Books

This Memoir By A Sci-Fi Icon Is A Must-Read For Creators Who Are Scared To Take A Break

I wish I could say that I discovered Samuel R. Delany as a book-hungry teen, like I did with so many of the other sci-fi legends. I wish I could say that I've been reading his books for years, or that I've always given him due credit as one of the fathers of modern speculative fiction, or that I've been lobbying for an HBO adaptation of Dhalgren. But the truth is, I'd barely heard of Samuel R. Delany before I picked up a battered, third-hand copy of his memoir, The Motion of Light in Water: Sex and Science Fiction Writing in the East Village.

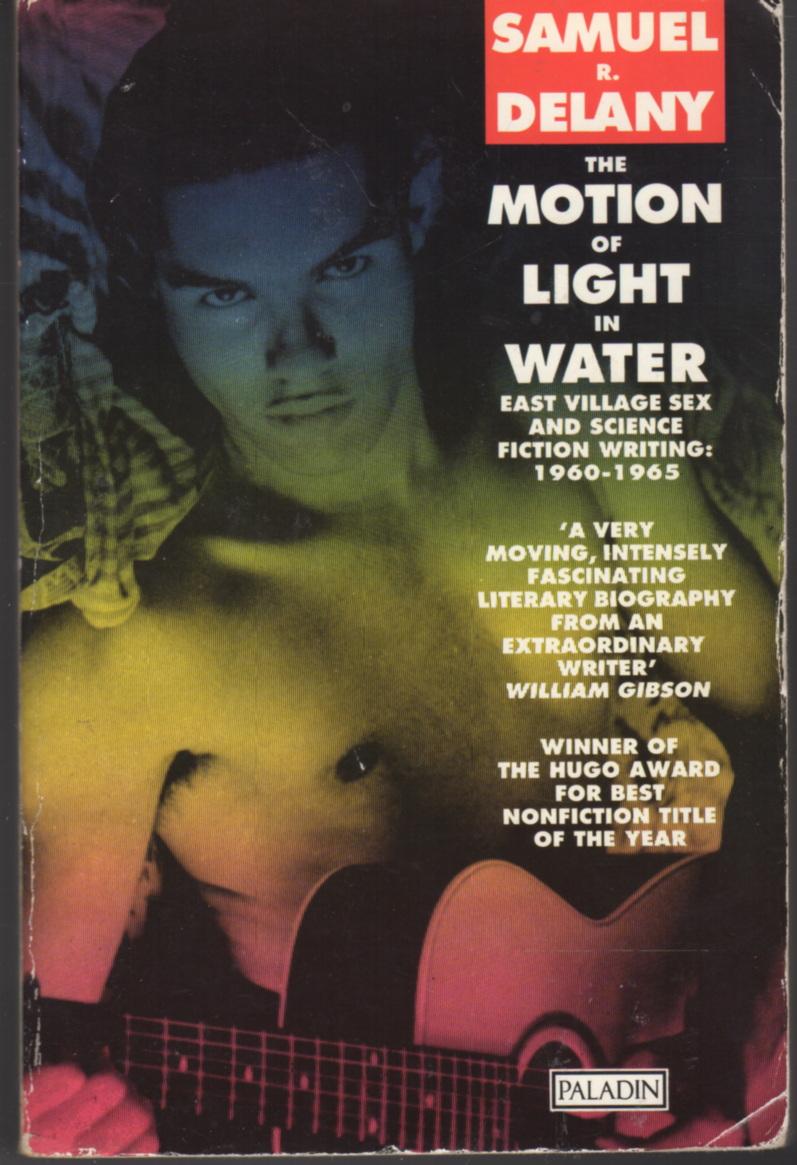

I think it was the subtitle that hooked me. That, and the cover: a grainy photo of a young, shirtless Delany, holding a guitar, with a rainbow gradient filter layered on top. To a modern reader, it looks more like a Tinder photo than a book cover, but it sets the stage well. This is a book about Delany coming to terms with himself as a young, black, gay science fiction author in the late '50s and early '60s, when that intersection of identities was all too rare. It's a time capsule, a portrait of the American '50s as they actually were—not just milkshakes and poodle skirts, but police raids and experimental theatre and crossing state lines to obtain an interracial marriage certificate.

And it's a must read for every young artist out there.

The Motion of Light in Water by Samuel R. Delany, $19.26, Amazon

Delany, you see, started writing straight out of high school. By the age of 22, he had published four novels (and written five). Each birthday spurred him on to write more and write faster.

"Birthdays have always pushed me to work harder. My twenty-frst was on me...I'd progressed several hundred pages in 'Voyage, Orestes!' and had told Cade and Bobs I had perhaps another six months of work to do till completion. Suddenly, however, I put it aside—and by sheer will forced myself through the handwritten draft of the concluding three chapters of 'The Towers of Toron.'"

Whenever he finished a project, he plunged directly into the next one. Slowing down or stopping was a terrifying prospect.

"Following my superstition, immediately (within minutes? hours?) I started writing the opening chapter of 'City of a Thousand Suns.'"

Delany had also got married straight out of high school, to the poet Marilyn Hacker. Their marriage was open and complicated (both authors now identify as gay), and when Delany wasn't writing, he was cruising around Manhattan for sex. Or exploring the burgeoning art scene of the '60s. Or bumping into the likes of Bob Dylan, Stokely Carmichael, W. H. Auden, and James Baldwin, some of the innocuous walk-on characters who appear in his memoir alongside a memorable cast of artists and lovers.

This account of life, love, and New York's ever-evolving subcultures is more than enough for a fascinating piece of literature. But The Motion of Light in Water goes beyond a simple recording of Delany's first few years of adulthood. It's a contemplation of how art intertwines with identity, as much as it is a window into another era.

The more the young Delany writes, after all, the more he feels an aching anxiety rising in his chest. He wakes in a panic and experiences dizzying, irrational, crippling fears, triggered by everything from heights to subway cars. He compares it with the same feeling he experienced years later, after losing the only copy of his manuscript for the novel Voyage, Orestes!

"Take that ache, now, and move it, very carefully—don't jostle it, because the slightest jar will make the buttocks, belly, and jaws clamp and the eyes blur with water, breaking the world into flakes of light—just to the start of what comes next. Not the motivation for the feeling, certainly. (The manuscript was not lost till five years later.) But rather the feeling itself: the absence, the obliteration, the frustration, the absolute oblivion—for such a feeling was at the center of what I'm going to write about now."

Finally, Delany lands in the hospital, where he begins to come to terms with the extreme pressure he's been putting on himself—pressure to write more and write faster, in a genre that most people regard as "pulp" and "trashy." Pressure from society, to hide his sexuality, to exist at a tense intersection of multiple identities.

"I was a young black man, light-skinned enough so that four out of five people who met me, of whatever race, assumed I was white...I was a homosexual who now knew he could function heterosexually. And I was a young writer whose early attempts had already gotten him a handful of prizes...So, I thought, you are neither black nor white. You are neither male nor female. And you are that most ambiguous of citizens, the writer. There was something at once very satisfying and very sad, placing myself at this pivotal suspension. It seemed, in the park at dawn, a kind of revelation—a kind of center, formed of a play of ambiguities, from which I might move in any direction."

Living in this "pivotal suspension," though, has exhausted him. Delany doesn't ever suggest that he was wrong to write with such determined enthusiasm, or to love science fiction, or to experiment with who he was and how he fit into society—but he is brutally honest in showing just how those pressures can grind down a young artist. And how important it is to take a break. To care for your own psyche. Young Delany only begins to feel free once more when he finally gives himself permission to rest, and to talk openly about his experiences.

"Was I scared? Yes!

But I was also scared not to. My breakdown had frightened me...Therefore, talk, I decided, was what I'd better do."

Whenever I feel that sinking sensation, that sense that I am desperately behind everyone else and about to be consumed by internal and external pressures, I reach for The Motion of Light in Water. Delany captures the joy and the beauty of creation, whether you're a sci-fi writer, a poet, a shirtless guitar-player, or something in between.

But he also captures the importance of balance for young artists—of creating time and space to rest, to recover. And to explore living within your own personal "play of ambiguities," like light moving across the surface of the water.