Books

This Book Will Help You Make Sense Of One Of The Most Controversial Feminist Writers Ever

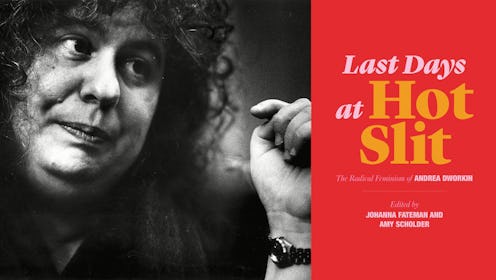

Andrea Dworkin is still misunderstood. To quote Gloria Steinem, "Hardly anybody is as misunderstood as Andrea." But now, a new anthology of her work aims to put the incendiary ideas that Dworkin became known for — her antipornography activism, her own history of sex work, the untrue claim that she said "all sex is rape" — within the context of her entire body of written work. Last Days at Hot Slit: The Radical Feminism of Andrea Dworkin, edited by Johanna Fateman and Amy Scholder, and out from Semiotext(e) in March, is a collection of excerpts from Dworkin’s letters, speeches, nonfiction, and novels. And it’s a book that a new generation of feminists should want to get their hands on.

Titled after the original working title of the manuscript that would ultimately become Dworkin’s first book, Woman Hating, Last Days at Hot Slit presents readers with chronological, bite-sized bits of Dworkin — winnowing down her inflammatory ideas, difficult content, and relentlessly explicit language into easily digestible snapshots that paint a comprehensive portrait of everything Dworkin was.

Moving beyond the nonfiction that Dworkin is most known for, Last Days at Hot Slit shows the Dworkin who wrote to her parents — seeking understanding, approval, and sometimes money. It recognizes Dworkin as a fiction writer in a way that hasn’t been done before. It charts the evolution of a feminist writer and thinker who was so much more than the sometimes-accurate ideas attributed to her. It celebrates, as Fateman writes in the introduction to Last Days at Hot Slit, the “apocalyptic, middle-finger appeal of her prose.” If you misunderstand Dworkin after reading this anthology, you’re not trying.

Because that’s the thing about Andrea Dworkin — not only is she the most misunderstood feminist writer, activist, and icon, she’s also the most willfully misunderstood. She was one of the first feminist writers to write openly about her own experiences of rape, domestic violence, and sex work; she was an early intersectionalist; she was a feminist unafraid to toe the line of misandry — though, in my opinion, she never crossed it. There is no easier way to dismiss Dworkin and her radical ideas than to make sure that the misunderstanding of her ideas overshadows the legacy of her ideas themselves. (Is Dworkin ever invoked without the necessary caveat that she never actually said “all sex is rape”?)

Most certainly, her anti-porn, anti-prostitution stances, as well as her surprising alignment with the political Right — in those two, specific instances — pit her against the third wave feminists who were focused on sexual liberation and the ever-raging war on accessible contraception and legal abortion. Yes, much of her writing on sex was predicated on the belief that within the construct of a patriarchal society, heterosexual sex required some amount of subjugation, and often a woman’s complicity in her own. But when you examine Dworkin’s criticism as she wrote it — of a patriarchy more powerful than the individual men who populate it — her core ideas are hard to argue with. Perhaps in an era when a man is less a prerequisite for a woman’s sexual satisfaction than ever before, Dworkin’s writing is more threatening to the patriarchy than ever.

The overarching theme of critiques of Dworkin (that she was a “man-hater”), whether they come from men, women, or even fellow feminists — and very often, especially in her lifetime, they came from fellow feminists — are themselves rooted in patriarchal constructs. Perhaps nothing indicates the insidious dominance of the patriarchy more than the idea that, while misogyny is a core implication of the patriarchy, misandry is simply a step to far for feminism.

Yet, Dworkin was not a man-hater, no matter how history would like to minimize her. She was a woman whose rage was, likely, too much for her generation to handle. It’s a rage I like to think my own generation of feminists is ready, willing, and able to take on (and we are, aren’t we?). And finally, Last Days at Hot Slit presents Dworkin as the furious, depressed, inquisitive, dare I say optimist, who she was. “Just as it was her curse to see the seed of genocide in everything — the calamity waiting in every expression and symbol of inequality, however small or private —" writes Fateman, in the anthology, “it was her gift to see in everything the opportunity to resist.”