Fashion

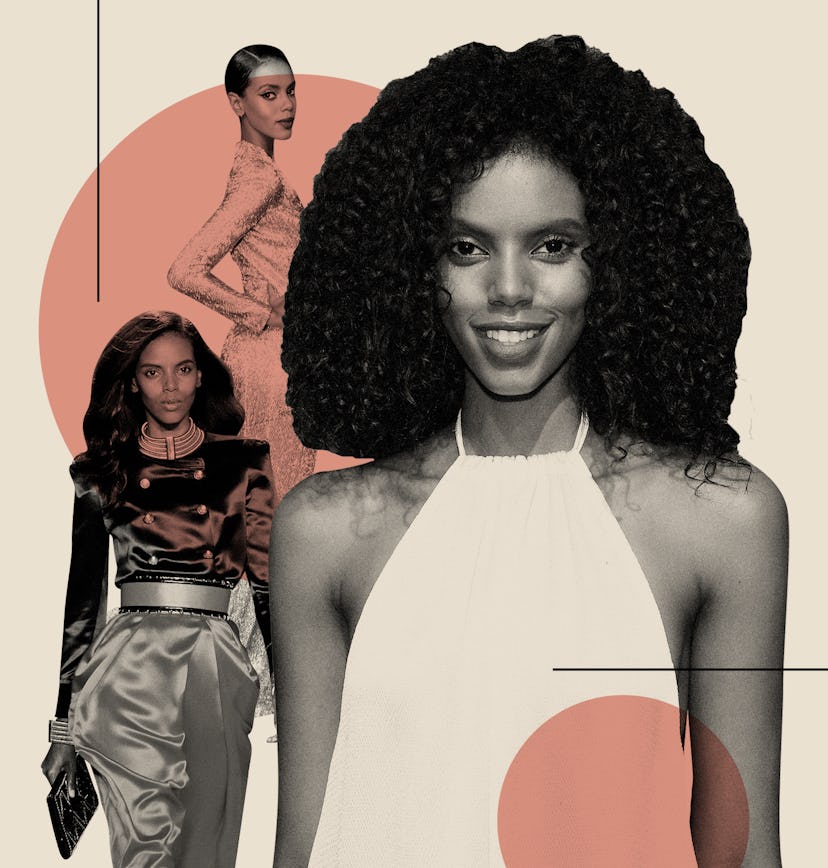

‘We’re Not Showcasing Black Girls’: Grace Mahary On Racism In Modeling

“The heaviness can be a lot to carry."

Grace Mahary is skeptical. “We’re in this for the long term,” the 31-year-old Canadian model says of the recent nationwide outrage that followed the death of George Floyd. “The real test will be in six months, if people are still dismantling their privilege. Will they still be buying from Black-owned businesses?”

Mahary has been a fashion industry fixture for 15 years, walking in shows for Givenchy, Saint Laurent, and Valentino, and she’s seen first hand how far the industry has to go to confront racism. “In fashion, the truth of the matter is the entire industry is racist,” she says over the phone from California. “Most experiences involve racism. Most positions have been corrupted by racism.”

Mahary’s own experiences are all too common. “I’ve read emails about how this designer in Paris — a very famous designer — said, ‘We’re not showcasing Black girls this season.’” she says. “What is that?” Tokenization has also been a source of division. “There is a reason why Black women in fashion felt like there could only be one. There are Black people who made their way to the top, but they were subject to fighting each other or thinking there can only be one Black person in this space, whether it’s a model, an editor, a photographer, or a stylist,” she says, citing a time when someone congratulated her for being the only Black model in a fashion show.

The real test will be in six months, if people are still dismantling their privilege. Will they still be buying from Black-owned businesses?

Mahary also once overheard people on a photo shoot condemning Black facial features. “This is what they’re saying on set — I'm here because I look like a 'White girl,' but painted Black, because I have 'European features,'” she says.

“The heaviness can be a lot to carry,” she says, noting that the solution requires real work, not performative allyship that sometimes takes the form of carefully crafted hashtags or black squares on Instagram. If all these fashion brands are now listening and learning, Mahary is listening harder.

“I don’t want to be anyone’s mascot,” she says, adding that she “didn’t want to speak on any platform that wasn’t owned or run by a person of color, specifically a Black person.” Mahary only granted Bustle this interview because she would be interviewed by a writer of color and because of steps the company has made to be more diverse, including hiring Black fashion director Tiffany Reid. “These are small steps, but they’re steps in the right direction,” she says. “The issue is that folks are reaching out to people of color for their thoughts on what’s happening right now without reflecting on what’s happening within their own companies.” The solution, according to Mahary, isn’t cancel culture, but accountability.

“I’m actually excited for this moment right now because many of us — from those just starting out to veterans — are going to hold these white people accountable,” Mahary says. “Brands with a very high percentage of [white people featured] in their advertising, making vanity statements [about Black Lives Matter] is a slap in the face. We’re exposing people for their truth.”

In fashion, the truth of the matter is the entire industry is racist.

She also believes fashion brands and publications need to make comprehensive efforts toward greater inclusivity. “Hire Black, buy Black, support Black. Really simple,” Mahary adds. “I love Aurora James and I love that she made up the 15 Percent Pledge.” The collective is calling on major retailers to commit a minimum of 15 percent of their shelf space to Black-owned businesses inspired by the current population of Black people in the United States: 15 percent. “Everyone should consider sticking to that and supporting minorities in a way that’s not like a quick Band-Aid.”

Mahary stresses that Black people also need to be promoted or hired in leadership roles, where they’ll gain the power to implement and enforce effective, long-term change. “I would love to see that, when you do hire Black, you promote them and they don't predominantly make up the administrative portion of the company. [...] There should be a much larger percentage of Black and Brown people in B-level and executive-level positions.”

Being an anti-racist advocate in fashion can be exhausting, so Mahary leans on her community for inspiration and strength. In addition to being a successful model, she is a certified sommelier and founder of the clean energy nonprofit Project Tsehigh. “Part of the reason I became a sommelier is because of my desire to diversify traditionally white spaces,” she says. “Project Tsehigh is based on the philosophy of supporting people of color: their companies, their initiatives, and their motives. This isn’t new for me.”

Mahary is also a restaurateur. “Chulita Restaurant is in Venice, California, and I visit and check in frequently,” she says. “I always talk to the staff, talk about what they’re up to and what inspires them. My way of working through the enormity of this moment is by diving into my passions and my community.”

This article was originally published on