Rule Breakers

Behind Her Viral Art, Morgan Harper Nichols Is Working On Self-Forgiveness

In February, a long-sought diagnosis finally gave the poet some answers.

In 2014, Morgan Harper Nichols was living any singer-songwriter’s dream. A few days a week, the Atlanta native would join her younger sister on stage in Nashville to perform contemporary Christian music, with an acoustic guitar in hand and a deep alto voice to round out her younger sibling’s soprano. But the shows often left her depleted, and while on stage, she’d take out her in-ear monitors. The noise was too overwhelming. Off stage, she and her husband were constantly broke, despite her publishing deal with Capitol Christian Music Group. She had intrusive, spiraling thoughts: Why do I feel so drained? Why do I feel so tired? Am I a failure?

So she quit. The couple moved to Dallas, where she did freelance design work; he, construction jobs. On a rainy November night in 2016, still underpaid, underemployed, and feeling desperate, Harper Nichols put her feelings on paper. Without a melody, the lyrics read as a poem.

“When you start to feel/ like things should have been better this year/ remember the mountains and valleys that got you here,” it starts. She added her name to the bottom and uploaded the message to Pinterest. By January 2017, it’d been favorited 100,000 times.

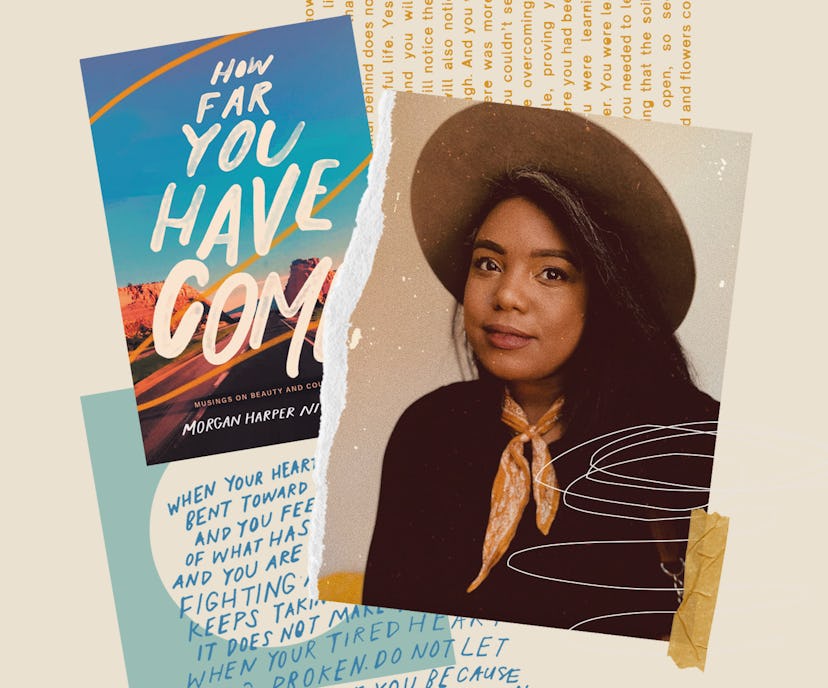

Now, four years later, Harper Nichols’ work is sold at Pottery Barn, Anthropologie, and on her e-commerce site. She hosts a regular podcast, just released her third poetry collection, How Far You Have Come: Musings on Beauty and Courage, and in February, was diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder, news she shared with her 1.7 million Instagram followers. She’s trying to extend the same easy grace to herself as she does to them.

“I was working overtime to keep up socially and would miss out on social cues, like the tone of someone’s voice, which would lead to a miscommunication or awkward moment,” says Harper Nichols, 31. “I would cycle through what could be wrong, like, Maybe I'm sleep-deprived or stressed. I got to a point where I was like, There's got to be something more going on here.”

An answer came from TikTok. Unwittingly, she stumbled on videos from users like Alexandra Pearson and Paige Layle, who share stories about having autism as adults. Their experiences were familiar enough that Harper Nichols contacted a specialist.

According to Francesca Happé, a British neuroscientist at King’s College London, it’s possible that hundreds of thousands of girls and women are living with undiagnosed autism. A 2020 study in the Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders found that girls are better at camouflaging their autistic traits than their male counterparts, which could explain the gender discrepancy, and also why women are more likely to be diagnosed as adults.

For Harper Nichols, her autism manifests as sensory overload and difficulties with executive functioning and social cues. “One of the main things my specialist told me after reading the diagnosis was, ‘It's not your fault,’” she says. “I just cried, because that's what I've been telling myself for a very long time. I sat in silence. It felt like a relief. This is so cheesy, but a song that came to my mind was the old Dashboard Confessional song ‘Vindicated.’”

I spoke with Harper Nichols last month, a few weeks before the release of How Far You Have Come. She calls from Phoenix, Arizona, where she moved last summer with her husband and their toddler son, Jacob. For the first time in their adult lives, they have a backyard. “Just to be able to have a space where I can go outside, take my shoes off, and stare up at the sky, that feels like home to me,” she says.

In the book’s poems and essays, Harper Nichols works to locate herself in place and time. Narratively, the chapters cross the American South state by state, from Georgia to California. She reflects on the “ancestral legacy” of the Mississippi River, the Grand Canyon’s celestial grandeur, and New Mexico’s Sandia Mountains. The poems speak to present selves, future relatives, and ancestors, like an enslaved woman running toward freedom.

As the daughter of pastors, Harper Nichols’ poems borrow the language of the pulpit, like “grace,” “surrender,” and “divine.”

“Growing up in the African American, Black church tradition is, in many ways, different from a lot of the more mainstream Christian traditions,” she says. “There are still some churches who don’t want to say Black Lives Matter or don't see that as an issue that needs to be talked about.”

Harper Nichols’ poetry generally sidesteps political landmines like former President Trump and social justice movements, relying instead on palatable devotional messages. Nature and color palettes have always been comforting to her, in a way that navigating social situations has not been.

An exception came on Jan. 6. After the Capitol insurrection, the poet turned to Instagram to lambast historical ignorance. As she watched Trump supporters storm the U.S. Capitol building, she recalled her own visit to D.C. a few years prior. She’d felt conscious of her body in the heavily monitored space and worried about tripping, lest she set off some policeman’s internal radar. And she thought of her dad who, at age 19, had been “slammed to the ground by police officers” on his way home from church, having been mistaken for someone else. “That’s where my body went, that’s what came up for me yesterday,” she says on her podcast.

How Far You Have Come hints at some of these ongoing struggles, and others specific to 2020. “I was writing this book [during] the racial unrest,” she says. “How many people have to die before we pay attention? I have also lost people to the virus, [and] when those phone calls come in, and you can't go to the funeral because they're across the country, it's a different kind of grief. It’s heavier. You have to sit with it. I was watching all of these unfold at the same time, feeling helpless and angry and frustrated. And I was also beginning the process of being diagnosed with autism. I was grieving all those years when I had been so hard on myself.”

She works through these emotions with colors, swirled and layered on an iPad. One of her favorite quotes comes from the late abstract artist Alma Thomas, the first Black woman to have pieces hung in the White House. “Through color, I have sought to concentrate on beauty and happiness, rather than on man’s inhumanity to man,” Thomas said in 1970. Reading the line today, it seems to embody Harper Nichols’ work, her words of encouragement and understanding, placed atop a bed of pinks, greens, and blues.

I ask if she considers her poems spiritual. “For me, they are,” Harper Nichols says. “As I'm writing my poems, sometimes they're prayers for the future.”

This article was originally published on