Books

L.E.L. Was Called "The Female Byron" During Her Lifetime — So Why Don't We Know Her Name?

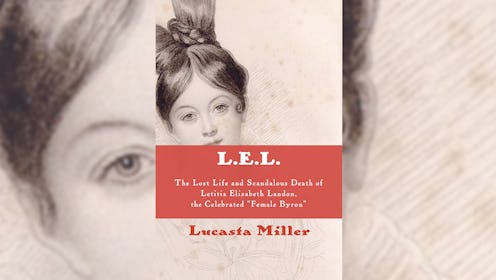

During her lifetime, English poet and novelist Letitia Elizabeth Landon was known by many names: Her nom de plume, L.E.L.; the "female Byron"; the "Sappho of a polished age"; even London's new "Corinne." Yet today, few recognize any of her identities, let alone her work, which was lauded during her time. What happened to Landon, and how did her story get lost? That is the mystery that British literary critic and author Lucasta Miller unraveled in her new book.

L.E.L.: The Lost Life and Scandalous Death of the Celebrated "Female Byron" chronicles the scandalous life, short but brilliant career, and mysterious death of Letitia Elizabeth Landon, one of the most notable writers of London's Romantic Age in the 1820s. During her brief tenure at the top of England's literary pyramid, L.E.L. was celebrated for her daring, her romanticism, and her passion, and her fans included the Brontës, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Edgar Allan Poe, Heinrich Heine, and Virginia Woolf.

However, while her contemporaries like Byron, Keats, and Shelley have become required reading in the centuries since their deaths, L.E.L. has been largely forgotten by the literary establishment. It wasn't until recently that the poet was "rediscovered." But why? "My power is but a woman's power / Of softness and of sadness made," L.E.L. wrote in her poem "The Golden Violet."

The same way many great female writers are disregarded by historians and critics for decades or centuries at a time, L.E.L. became a casualty of her time and her gender.

Landon, by all accounts, led a scandalous life. She had an ongoing affair with her married mentor, William Jerden, the editor of the Literary Gazette. In secret, she gave birth to three of his children, none of whom remained in the care of their parents.

She was also motivated by money, and sought both fame and fortune for her writing, an unusual desire for female poets at the time. Her persona was carefully designed to earn her the cult status of Byron or Shelley or Keats, but she introduced L.E.L. to a changing world. At a time when the moral climate of Great Britain was becoming more restrictive and censorious than ever, she was doomed.

But before her inevitable downfall, Landon and her poetic persona flourished. Born in London at the turn of the 19th century in 1802, she published her first poem when she was still a teenager. By 1821, she was the unknown author of a popular weekly poetry column in the Literary Gazette, which she signed with three simple letters: L.E.L. It was a pseudonym and an identity. "The persona she created in 1821 was a product of the culture wars that were gripping the reading nation that year, as what we now call Romanticism came under increasing attack from the moral majority," writes Miller.

L.E.L. existed in a moment in history that is hard to define, one that is often referred as a "strange pause" and "indeterminate borderland." It was also a strange time in literature: the end of the Romantic era, and the beginning of the Victorian period and the literary reign of Charles Dickens. The world around L.E.L. was changing and becoming a more inhospitable place for women.

When she revealed her true identity in 1824, Landon publicly relished her stardom. Her first novel, The Improvisatrice, became a bestseller, and the author became a staple in London high society. In the same same year that Byron died, Landon was reborn the "new Byron," a title bestowed upon her by her mentor, editor, and lover, Jerden.

But her private life would ultimately destroy her career. By the time she published The Improvisatrice, she was already mother to the first of three secret love children fathered by Jerden, and rumors were starting to circulate about her promiscuity. This delicate balance she struck between her real life as Letitia Landon and the one she performed for the public as L.E.L. was often reflected in her writing, which didn't shy away from the subject of fame and facade. “I lived," wrote L.E.L., "only in others’ breath."

So too would the poet, and the woman, die. After the Sunday Times published an exposé written by a cleaner who described sexual acts he witnessed Landon and her lover engaging in, L.E.L.'s career and Landon's reputation was ruined. Although she denied the claims, the damage was done. She was shamed by her male peers and lambasted by the same critics who once sang nothing but her praises. She was, by every measure, a fallen woman.

Landon fled London, and in an attempt to leave her ruined literary career and her tarnished reputation behind, married a British colonial official in West Africa. Eight weeks after arriving on the new continent, Landon was found dead in her room in Cape Coast Castle, a bottle of pills clutched in her hand. She was 36 years old. The cause of death was shrouded in mystery, but Miller argues it was death by suicide.

Landon's work was swept under the rug by those who desired a clean slate after an era of supposed sin. "The Victorians wanted to forget L.E.L., and yet she haunted them," writes Miller. "She was the scapegoat who the literary profession had to eject in order to recast itself in a more respectable mode. An entire culture had been complicit in her rise and fall."

L.E.L. is an luminous and engaging literary mystery supported by thoughtful and exhaustive research. It is also a necessary story about English literature, one that cannot be overlooked. As Miller writes, "Without L.E.L., we cannot fully map the contours of 19th-century literature. She is the missing link."