Books

This Modern Classic About Migrant Children Is An Essential Read For All Americans

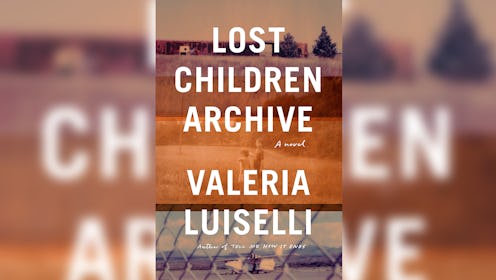

In 2014, as the humanitarian crisis at the southern border grew worse, novelist Valeria Luiselli volunteered to translate for Latin American migrants attempting to enter the United States. Her experience inspired her 2017 nonfiction book Tell Me How It Ends: An Essay In 40 Questions, a powerful and damning examination of the disparity between the so-called "American dream" and the experience of the thousands of undocumented children that arrive at the country’s border seeking it out every year. Lost Children Archive, the two-time NBCC Finalist’s latest novel, explores the same subject in a layered narrative about family, immigration, justice, and hope. Profound and poetic, this ambitious novel is a modern classic in the making, one that should be considered required reading for any American — really, any person — who hopes to somewhat understand the unknowable experiences of the lost children of the world.

Lost Children Archive is a rich tapestry of heartbreaking stories: Stories of families separated by space and circumstance, of children lost, missing, or presumed dead, of people searching for salvation and finding in its place more tragedy. Threading them all together is the story of a family — a wife and mother, her five-year-old daughter, a husband and father, and his 10-year-old son — on the road, driving from New York City to the Arizona-Mexico border. The decision to relocate to Apacheria is prompted by the unnamed couple’s work as audio documentarians. The father hopes to capture the last remaining sounds of the Apache culture. The mother, one of the book’s main narrators, is recording interviews, conversations, and the sounds of people and places connected to the immigration crisis. She is also on a mission to find out what happened to her friend’s two young daughters, who have been detained and whose fates are unknown.

As the family drives across the country, through places familiar and increasingly less so, they listen to music — the boy loves David Bowie’s “Space Oddity” — an audiobook of Lord of the Flies, and news reports about the happenings at the border they inch closer to every day. Eventually, they witness firsthand what they've heard reporters talking about on the radio. And then, they find themselves in a crisis of their own. As their journey continues, it becomes clear to the reader that something else is driving this family to the Arizona-Mexico border — something of much greater importance than their sound projects, their careers, and even themselves.

"Fear — in daytime, under the sun — is something concrete, and it belongs to the adults: speeding on the highway, white policemen, possible accidents, teenagers with guns, cancer, heart attacks, religious fanatics, insects large and medium," the unnamed mother and narrator says. "At night, fear belongs to children. It’s more difficult to understand its source, harder to give it a name. Night fear, in children, is a small shift of quality and mode in things, like when a cloud suddenly passes in front of the sun, and the colors dim to a lesser version of themselves."

She continues: "But it is not that, even. It is much larger than that. It is behind all that. Too far out of their grasp to be faced, let alone dominated. Our children’s fear is a kind of entropy, forever destabilizing the very fragile equilibrium of the adult world."

To say Lost Children Archive is timely feels insincere, considering how long humanitarian crises in Central and Southern America have been forcing migrants to seek out safety and stability in the north. But recent stories about the dangerous and often deadly journey families take in order to escape the brutality of their homes, about children being separated from their parents once they arrive at the border, and about the death of a toddler in a detention center on American soil does make Luiselli's new novel feel that much more urgent. Of course, it has never felt anything but urgent to those experiencing it, and those like Luiselli who have witnessed it firsthand. Nonetheless, Lost Children Archive does offer a crucial glimpse at the lives of the thousands of migrant children who continue to arrive at the U.S./Mexico border every month without their parents. Furthermore, it illuminates the lives, and the deaths, of the thousands who never arrive.

Through its shifting narrative viewpoints, Lost Children Archive asks important questions about the nature and importance of storytelling, fictional and factual. What does it mean to witness tragedy, to see true horror? What responsibility do we have to record it, to preserve it, and to present it to others? Who has the right to talk about it in the first place, and where is the line between sharing essential stories and exploiting those you’re telling stories about?

"I hear words, spoken in the mouths of children, threaded in complex narratives. They are delivered with hesitance, sometimes distrust, always with fear,” Luiselli writes in Tell Me How It Ends. “I have to transform them into written words, succinct sentences, and barren terms. The children’s stories are always shuffled, stuttered, always shatter beyond repair or narrative order. The problem with trying to tell their story is that it has no beginning, no middle, and no end."

Similarly, there is no simplicity in the narrative structure of Lost Children Archive, and like in real life at the border, there is no easy ending. The story is still being written, being told, and perhaps most importantly, being heard.