I am a 27-year-old, unmarried woman, which, by the religious attitudes of my youth, should mean that I'm not yet a sexual being. Except, of course, I am. I’ve been a sexual being for most of my life, whether I embraced that reality or not. I wasn’t really taught to.

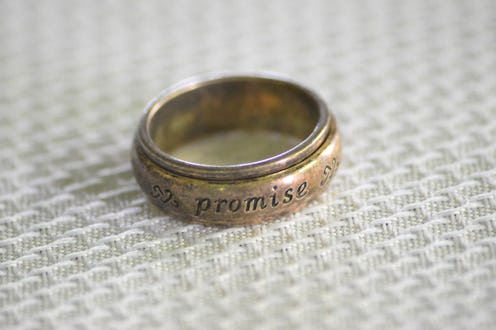

I grew up as an evangelical Christian in the shadow of Purity Culture. The "True Love Waits" movement was not new, but still popular; young stars of similar age, like the Jonas Brothers and Selena Gomez, were spotted with purity rings. It was a few years after the book I Kissed Dating Goodbye became a smash hit, advocating for no sex before marriage and outright dismissing the concept of dating as a means to find a spouse who might be compatible for the long haul.

I absorbed the “dangers” of lust, premarital sex, and sexual fluidity through in the lens of weekly Christian teachings — conveyed in black and white, before I knew the million shades of grey through which those lessons could actually be interpreted. But even after I’d outright rejected these ideologies, the repercussions have seemed to follow me anyway.

It took me years to stop policing my sexuality, and all the shades of it that turned up in my day-to-day life — from minimizing the appearance of my breasts in form-fitting clothes to accepting the high sex drive I once completely buried. After nearly a decade of issues with my pelvic floor, which affected both my enjoyment of sex and urination, my OB/GYN told me that my the muscles were too tight and not relaxing properly; I was prescribed pelvic floor physical therapy.

The term “vaginismus” is going out of style in the medical community, but this involuntary contraction of the vaginal walls, causing pain and discomfort, has frequently been linked to religious upbringings. I’ll never really know how much of my pelvic floor dysfunction was caused by sexual repression and internalized beliefs that I was trying to untangle and shed.

What It Means to Be Repressed

The phrase “sexual repression” is fairly self-explanatory. “It means repressed sexuality — but the ways it can manifest itself are varied, and it can result from a fair number of different experiences or backgrounds,” Carol Queen, PhD, a sociologist, sexologist and founding director of the Center for Sex & Culture, tells Bustle.

Queen says you can also think of sexual repression as a “powerfully-felt restriction, often inculcated by family or community, and based in shame, disgust, or fear of one’s own sexual interests” and potential. “This could mean that a person might otherwise enjoy a sex act that, because of repression, they will not consider,” she says. “It might mean that certain kinds of sex — or sometimes all sex — evoke negative feelings, even if the circumstances surrounding the sex are not problematic.” Think: A partner, who you love, may bring it up in a respectful atmosphere and only want to do it in a consent-based way, but you feel guilt, shame or anxiety. “If the “No!” a person feels in an otherwise positive context is strongly colored by shame, disgust, or fear, repression might be the culprit,” Queen says.

Some people have been taught that abstinence is the answer. Karla Ivankovich, PhD, a clinical counselor in Chicago, tells Bustle that “saving yourself” has historically been seen as best way to keep yourself physically and emotionally safe, even if few people actually practice it. (According to statistics from the Guttmacher Institute, some 90-95% of people report having sex before marriage these days.) As Ivankovich says, even for those who are trying to abstain, sexual thoughts may lead to guilt and fear. “These emotions have been linked to depressed mood,” she says.

As I determined on my own journey toward dating, sex and (eventually) long-term love, it is harder than ever to justify abstaining from determining long-term compatibility through sex and dating — especially among a generation delaying marriage in favor of playing the field, discovering who you are and who you want to be as a partner. Ivankovich says that even if a person does abstain successfully, they may experience guilt even from just questioning their beliefs.

It’s hard to ignore the importance of embracing your sexuality in a healthy and ethical way. Testing those core facets of a relationship can only strengthen your choice of a marital partner; one can only speculate, but it appears Joshua Harris, the author of I Kissed Dating Goodbye — the uber-popular evangelical romantic manual that shunned the idea of trying on different partners via sex and dating, as well as condemned non-straight sexual orientation — may have learned this the hard way. He separated from his wife earlier this summer; he said he’d had a radical change of beliefs. (Bustle reached out to Harris for comment, but did not receive an immediate response.)

What Happens After You Abstained?

Linda Kay Klein, author of PURE: Inside the Evangelical Movement that Shamed a Generation of Young Women and How I Broke Free, says Purity Culture reinforced some incomprehensible practices about waiting. “The rules abruptly change as soon as you get married,” she tells Bustle. “Suddenly, women who have been told their whole lives that they will never be loved by a good Christian man if they don’t shut their sexuality off are now told that if they want to keep the love of that good Christian man, they have to turn every part of their sexuality on like a light switch.”

Many are disappointed when this does not happen, because “bodies and brains don’t work this way,” she says. “Sexual repression sometimes leads to a physical inability to have sex when the person wants to,” Klein says. “Men struggle with erections; women experience a physical tightening of the vaginal muscles that makes entry impossible.”

Meanwhile, men who have been told their whole lives that it's wrong to have sexual thoughts about a woman are now told that in order to be “real men,” they have to be the sexual leader, says Klein. “Hungry, and somehow knowledgeable about something they were told to never think about,” she says. “It’s presented as a formula: If you repress your sexuality before marriage, you will have a hot, wild sex life after marriage... If my 12 years of interviews are any indication, this is very unlikely to lead to a hot, wild sex life.” It’s also detrimental to link someone’s sexuality to concepts of self-worth. It is the root of shame.

Earlier this summer, Harris issued an apology for that which he used to advocate. “I have lived in repentance for the past several years, repenting of my self-righteousness, my fear-based approach to life, the teaching of my books, my views of women in the church, and my approach to parenting to name a few,” Harris said in an Instagram post dated July 26. “But I specifically want to add to this list now: to the LGBTQ+ community, I want to say that I am sorry for the views that I taught in my books and as a pastor regarding sexuality. I regret standing against marriage equality, for not affirming you and your place in the church, and for any ways that my writing and speaking contributed to a culture of exclusion and bigotry. I hope you can forgive me.”

Queen says these sorts of beliefs can manifest as a result of sexual repression. “A repressed person may seem and feel out of place in many contemporary communities and subcultures that value sexual exploration or enjoyment,” she says. “Repression can be linked to traits like homophobia or transphobia, or extremely rigid gender ideologies. When repression is widespread, sexual and gender minorities can be treated badly.”

In terms of other toxic beliefs, sexual-shaming cultures often place a woman’s value on her purity instead of placing value on her personhood, Klein says. Men have reported struggles with “moral confusion,” which can lead to “immoral, and even illegal” action, Klein says. “Having repressed all physical desire, uniformly categorizing it as ‘sin,’ they can’t — or don’t — differentiate between healthy sexuality and sexual harassment, assault or even rape,” Klein says. “So when the repression dam breaks, any one of these things can come spilling forth.”

Religion's Role In Repression

Queen says that religion can play an “enormous” role in sexual repression; saving oneself is not unique to evangelical Christianity either. It is a facet of virtually all “conservative religions,” like Muslim, Catholic, Jewish faiths, among others, says Queen. “But it doesn’t always have to [shame],” says Queen. “And I want to be careful to differentiate conservative religious teaching about sex from the kind of repression that instills shame." Queen says it’s not believing certain groups are “ungodly” or “unholy,” but rather a person believing one’s self is not OK because of sexual desire.

Ivankovich says there can be lifelong impact of holding onto reinforced beliefs of who your “Ideal Self” should be — sexless, only liking certain types of sex, only liking certain sexes, etc. Sometimes, this shift comes to a head at marriage, per many conservative cultures. Sometimes, it’s a shift a single person wants to make, but can’t figure out how. “For a person to achieve that state of self-actualization or becoming your best, truest self, your Ideal Self and your Real Self need to meet and fall in love,” she says. “They must be in a state of congruence.” But if a person has been taught to reject their Real Self, it’ll be hard to ever get to ever feel fulfilled — not just romantically, but personally.

Overcoming Sexual Shame

Repressed shame was a somewhat strange entity for me. I didn’t realize the impact it was having on my relationships at first, attributing my slow-warmup to sex and dating during my teens and early college years as indifference, not the avoidance it actually was. Deep down, I was dealing with an existential crisis about whether my faith could coexist with my sexuality.

Sometimes, the volcano of feeling and (over)thinking that would occur after intimacy felt like an out-of-body experience; I analyzed it externally, as I experienced it internally. I’d sought to avoid guilt and shame, so prevalent during my childhood, for most of my adult life —but there it was, arising after getting physical, even though it did not jibe with my evolved belief system. Eventually, a therapist helped me ask the right questions of myself, and I developed a healthier view of sexuality, as well as healthier relationships; I finally had the building blocks for them.

The number one most important thing a repressed person can do is recognize the signs and learn that there are alternatives, Queen says. She says being part of a sex-positive community can matter to some, or an LGBTQ community. Exploration through books, blogs, and so forth, or changing from a conservative house of worship to a more sex-friendly or progressive one may help. And if you're able to, seek a therapist. “Many sex therapists are familiar with this set of issues and the effects they have on peoples’ happiness and satisfaction,” Queen says.

Klein suggests repressed men and women explore their sexuality on their own using the medium that most inspires them — any medium. For example, a visual artist recently came to Klein and told me that she can’t kiss somebody without intense anxiety. “Channeling the healing work of Rev. Lacette Cross, founder of Will You Be Whole Ministries, my ‘homework’ for her was to create a series of art pieces, such as a collage, answering the question ‘What does sexy mean to me?’”

The artist just reported the results to Klein. “She told me that she has been doing her homework,” she says, “and just had her first kiss without a panic attack.” A tiny step for most; leaps and bounds for someone who’s finally getting to experience the smallest slivers of sex positivity.