Books

Women Brothel Owners, Prosecutors & Burlesque Dancers Get The Spotlight In Karen Abbott's Books

The first time you pick up one of Karen Abbott’s books, you might find yourself double-checking the cover to make sure you’re not reading a novel. The pacing and tone will pull you in like a bestselling thriller, but the dozens of pages of citations and notes at the end of the book will quickly inform you that this is indeed a work of nonfiction. Though not a degree-holding historian, Abbott is a pro at captivating audiences with events of the past.

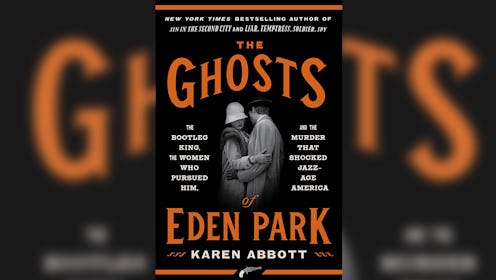

Abbott’s newest book, The Ghosts of Eden Park, centers on misremembered or forgotten figures of history. In this case, the figures are prosecutor Mabel Walker Willebrandt and George Remus.

Willebrandt was only the second woman to be appointed to U.S. Assistant Attorney General, and the first to serve for an extended period of time. She did extensive work to uncover shady dealings in nightclubs in the 1920s, and despite being personally opposed to Prohibition, her job brought her head-to-head with Remus, the so-called "King of the Bootleggers." Incredibly rich and protected by bribes and corruption, Remus was known to casually carry hundreds of thousands of dollars on his person at a time when the average median income was $1200 a year. This was a man who felt he was above the law, and Willebrandt wanted to prove that wasn’t the case. Though much of the book is focused on Remus and his catastrophic relationship with his ill-fated second wife, Willebrandt is the true star of Ghosts of Eden Park. She pushed her way through the unjust social standards of the time to be appointed to one of the highest legal posts in the country and used her status to improve conditions for women working in the legal system.

Abbott has a knack for telling the stories of incredible women in history. Her first book, Sin in the Second City, is the tale of two sisters who created a clean and comparatively safe place for sex workers to live and work in turn-of-the-century Chicago: The Everleigh Club. In Sin in the Second City, Abbott painted a full picture of the moralists and journalistic scare tactics that were at play at the time and continue to this day. The sisters had questionable, mysterious pasts, but they did whatever they could to keep the women they lived and worked with healthy, happy, and surprisingly independent for the time. The Everleigh Club could have been a historical landmark, but since it lacked fair documentation of its status, it was demolished. Long forgotten for their fascinating role in Chicago history, the sisters were a compelling topic for a debut.

In her next book, American Rose, Abbott shifted her focus to the burlesque dancer Gypsy Rose Lee. At the time of the book’s release, Lee was mostly known by the ahistorical 1962 biopic, Gypsy, based on her memoirs. Abbott dug deeper and uncovered a tale of childhood abuse and a woman who was never allowed to feel truly safe or loved despite her reputation as a nationally famous performer. Her sister, the actor June Havoc, and Lee were pitted against one another and forced into performances in hopes of gaining their mother’s affection. In Abbott’s care, a story became a heart-wrenching tale of a manipulative and abusive stage mother and the daughters who, against all odds, managed to survive her.

In her 2014 followup, Liar, Temptress, Soldier, Spy, Abbott turned her attention to the Civil War and focused on four disparate women who worked undercover two for the Union and two for the Confederacy. Abbott cites the inspiration of the book as her bafflement when she visited the American South and realized, due to the presence of confederate flags and offensive bumper stickers, [where did she say this?[ that there is still a group of people that continue to actively mourn the success of the Union. In her research, she began to realize that this was the American war in which women initially seemed to become active after decades as docile bystanders and victims to its ravages. Abbott showed readers the role a handful of women played in “the bloodiest war,” a history that has until recently all but excluded women entirely.

Indeed, the women of Abbott’s books lived through all different kinds of experiences. While Remus' wife Imonen lived a life of luxury, it all came crashing to a halt when the couple divorced. For the Everleigh sisters, their comparatively high standards for their profession became exactly the thing that brought them to disaster. Willebrandt achieved great success in the legal field, but was forever limited by her gender and was continually passed over for promotions despite having played a major role in prosecuting a number of bootleggers. Gypsy Rose Lee and her sister both achieved some notoriety in their fields as working artists, but they failed to ever gain their mother’s love. The double-edged sword of success for women under the patriarchy is a recurring theme of Abbott’s works.

Still, Abbott does not glorify the women she writes about. At best, in the case of Gypsy Rose Lee and Mabel Walker Willebrandt, these are morally complex women whose activities were only occasionally self-motivated. Yet, her attention to fleshing out and humanizing women is all the more impactful for its rarity among historical texts. The novel-esque pace of Abbott’s books will attract fiction readers, but her research, carefully annotated at the end of each book, show an attention to accuracy seldom seen, even in the realm of narrative history.