News

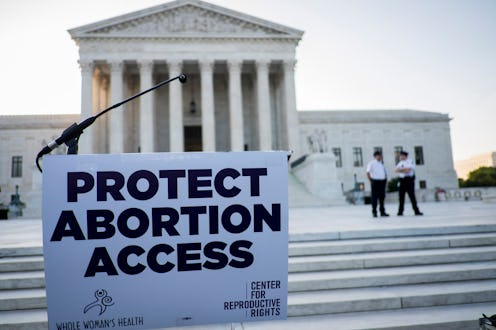

A Physician & A Lawyer Explain Why The Recent Wave Of "Heartbeat" Bills Is So Troubling

Over the past several weeks, legislatures in Georgia, Kentucky, Ohio, and Mississippi have passed or advanced so-called "heartbeat bills." These anti-abortion laws would make it illegal to obtain an abortion after the detection of a "fetal heartbeat," which doctors say is an inaccurate indicator for determining when life begins. While the proponents of this legislation cast it as a push to “protect the unborn,” experts tell Bustle that these regulations can have serious legal and medical consequences.

First off, it's important to note that doctors don't agree among themselves on whether cardiac activity detected in the first two months of pregnancy should even be referred to as a "fetal heartbeat." Instead, some physicians say the proper term to use is "cardiac pole activity," because the rudimentary structure producing the sound bears little resemblance to an actual heart.

Reproductive rights lawyers and physicians point out that banning abortions based solely on this cardiac activity erases the challenges that some pregnant women face. Bills that prohibit abortion after a so-called "heartbeat" is detected don't consider the fact that all menstrual cycles and pregnancies aren't uniform, according to Dr. Catherine Romanos, a fellow with Physicians for Reproductive Health who practices family medicine in Ohio.

The "heartbeat" detection litmus test "is completely arbitrary, and could vary a lot" from patient to patient, Romanos tells Bustle.

Romanos says cardiac activity is an inaccurate measure of when life begins in part because it can be detected as early as five weeks into gestation, and sometimes it isn't detected until much later. On top of that, she explains, while people typically get their periods in the fourth week of their menstrual cycle, that's not the case for everyone. Some even bleed regularly all throughout pregnancy, which can be mistaken for menstruation. Romano says even the most regular menstrual cycle can leave very little time for a woman to decide whether she wants to have an abortion, if she lives where a so-called "heartbeat" ban is in place.

“You maybe have two or three days to decide what you’re going to do,” Romanos estimates, which for many people is hardly any time at all to make a massive life decision — let alone come up with the money to afford an abortion and to take time off of work for it.

There may also be complications during pregnancy that these bans don't take into account. It's possible for a woman to develop an infection that makes her pregnancy dangerous or nonviable, even as she maintains a detectable "fetal heartbeat," according to Romanos. She says that scenario may create a medical and legal gray area in places where abortion is banned upon the detection of cardiac activity.

Someone may seek an abortion out of concern for their own mental health. Romanos says she twice recently had patients tell her that they needed an abortion, or else they might harm themselves. Such a situation isn't explicitly accounted for in this recent wave of restrictive bills, some of which may provide exceptions if a woman's physical health is at risk, as is the case in Mississippi.

Lucinda Finley, a professor at the State University of New York Buffalo Law School who has litigated cases involving abortion clinics, including one that went before the Supreme Court, agrees that legislation this restrictive can produce legal gray areas. She points to women who access abortion medication online, without the help of a doctor, as an example. If a woman hasn't had an ultrasound or consulted with a doctor, she would have no way of knowing whether cardiac activity was detectable.

"Would a prosecutor in one of these states go after her?" Finley asks, rhetorically. "It would really depend on how a law is written. Are these laws written to exclude the prosecution of women?"

Ultra-restrictive abortion bans could potentially open up women for prosecution if a miscarriage is misconstrued as an attempt to illegally terminate a pregnancy, Finley says. This has happened in some countries in Latin America. El Salvador, where abortion is illegal in all circumstances, came under scrutiny in 2015 when reports indicated that 17 women had been jailed after they experienced miscarriages or other pregnancy-related complications, according to The Telegraph.

"Politically, I doubt that any district attorney in any of these states would go that far," Finley tells Bustle. "But it's possible."

From a legal standpoint, Finley believes the recent wave of "heartbeat" abortion bans is intentional. She notes that the Supreme Court identifies two cases in which state governments may regulate abortion: protecting women's health and protecting "potential life." According to Finley, courts have repeatedly ruled that protecting women's health is the dominant priority, and the Supreme Court has required legislators who pass abortion regulations to provide evidence that they would in fact protect women's health. Because of this, she says anti-abortion politicians have pivoted toward legislating on the basis of "potential life."

She points to the most recent Supreme Court abortion ruling, Whole Woman's Health v. Hellerstedt, as an example. In that decision, the court ruled that Texas legislators could not make it difficult for women to obtain abortion care by imposing medically unnecessary restrictions. Specifically, the court struck down legal provisions that required doctors to have admitting privileges at a nearby hospital and required abortion clinics to meet the same standards as ambulatory surgical centers, according to the Harvard Law Review.

"The Supreme Court said, basically, 'Look, if you're going to claim that a restriction on abortion is being passed to protect women's health, you better have real medical evidence that [the restriction is] actually necessary to protect women's health, and actually does protect women's health,'" Finley explains. She says it's because meeting that test has become so difficult, the "potential life" of a fetus is now the focus of many abortion bans.

Romano says these "heartbeat" bans are not concerned with protecting individual pregnancies. Rather, she says their aim is to "prevent women from getting abortions at all."