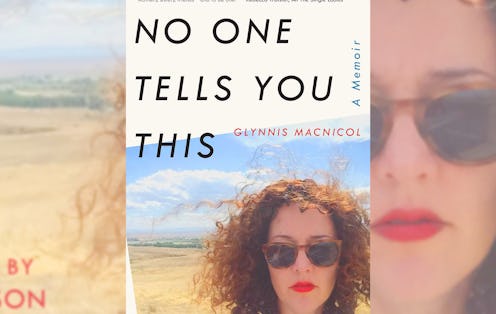

Books

This Memoir Gives A Fresh Perspective On Life As A Single, Childless, Over 40 Woman

On the eve of her 40th birthday writer Glynnis MacNicol faced a dwindling clock, alone and shackled by dread. The memory of the night serves as the opening paragraph in her new book, No One Tells You This, where she writes:

“I sat alone at my desk on the seventeenth floor of an office building in downtown Manhattan, unable to shake the conviction that midnight was hanging over me like a guillotine. I was certain that come the stroke of 12 my life would be cleaved in two, a before and an after: all that was good and interesting about me, that made me a person worthy of attention, considered by the world to be full of potential, would be stripped away, and whatever remained would be thrust, unrecognizable, into the void that awaited.”

No One Tells You This is MacNicol’s exploration of that “void.” The book unrolls a warm-yet-earnest chronicle of her first year as a woman living childless and unmarried over the age of 40. In her writing, MacNicol reveals herself as savvy, self-consciously feminist, and deeply troubled by her inability to fully shake the culturally-imposed shame attached to single women "of a certain age." She confesses this ambivalence, which becomes a driving force in her book, on the very first page: “It was ridiculous. Deep down, I knew it was ridiculous. However, knowing this did not keep me from anxiously glancing at the clock out in the hallway as if the hands on it were actual blades.”

Yet when the clock does strike, signaling she has officially turned a year older, MacNicol finds none of the horror she anticipated. “I woke feeling victorious. This was unexpected," she writes. Yet, confronted with the "rest of her life," she also feels a sense of bafflement. Having passed the mythic threshold of middle-age, after which women are expected to "give up" on hopes for marriage and family, how was she to define her story?

“It was ridiculous. Deep down, I knew it was ridiculous. However, knowing this did not keep me from anxiously glancing at the clock out in the hallway as if the hands on it were actual blades.”

Such questions are challenging at any age, but, as a childless woman over 40, MacNicol finds herself particularly bereft of any cultural or personal role models. Like many women of her generation, MacNicol grew up with a stay-at-home mother, whom she described to Bustle as a "true child of the 1950s," and "a brilliant woman who chose a conventional life." Having married at 25, forgoing a professional career to stay at home with her children, MacNicol’s mother embodied many of the traditional gender roles things her daughter would come to reject.

"I knew I didn’t want what she had," MacNicol tells Bustle. "But I also had no one to point to in my life as an example of what I did want."

Born in 1974, the author represents a generation of women at a crossroads. Growing up, MacNicol sought many of the accolades associated with emerging ideals of a modern, “liberated” woman: education, career, financial independence. Yet the pull towards marriage and family remains strong, notes MacNicol, who described feeling, “as if I’d been living in a room filled with doors marked BOYFRIENDS, MARRIAGE, BABIES, FAMILY, and everyone but me was exiting through them. I was constantly being left."

“I knew I didn’t want what she had. But I also had no one to point to in my life as an example of what I did want.”

Watching others cross these thresholds, MacNicol is struck by the easy erasure of her own narrative. Without any of the culturally-recognized milestones of marriage, pregnancy, and children, her life trajectory feels invisible and amorphous. “The problem was the encroaching sense that I had somehow stepped outside of ritual and was always going to be a guest star, forever celebrating the milestones of others without ever starring in my own. What cultural markers were there for women other than weddings and babies?" she writes.

No One Tells You This by Glynnis MacNicol, $16.92, Amazon

MacNicol is no hapless victim; she repeatedly asserts her complicated but genuine love for the independence afforded by her single life. She is not without romance, either; she weaves in and out of several relationships over the course of the book. Yet as she watches her friends transition into family life, MacNicol cycles through private feelings of loneliness and self-doubt about her enduring singleness. She writes, “Was it always going to be like this? I wondered. This roller coaster of doubt and elation? Was this the price and the reward for not committing to some larger, more established idea of life?”

Even from her perch in a progressive New York City neighborhood, MacNicol finds herself bombarded by cues that she is fundamentally “missing out” by forgoing marriage and children. Strangers and friends alike offer her unsolicited condolences for her singlehood, while others, including total strangers, accost her with their questions, demanding an explanation for her bewildering lack of spouse and children. The need to constantly defend one’s basic existence can be exhausting, says MacNicol. “There are two big stereotypes about unmarried women,” she tells Bustle. "Either we’re selfish — too selfish to commit to a husband and children, too selfish to take responsibility for others — or we’re the object of pity, as if we’ve failed or been rejected from the one thing that could possibly make us happy.”

MacNicol’s life, and her book, are a clear refutation of both. Her life is rich with relationships, and dense with responsibility. As her large but tightly-knit community of girlfriends move into their 30s and 40s, MacNicol is intimately involved in their own transitions to marriage and parenthood. She “gives away” her friends at their weddings, toasting with tearful joy the women who comprised her chosen family in New York. Despite not having her own children, she helps many of her friends through their own fertility battles, pregnancies, and births. She is a devoted aunt, helping her sister, a single mother, raise three young children. She also shoulders much of the burden of caring for her aging mother, whose struggle with Parkinson’s disease took a drastic decline in MacNicol’s 40th year. “I did a lot of caregiving that year,” MacNicol says. “It’s ironic, how sometimes being single means you give more, not less, to others — the assumption is that you don’t have children or a spouse, so you’re the available one.”

"It’s ironic, how sometimes being single means you give more, not less, to others..."

Despite her intense involvement in the lives of her loved ones, however, MacNicol must still grapple with the idea that the bonds of marriage and parenthood are still perceived as superior to all other bonds. “People ask me all the time: Don’t you want children of your own?” she says. She’s not immune to the pressure; she admits to moments of feeling lonely, tired, and in want of a committed partner. Meanwhile, her social media feeds offer her constant glimpses into the seemingly-picture-perfect bliss of married life. “We’re always drawn to the clearest articulation of what we think we lack,” she writes. “Whenever I encountered that husband-shaped hole in my apartment, I needed only to open my phone and I could find its cutout there, in exact proportions, in someone else’s life.”

Yet her 40th year brings many picturesque moments, too: a whirlwind trip to Iceland, a cross-country road trip with a friend, a cruise along the French coast. At each turn, MacNicol reflects that it is her singleness that enables her often-impulsive escapades. She also finds herself an object of envy to many of the Instagram-polished mothers who haunt her feed. MacNicol fields confessions from married friends: “I wish I’d been braver about not getting married,” says one. Another: “You make me want to be single again.” Many of them advise: “Don’t ever have kids.” The irony is not lost on MacNicol. “The idea I could be a source of envy was still something of a revelation. On paper at least — single, childless, 40 — continued to be the definition of the thing most women believe they should avoid at all costs," she writes. Yet the exhaustion and pent-up frustration of her married, child-rearing, “successful” friends are, to her, a sign that women are still beset with impossible pressures. “I think one of the most punishing things about the narratives often attached to women's lives is that we talk of happiness as if it's a permanent solution or state, attainable by marriage or children.”

At each turn, MacNicol reflects that it is her singleness that enables her often-impulsive escapades. She also finds herself an object of envy to many of the Instagram-polished mothers who haunt her feed.

This is perhaps the most important of MacNicol’s insights: mainstream culture’s failure to women as a whole — married, or not. While single women are made to feel incomplete for not opting for partnership and parenthood, women who choose to become wives and mothers inherit a new set of perfectionist ideals. Everywhere, broadcast images of the “perfect wife,” “perfect mother,” and “perfect modern women” compete for their limited, increasingly-stretched energies, driving many to burn-out or secretly-harbored shame.

“Every woman I knew seemed to think she was failing in some way, had been raised to believe she was lacking, and was certain someone else was doing it better,” writes MacNicol, “Had been told never to trust her own instincts. Taught to think of life as a solution when “done right” when in reality we existed in a kaleidoscope made of shades of gray, able to be very happy and very sad all at the same time.”

It is this nuance that finally sets MacNicol free from her own cycle of doubt, and her fears of future regret. “The most frequent question I get is, 'Aren’t you afraid you’ll regret not marrying, not having kids?'” she tells Bustle. "But what kind of way is that to live a life?” Realizing, as she writes, that “life [is] not a savings plan,” MacNicol at last gives herself permission to embrace her own instincts and desires. "I am alive today," she says. "I am going to live to my fullest now."