Books

This YA Novel Explores The Grief After The Death Of A Parent – & You Can Start Reading Now

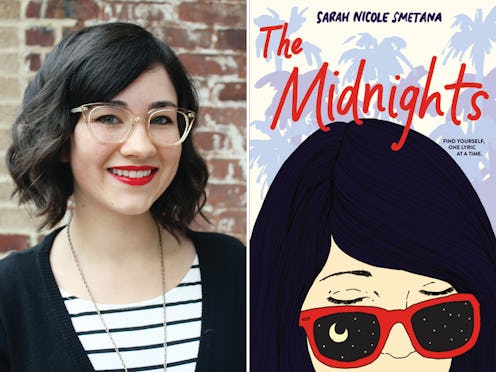

You know when you get a song stuck in your head and you find yourself humming it all through the day? That's like The Midnights by Sarah Nicole Smetana. Its musical prose and moving characters will stick in your mind even after you've stopped reading. And though it's not hitting shelves until March 6, we have an exclusive excerpt to introduce you to her gorgeous story right now.

Smetana's debut young adult novel follows teenager Susannah Hayes, who's trying to drag her aging rockstar father out of his past long enough to pay attention to her and her own musical talent. But when Susannah's father dies, her entire life is uprooted. Her mother moves her to a new state, where Susannah realizes she can reinvent herself as a rockstar in her own right and become the confident face of a band. However, it slowly becomes clear that she's not the only one in her family keeping secrets, and the revelations will shake her life once again.

Smetana draws from her own experience writing music and playing in bands to tell her story of Susannah struggling to find her voice. As an Orange, California native, Smetana also brings the Southern California setting alive in a dreamy burst of color.

Check out below the (stunning!) cover for The Midnights for an excerpt of the upcoming novel!

Excerpt

I set the urn down on the kitchen table next to my mother’s visual to-do list — a towering mound of receipts, mail, and miscellaneous clutter. She’d been inspecting a letter when she heard the thud, and she jerked up at the sound.

“Jesus, Susannah,” she said, one hand over her chest. Then her eyes floated down to the urn. “What is that?”

The white ceramic vase looked fake, like a prop in a movie, with little peach flowers frolicking around the rim. If it weren’t so heavy, I might have thought the whole thing was a hoax — that he wasn’t in there, wasn’t even dead.

But there was no mistake; the mortician had his wallet, along with a few of his other belongings. I put them on the table. Most of them, anyway.

"If it weren’t so heavy, I might have thought the whole thing was a hoax — that he wasn’t in there, wasn’t even dead."

“I guess we should’ve answered the phone,” I said.

“You didn’t...." She pointed in the urn’s general direction and swirled her finger through the air, unwilling, I suppose, to say anything more specific about the ugly thing. “I mean, this wasn’t your choice, was it?”

“Please,” I said, and sat down next to her. “The guy told me they chose their most popular style when they couldn’t reach us. I guess their entire customer base is made up of old ladies survived only by their cats and doily collections.”

The left corner of my mother’s mouth curled up before drifting back down again. “There’s something so eerie about it. Just knowing he’s in there, beneath those hideous flowers.” She sighed. “Where do you even put something like this?”

“On mantels, I guess.”

“There’s something so eerie about it. Just knowing he’s in there, beneath those hideous flowers.” She sighed. “Where do you even put something like this?”

“If he saw this . . .” My mother slipped into laughter. She covered her mouth, trying to hold in the sound, and I remember thinking she looked a little bit unhinged right then, yet at the same time, a little bit free.

The next thing I knew, I was cracking up too.

“He would hate it,” I said. Hot tears spilled down my cheeks. “It would seem more personal if we kept him in a coffee canister.”

My mother smacked her hand on the table and a few unopened envelopes slipped to the floor. “Maybe we should transfer him. Can you imagine what he would do if he saw those flowers?”

I shook my head, jaw aching. But the truth was that I could imagine.

“You think this is funny?” he would say, feet planted wide, trying to look menacing. “Yeah, go ahead. Laugh it up. It’s goddamn hilarious, as long as it’s not happening to you. How would you like spending eternity inside this hunk of shit, huh?” And for a second I thought I could actually see him, right over my mother’s left shoulder, fighting the smile that tried to break free of his taut lips.

A shrine did not suit my father any better than a burial, so in the end, we took his ashes up to the ridge. It was my mother’s idea.

“Is this legal?” I asked, cradling the urn like an infant.

“Probably not,” she said. “But it’s all ash up here now, anyway.”

Blackened grass crunched beneath our feet as we climbed, past the signs warning of coyotes, of fire hazards, of the newly restricted area. At the top, I took the urn to my father’s boulder. The summer heat had finally broken and a brisk evening breeze swooped down at us from the marbled sky. Sometime that week, all the remaining smoke clouds had been blown out to sea, and the city was back to normal. I closed my eyes and imagined my father sitting there at the edge, chucking pebbles out into the canyon. When I opened them, there was only the city, the sunset, a two-dimensional image reproduced on a million postcards lining the shop fronts of Hollywood Boulevard. A sprawling city that my father had fought for, that I hardly even knew at all. Right then, Los Angeles just seemed like another piece of him I could not claim.

I walked out to the ledge, lined up the tips of my shoes with the lip of the rock. My body wavered, unbalanced.

"I closed my eyes and imagined my father sitting there at the edge, chucking pebbles out into the canyon. When I opened them, there was only the city, the sunset, a two-dimensional image reproduced on a million postcards lining the shop fronts of Hollywood Boulevard."

“Be careful,” my mother said. “Maybe you should move back a little.”

“I’m fine,” I said, and opened the urn.

I let my fingers glide through my father’s remains before extracting a handful and flinging him into the air. For a second he hung suspended, a beautiful haze of gray dust. Then the wind rose up from beneath and the cloud dispersed. Some particles took flight, out toward the freeway, while others dove down into the valley or gathered around my feet, immediately blending into the charred landscape. I threw a second handful. A third. A fourth. And I thought about how easy it was to vanish.

“He’s part of the city now,” my mother said. “He always wanted this.”

I nodded, but now that it was over, I couldn’t help thinking she was wrong. We both were. I felt a frantic urge to scoop some part of my father back into the jar, to take him elsewhere, do everything over. Maybe he would have wanted to become the ocean instead, one portion lapping at the California shore while other specks floated out to Hawaii, to China, slipping through tributaries into the Amazon or the Black Sea. Looking down at my feet, I couldn’t distinguish between my father’s ashes and the ashes of burned trees. As the silence around us deepened, I realized we hadn’t even given him a soundtrack.