Books

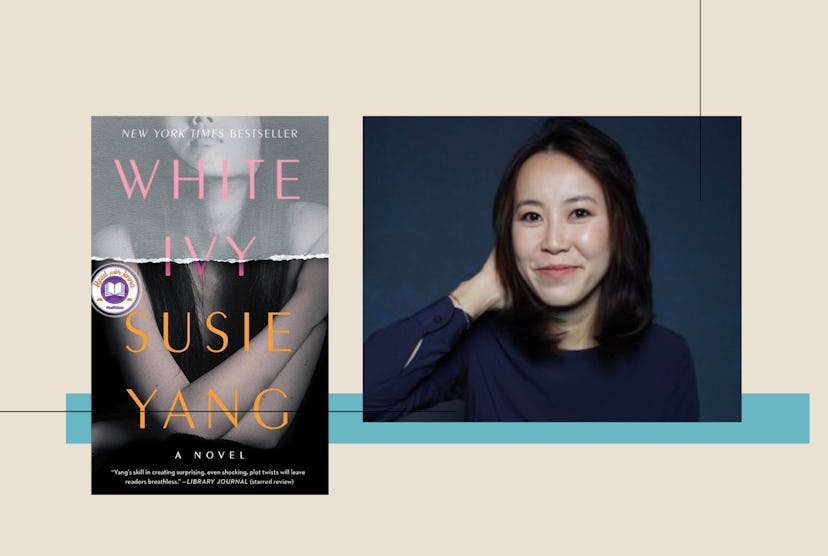

Susie Yang's White Ivy Is The Talented Mr. Ripley For The Instagram Age

The author was also inspired by Ottessa Moshfegh and Elena Ferrante's dark, complicated female protagonists.

Susie Yang loves schemers. The debut author's favorite works of literature center on sociopathic social climbers like Emma Bovary, Scarlett O'Hara, and Tom Ripley. Now, Yang has reimagined the schemer story for the modern age with White Ivy, which chronicles a young Chinese American woman's determination to worm her way into New England's upper crust. "[The Talented Mr. Ripley] was my biggest influence," Yang tells Bustle. "In terms of that specific genre — taking someone’s identity or lying about who you are blatantly — that was the most obvious example."

Americans' fascination with con artists has had a renaissance in recent years, with figures like the Soho grifter Anna Delvey, controversial Instagrammer Caroline Calloway, and the men behind the ill-fated Fyre Festival captivating audiences nationwide. You can see traces of all of these scammers in White Ivy's titular protagonist, along with the fingerprints of Yang's favorite classic works. Midway through the novel, when Ivy is reintroduced to her WASPychildhood crush Gideon, provides a good example: She'll stop at nothing to marry him. She infiltrates his social circle, reinvents herself to fit in among his blue blood crowd, and makes enormous sacrifices in the process. "At what point does that [persona] replace who you are?," Yang asks of her character's transformation. "Those are the things that I really love reading about. It’s a personal fascination."

That personal fascination has paid off. White Ivy is already being heralded as one of the best books of 2020, and it's Jenna Bush Hager's November pick for her Read with Jenna book club. And, perhaps most auspicious of all, Grey's Anatomy creator Shonda Rhimes — who's also bringing the Delvey story to the big screen — is developing the novel for Netflix. "Honestly, it still feels kind of unreal," Yang says.

Ahead of White Ivy's release, Bustle spoke with Yang about Madame Bovary, love triangles, and the allure of the upper class.

Your initial inspiration for White Ivy was to create an Asian American retelling of House of Mirth. Why was Edith Wharton a portal into this story for you?

It wasn’t just House of Mirth, but a lot of classic literature. When I was deciding what type of book [I wanted to write], I always knew that I wanted to create an antihero character. I love stories about really determined female protagonists, and [Ivy's] willing to manipulate people to get what she wants. I always knew that that was the character and story arc I wanted to write. Once I had that big vision, the first sentence in the book came to me: “Ivy Lin was a thief but you would never know it to look at her.”

Were there any "determined female protagonists" you revisited as you wrote?

I love books like Madame Bovary and Gone with the Wind. Ottessa Moshfegh has really great antiheroes. Even Elena Ferrante writes really complicated and dark women. I’m always drawn to that. So when I set about creating Ivy, I really wanted to write that kind of character — but with a background that I was familiar with being Chinese American.

It’s refreshing to see an immigrant protagonist who is, for all intents and purposes, an awful person. We get to see white men and women behave badly, but it’s rare that we get to see non-white characters do the same.

Ivy kind of breaks the model minority [narrative], right? You’re not given a redemption story. I think it was important to me that Ivy was not necessarily defined by being Chinese. I knew that I didn’t want the focus to be purely on her immigrant background. That was important to me: [to write] somebody who is relatable beyond ethnicity or culture, and whose desires are sympathetic, but not ones that we could see ourselves necessarily having. [White Ivy] was a story that was going to transcend her immigrant background.

Ivy’s motivations and struggles seem to be much more caught up in wealth and class than race. What was the inspiration behind that choice?

I've lived in so many different places [in the US and throughout Europe], so I’m used to the outsider perspective — looking in on society. So much of that [involves] the mannerisms of people you perceive to be more privileged or wealthier than you are. It has a universal fascination, especially for Ivy.

[Money is] the kind of thing that people don’t really want to talk about. Or in certain cultures, like in Chinese culture, people talk about it very openly. As an author, it was really interesting to explore people’s attitude toward money. I think it just served as a narrative device for me to explore cultural differences and different ideas of the type of privilege that exist in Chinese and American society.

Ivy falls in love with Gideon, who's a WASP. His family isn't particularly wealthy, but they have social status, which to Ivy is something to aspire to.

I love that you phrase it as "something to aspire to," because that forms the core of Ivy’s motivation. She’s always looking around her, trying to see what it is she should be aspiring to. As an author, that’s what makes exploring these families interesting. I want people to see the world through Ivy’s eyes and how she’s gleaning from the people around her what is good, what is bad, what is privileged.

This story also centers on a love triangle. Ivy is in love with both Gideon and her childhood friend Roux, who has plenty of money but isn't a member of high society. What draws Ivy to both of these men?

I wanted to show that Ivy isn’t necessarily drawn to Gideon and his family because of wealth. Roux's obviously wealthy, but Ivy doesn’t respect that wealth. She wants something beyond that wealth: the status.

Roux and Ivy have that kind of bond where they both see the world in a similar way. [For them] it’s a dog-eat-dog world where resources are finite and only so many people can get them. He acknowledges that in her, but he respects her for it. She acknowledges that in him, but doesn’t respect that.

She thinks, 'I can’t settle with somebody like that, because then that’s who I’ll be, too.' She wants to be with somebody who is more idealized and heroic in her mind. So Roux and Gideon were almost like Ivy choosing between two different versions of herself.

This interview has been edited and condensed. Additional reporting by Samantha Leach.

This article was originally published on