Bustle Book Club

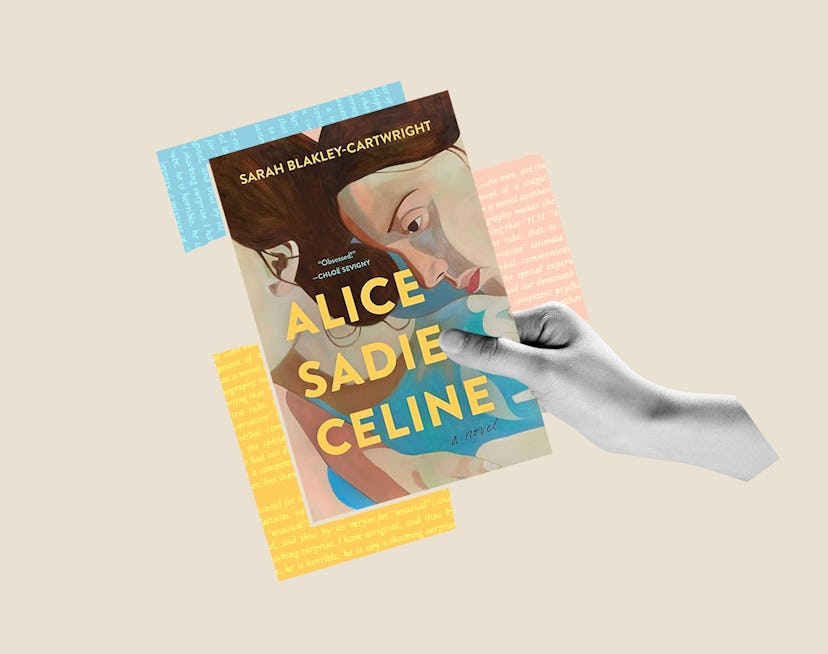

Sarah Blakley-Cartwright’s New Novel “Breaks Every Rule Of The Universe”

The author explores an unusual dynamic in Alice, Sadie, Celine.

“Obsessed!” Chloë Sevigny wrote of Alice, Sadie, Celine. “I am literally obsessed,” Busy Philipps echoed. It’s remarkably high praise, but the novel’s premise alone is enough to induce such fervor. Alice, Sadie, Celine grew out of a hypothetical scenario Sarah Blakley-Cartwright dreamt up a few years back — one so taboo, so unfathomable, that she feared it would “break every rule of the universe”: What would happen if my mother had an affair with my best friend?

Her own response shocked her. “I would hate them, I would be jealous, and I’d never speak to them again,” she tells Bustle. “Then I wanted to interrogate why I had such a visceral reaction. Why would that feel like a betrayal? Why is there this kind of parochial ownership mentality?”

These types of unusual, fraught relationships have long fascinated Blakley-Cartwright, who often finds herself seeking out stories that grapple with thorny power dynamics. So when she set out to write this novel, she decided to break every rule of the universe and focus on an affair between Celine, a famous feminist scholar, and her daughter’s best friend, the beautiful but flakey Alice. “In my life, as a consumer of art, I've often been drawn to triangles with a queer element and where young people are exploring that,” she says, citing Y Tu Mamá También as an inspiration.

Ultimately, Blakley-Cartwright had to push past her own knee-jerk revulsion, so as to approach her characters with as little prejudice as possible. “It was really important to me to show a relationship which is very liberal, but without being the jury,” she says, noting that Alice is very much a consenting adult. “That's why we read literature, to witness the mess without needing to solve it.”

Below, Blakley-Cartwright reflects on reading while breastfeeding, writing from bed, and her love of spiral notebooks.

On the novel that scandalized her:

Big Swiss is another novel of intergenerational sex between women that’s very startling, idiosyncratic, but also humanistic. It actually scandalized me, but not for the reasons that one might think. More because [Jen Beagin] manages to have these characters carting along truckloads of trauma and yet moving along at this astonishing pace. I've also read a lot of Vivian Gornick, because I have a 1-year-old daughter, and her short books and little vignettes are perfect during breastfeeding.

On ditching her desk:

The best way for me to write books has been to make it friendly for me. It's taken me two decades to understand that I don't need to write at a large imposing desk. I always felt it de-legitimized my writing to do it in bed, at a cafe, or dictated as I walk around the city. But now I finally get that I like to have life around as I write. I love to get out in the morning, walk around, see the baker, the butcher, and the seasons change.

On the benefits of not speaking the language:

Ambient sounds are good [for my writing process]. I wrote a lot of the book in Brussels because my husband was living [there], so I went there for a while. The ambient French, which I don't speak, was so helpful.

On her writing tools of choice:

I always write by hand, and some notebooks are more welcoming and others feel more rigid — but you don't know it until you hold it in your hands, or even until you begin writing. I love spiral-bound notebooks, but the white of the page and the finish of it also really matters. I like wide, saturated lines and a matte kind of grayish page that’s not too white and has a flexible spiral. That’s the kind I gravitate towards.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.