28

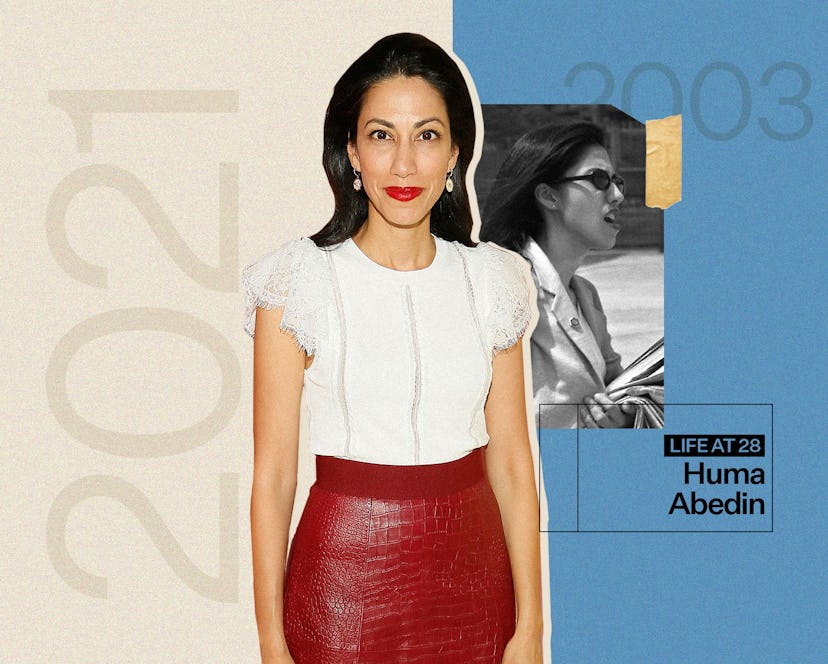

At 28, Huma Abedin Was Sleeping On Couches & Wearing Zara

With her new memoir, ‘Both/And,’ Abedin finally tells her own story.

In Bustle’s Q&A series 28, successful women describe exactly what their lives looked like when they were 28 — what they wore, where they worked, what stressed them out, and what, if anything, they would do differently.

Contrary to recent press, Huma Abedin can be late — slightly. “I've been running late all day, just so you know,” she apologizes. Abedin has spent the last two weeks promoting her new memoir, Both/And, one of the most anticipated books of the year. She is as chic on a video call as in all of the Vogue coverage she’s received over the years — she wrote a lot of the book at the home of her good friend, Anna Wintour, who also hosted her book party — but Abedin is also chewing. She’s only just made time to squeeze in a quick lunch, which seems to have emerged at least in part from a Ziploc bag. You don’t get where Abedin has gotten — and survive what she has survived — by forgetting to bring a snack.

Abedin is obviously proud of this book, which has given her the opportunity to honor her parents, professors who raised her first in Kalamazoo, Michigan, where they were working when she was born, then in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, where she lived from age 2 until she moved back to the United States for college at age 17. It allows her to chronicle the more than 20 years she has worked as Hillary Clinton’s “ubiquitous” right hand and to finally give her own account of her marriage to former Congressman Anthony Weiner, a storybook Washington romance destroyed by highly publicized online betrayal. Between 2011 and 2016, Weiner repeatedly sent sexually suggestive images to other women via social media and texting apps, including one taken with Abedin and Weiner’s son, Jordan, then 4 years old, sleeping beside him. In 2016, following reports that one of those women was a 15-year-old girl, federal authorities seized his electronic devices, including his laptop, which happened to contain some of Abedin’s work emails. The discovery of the emails prompted the FBI to reopen its lengthy investigation into Clinton’s emails 11 days before the election, an event often thought to have cost Clinton the presidency. Weiner served 18 months in federal prison.

What is surprising about the memoir, which just made the New York Times bestseller list, is the degree to which 46-year-old Abedin — accomplished, poised, so glamorous she is sometimes mistaken in the grocery store for Amal Clooney — still portrays herself as the perfect helpmate, in work and life. She began this interview listing other illustrious women we should spotlight for 28, then said, “I should be a producer for you.” Abdein comes across as impossibly innocent for someone who has seen so much: ever industrious; unquestioningly loyal to Clinton, who herself dealt with the most public marital infidelity in history and whom Abedin describes in almost hagiographic terms; and faithful to her values as a practicing Muslim. Here is a woman who survived her 20s in Washington without alcohol.

Abedin turned 28 in 2003. (“The only thing in the world about me that is inaccurate is my Wikipedia page,” she says. It and many other sources list her as born in 1976. Abedin says that one news outlet writing about the book informed her “only you are telling us 1975.” She sent a picture of her passport as proof.) Back then, she had already met Weiner, who was serving in Congress, but they were not yet dating. Instead, she wore clothes off the rack from Zara, crashed on friends’ sofas, and always stayed two steps behind Clinton — which may or may not be where we find her today.

What did life look like for Huma Abedin in 2003?

I had this peripatetic life between New York and D.C. because Hillary was now in the Senate. I kind of lived like a college student. I mostly slept on my good friend Allison Stein’s couch whenever I was in New York. Sometimes we’d get a hotel. I stayed at the Holiday Inn in Mount Kisco a lot because that was near Hillary’s house.

I still had my one-bedroom, 800-square-foot apartment that I lived in with a roommate in Washington, D.C. This was an apartment my mother bought on 24th Street. It had olive green carpet that I installed. Please don’t ask me what I was thinking. It was like from 1970-something. Maybe it reminded me of my childhood in Saudi Arabia. My roommate and I redid the kitchen in 2005, and I remember when they stripped all the walls and the floors, there was mold and asbestos. We had to live somewhere else for a week.

One thing people already knew about you, or at least about Hillary Clinton, is that you work all the time. Was that true in 2003?

If Hillary Clinton got up and went anywhere — anywhere — I went with her. Now when I say it, it seems kind of crazy, but back then, yeah, I was doing everything.

You mean “self-care” was not top of mind?

I was so unhealthy. I didn’t exercise except for running around after my boss. I would not eat breakfast and for lunch, I would have a power bar and a cup of coffee, and by the time I would get to dinner at 9 or 10 o’clock, I was starving.

In my 20s, I really kind of took my friends for granted, whether it was my college friends, my roommate, friends from work. I was always busy. I would call and say, “Oh, we just landed from Buffalo. I’m starving. Order me these five things.” I would just show up and eat. Food is always something that is really animated in me. I don’t drink. I don’t smoke. But I can eat two pastas and two ice cream sundaes for dessert and be perfectly happy.

You’re known now in part for your elegant and distinct personal style. Did you always have it?

I was the loud, clumsy one in my family. My older brother and sister were smart. My little sister was the beauty. I was falling all over myself. But I loved clothes.

[When] I was a little girl, we’d go to the States, and I would get Glamour, Seventeen, and Vogue, and I would tear out pictures of dresses and be like, “Mom” — I would call her “Oma” — “Oma, I want this.” My mother would say, ”Oh, that looks like silk.” We’d go to the tailor. That was one of the nice things about living in Jeddah. You’d go to the fabric store and there were bolts and bolts of fabric. So I had this kind of grounding. I had a little bit of understanding of how clothes were made.

What were you wearing at 28?

I was on a government salary. I did a lot of J.Crew or Zara. I saved up and invested in one black Prada pant suit, and I wore it to shreds. I know what looks good on me, and I feel like I had that sense ever since I was younger, and I kind of stuck to that.

You write that you weren’t thinking about marriage at all in your late 20s, but you also say that you assumed you would marry a Muslim man and “there was no one to marry.” When you did think ahead, was partnership something that was important to you and if so, did you have any anxiety about not finding it?

No, I had such certainty that I was going to find the right man. I think like many women do, I used my parents as the model for whatever marriage was supposed to be, [and] for me it was perfect. I thought a man like my dad was going to walk up to me and say something really charming and sweep me off my feet, and we would be equal partners in life and love and work, intellectually and all those things.

After I started the book, I found a letter I wrote to my mother in 1998-99 about attending somebody’s wedding. In the letter, I said, “I’m sure she’s going to have a very happy life. All I know is I don’t want to be married for a very, very, very, very, very, very long time.”

I thought, “It’s going to come, but there’s plenty of time.” I don’t know where that comes from. I got married at 35. I was pregnant at 36. People said, “Oh, you’re an old mother.” I didn’t feel that way. I think in hindsight that probably served me well.

One of the most striking aspects of your story is that you were full of ambition, but in other ways you come across as more traditional or conservative. I’m thinking specifically of the choice not to have sex before marriage. Was that decision related to your faith or upbringing?

My mother is a sociologist. Even back then, she was writing articles about the withdrawal method for birth control in Muslim communities. Most conservatives are like, “Oh my God, you can’t talk about this.” In our house, you could talk about it.

You could have any conversation in our house. When I got my period at 11, I ran and told my dad.

I just felt like my life was going to be different. I was different. I think if I went off to America and wanted to sleep around with a bunch of boys, I could have. I just chose not to. Believe me, I know friends who left [Saudi Arabia] and went to the United States or U.K. and just had all the parties.

It’s not how I was wired. It’s not how I am wired, I guess.

You thought about going to law school after the Clintons left the White House. Why did you stay on?

It always felt like I was growing in the job. I was the personal aide in the White House. In 2001 after they left, I became more of a senior adviser and less an assistant. There was a new responsibility, a new project. I wanted to do it well. I’m not a policy person. I was never a policy person. I wanted to understand what she was doing, what she was writing about or talking about.

A colleague who read the book said there’s a great love story here, and it has nothing to do with Anthony Weiner. It’s about you and Hillary.

That’s very funny. Look, there are women who have known her longer than me and probably feel closer to her than me. The difference was I was with her.

For women who supported Clinton in the 2016 presidential campaign, her loss meant so many things, but the way you’ve documented her work brought to mind another consequence of the 2016 election: There won’t be a Hillary Clinton presidential library where all of this is recorded.

One of the many reasons I wrote the book [was to] show what it’s like to work with and for Hillary Clinton — being on a campaign with her, being on these missions with her. This is my record.

I want there to be a Hillary Clinton library. Don’t think we’re not working on stuff.

In the book, you make it clear that, despite all the sacrifices it has required, you would do your career all over again. Would you say the same about your marriage?

I did live in the “what if” world with Anthony for a period. However — not to be cliche about it — he gave me the single most important thing in my life. Without Anthony, I don’t have Jordan, and I can’t imagine a life without Jordan.

What about in the aftermath? Would you second-guess the decisions you made there?

I tried to do the best thing for my son. It was a long, long journey. I had to get myself into proper therapy.

Maybe I would have tried to understand the challenges of mental health better. I did not understand. I spent a lot of time in shock: I don’t get it, I don’t get it, I don’t get it. I didn’t know anybody divorced growing up. You didn’t go to a therapist; you didn’t talk to strangers about your problems.

There’s this stunning moment you write about when you were engaged and Weiner said to you, “I’m broken, and you need to fix me.” Did that register on some level as a red flag?

My guess is if you ask Anthony, he’ll say he didn’t remember even saying that. It’s only in hindsight that it seems significant to me. Back then, I thought it was a joke. It was meant as a joke, and I took it as a joke.

I thought I was marrying the perfect man. He was perfect in so many ways. And in other ways completely destructive. Self-destructive more than anything else and taking the rest of us along with him.

I [also] think the idea of online betrayal was new. I would argue that we were one of the first. I mean, people had scandals in politics before 2011, but entirely virtual, online? It didn’t exist. These portals didn’t exist.

Everyone asks you this, but what’s next?

I suppose I can add author to my resume.

That’s helpful because your Wikipedia page also still lists your occupation as “political staffer,” which is understating it just a little.

I appreciate that.

This book has been a kind of liberation, an open[ing]. The point you just made about [me] kind of being conservative and closed about many things — I’m open to whatever, and I hope that some interesting opportunities that make themselves obvious to me. I don’t know what they are. If you have any ideas, let me know.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.