Oh my god, if I could just be young again.” I’ve always been kind of a little old lady. I like to do crafts. I like to sew and make things, garden and do those things, and it’s an exciting time to be on the planet.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

This article was originally published on