Books

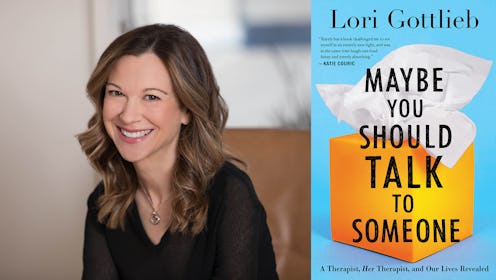

This New Book Is All About Therapy — From The Therapist's Point-Of-View

According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, 43.8 million adults experience mental illness each year. Yet, according to Lori Gottlieb’s new book — Maybe You Should Talk To Someone, out now — only around 30 million Americans seek therapy, yearly. It’s no secret that there’s a mental health crisis in the United States, so why are so many people not getting help?

“I think that a lot of people feel like they can’t justify their pain — they feel like pain has to have a justification,” says Gottlieb, a psychotherapist who also writes the weekly “Dear Therapist” advice column for The Atlantic. “People think: well, yes I’ve been feeling sad or depressed, and I’m struggling a bit. But look at all the good things I have around me. I don’t really have a reason to be depressed. I have good friends, I have a nice family, I have a great job: what’s my reason? How do I justify the feeling that I’m having?”

Except, you don’t have to justify your feelings, Gottlieb tells Bustle, nor do you have to rank your feelings on some sort of global, social spectrum of suffering. As she writes in Maybe You Should Talk To Someone, there’s no hierarchy of pain, and suffering shouldn’t be ranked.

“I think that a lot of people feel like they can’t justify their pain — they feel like pain has to have a justification."

“We do with our emotional health what we don’t do with our physical health,” says Gottlieb. “If you were experiencing [even mild] chest pain for example, you probably wouldn’t wait until you have a massive heart attack to get that checked out. But with our emotional health unless we’re having a major crisis or our depression spirals out of control, people are really reluctant to seek help.”

Maybe You Should Talk To Someone is all about seeking help — taking readers into what goes on behind the notepad and in the lives of therapist themselves. And it might surprise you to know: even therapists go to therapy. Just like Gottlieb did, in the wake of a breakup that left her confused, furious, and heartbroken. “If the job of being a therapist is hard, the job of seeing a therapist is doubly so,” Gottlieb writes in her book — the book, she admits, is her most personally revealing yet.

In Maybe You Should Talk To Someone, Gottlieb shares the stories of her patients alongside her own. They’re struggling in their marriages, navigating cancer, facing old age, and more. Before introducing her readers to any of her patients, she writes: “You may not like any of the patients, but you’ll certainly recognize yourself in aspects of them.” It’s that likability factor that Gottlieb says she worried about at the beginning of her career as a psychotherapist: How can you possibly spend time each week talking intimately with someone, if you don’t even like them?

“When I was training I worried about that: what happens if I don’t like the people who come to see me? I didn’t know what it would be like to be a therapist,” says Gottlieb. “My supervisor told me, ‘there’s something likable in everyone, and it’s your job to find it.’ And I said, ‘yeah, yeah’ but not everyone.’” Gottlieb admits her initial skepticism — and after the first impressions some of her patients make in the book, I’m not surprised.

“But what [my supervisor] meant by like was that it’s very difficult to get to know someone on a deeper level — their histories, their childhoods, their vulnerabilities, their shames, their secrets — and not come to like them in some way,” Gottlieb says. “You find that human connection with them, you develop a fondness for them. That doesn’t mean out in the world this person might necessarily be someone you choose as a friend, but it does mean that you have real respect and affection for the person.”

"It’s very difficult to get to know someone on a deeper level — their histories, their childhoods, their vulnerabilities, their shames, their secrets — and not come to like them in some way."

It’s that deeper connection that is missing on many levels in culture today. And not only do people need it socially, as Gottlieb explains, they actually crave it neurologically too. “I think the therapy room, sadly, has become one of the few places where you can sit face-to-face with another person for fifty minutes. You can hear them breathe. There are no screens. Nothing is going to buzz, or ping, or disrupt you and your attention from each other,” she says. “That’s a really important experience neurologically. It lowers your heart rate. It’s a completely different physiological experience from the constant interruption we’re used to. We’re not used to the quiet anymore, even with ourselves. And so we have trouble being alone with ourselves and we have trouble being present with others.”

She shares an all-too-true joke a colleague frequently makes about the internet, calling it the most effective, short-term, non-prescription painkiller out there. And — as evidenced by some of her clients — she’s not wrong.

“I think that so many people are suffering alone and feel very isolated in their experience,” says Gottlieb. “They’re trying to kind of trudge through something that could be helped so much more effectively by doing a little preventative work instead of waiting for something really serious to happen. You can tamp down your feelings, but your feelings are still there. You can’t actually will them away. And if you try to suppress them they will only get bigger.”

Still, there’s a good bit of humor — if not always laugh-out-loud, certainly good natured — in Gottlieb’s writing. She’s honest, and perhaps even lightly self-deprecating about her own struggles, and finds the lightness in her clients where they’re open to it. As heartbreaking as many of Gottlieb’s clients’ stories are, you will laugh when reading her book.

“I was writing about the ridiculousness of the human condition — and I don’t mean that in a condescending way,” Gottlieb says. “I mean that being human is kind of a funny thing. It’s hard. Our pain is not funny, but the ways that we tend to shoot ourselves in the foot, the ways that we can’t see the bling spots that everyone else can see about us, the ways we could get ourselves out of some difficult situations if we were able to see ourselves more clearly — all that is funny. But then there’s a lot of pain: it’s just hard to be a person in the world. I tried to capture both of those aspects of the human experience. What I tried to do in the book was write this real experience so that when people read it they’d say: “Oh, that’s me too.” They might not have the exact same situation [as Gottlieb’s clients] but they can recognize themselves those patterns and behaviors. And hopefully, they can feel less alone. I think that’s the beginning of the conversation that I tried to start.”