28

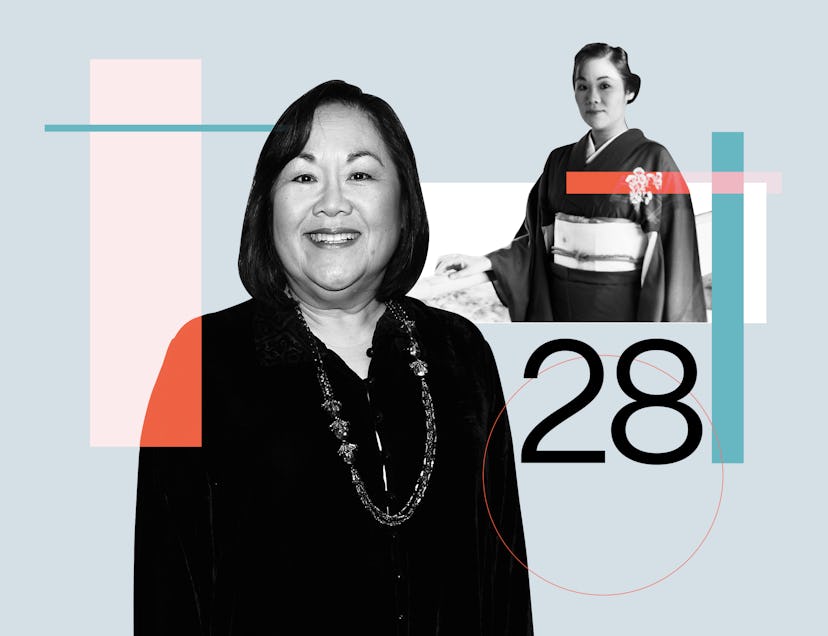

At 28, Gilmore Girls Star Emily Kuroda Completely Reinvented Her Life

The actor reflects on two decades of Gilmore Girls and the year she took a leap of faith.

In Bustle’s Q&A series 28, successful women describe exactly what their lives looked like when they were 28 — what they wore, where they worked, what stressed them out most, and what, if anything, they would do differently. This time, Gilmore Girls actor Emily Kuroda reflects on the year she decided to commit to being an actor.

At 28, Emily Kuroda completely changed her life. After years of believing she couldn't make it as an actor because she was Asian American, a chance encounter led her to take a leap of faith. She stumbled upon the the Asian American theater group the East West Players performing at her college's student union in Fresno, California, and recognizing acting as a legitimate path for her, she moved to Los Angeles and never looked back. "You should always follow your heart, even though it makes no sense," the actor, 67, tells Bustle of the decision. A few years later in 1982, Kuroda booked her first guest role on the NBC crime drama Remington Steele. What followed were years of other bit parts, playing multiple doctors and nurses on shows like Doogie Howser, M.D and The Young and the Restless. It would be almost 20 years before she landed her iconic role as Mrs. Kim on Gilmore Girls.

Not only did the part give Kuroda a steady onscreen gig, it solidified her place in television history. Though she only appeared in 43 episodes — roughly one third of the show — she was a constant presence throughout its seven seasons and appeared in the 2016 Netflix revival A Year In the Life. Below, Kuroda looks back at how deciding to pursue acting professionally helped her connect with her Asian American identity.

Tell me what your life was like at 28.

I was getting my teaching credential because I said, "That's the only thing I can do." I was married; I was going to Fresno State. I was told I could never act [because I was Asian American], and I had accepted that.

What changed that made you think you could be an actor?

I was taking my teaching classes, and I went to the student union and the East West Players were doing a little show. After that show, I said, "I was told I couldn't do this for a living." And they said, "Oh yes you can." So, as soon as my semester was over, I called them just to take a summer course. [But] I stayed. I never left.

How did you make such a huge life change?

It was so easy because it made sense to me. It felt like I was meant to be at that student union. You should always follow your instincts.

Was your husband supportive?

Oh, hell no! [laughs] That was the biggest struggle. I was working seven days a week. I was working at a bank during the day and I was going from show to show — whether I was doing props, costumes, acting, understudy. And then we would spend every minute of our waking hours working on shows.

So my then-husband came to LA because I said, "I can't leave. This is where I belong." And it didn't work out. And, you know, I got married when I was 18 because that was what you did in Fresno. It was an amicable divorce and separation, and he went on his way, and I just stayed in LA.

After making the jump to join the East West Players, did you ever think you'd get the opportunity to play a character like Mrs. Kim on television?

Oh, no. That option did not exist for me back then.

What do you think your 28-year-old self would have said if someone told you what was going to happen?

I would have just laughed in their face. I had accepted the fact that I was lucky to find a theater group. And then all of a sudden, these roles started coming up, and I just kind of stumbled my way into it. I was grateful every step of the way.

But also, my father went through the internment camps during World War II, and I wasn't allowed to speak Japanese because they didn't want me to be Japanese because of the racism, because I was born in 1952 right after the war. So I think I thought I was kind of white. And then I went to East West Players, and they're talking about racism, and I started becoming aware of it. And it woke up that whole part of me, the Asian Americanness of me that I had denied.

Was there a moment in your career after that when you felt like you'd made it?

It's different for Asian Americans — maybe not now — but then. You'll get a guest star or something and you think, "Oh, I've made it," but there weren't that many roles. I'm very lucky that I have been able to make a living acting, but it's always been a struggle. And even now I go out for parts and my agents go, "They're not Asian. This is a really good part." And I look at it and I go, "No, this isn't a good part!" [As Asians], we still rarely get the parts where we're the leads, where we have conflict, where we drive the movie. In plays, we find those roles if we're lucky enough to have them, but rarely do I find that in TV and film.

But that's why Gilmore Girls was so cool, because I went [into my audition] with a Korean accent, and [creator] Amy Sherman-Palladino said, "What are you doing?" And I said, "I'll work on it. It's a Korean accent, but it'll get better." She goes, "No, no, no, I don't see an accent at all. This is based on real people."

And the producer of Gilmore Girls [Helen Pai] is a Korean American who married a musician in a rock band. So that's why it was so refreshing, because it wasn't based on stereotypes. It was based on real people and real feeling. And just to be able to go from square one — being a mother of a teenage girl who has never dated — to her first date, to marriage, motherhood, it was such a beautiful journey that I was so grateful for. And that wasn't stereotypical at all. That does not happen very much in American TV.

[Today] we applaud directors and writers who cast Asian Americans, but a lot of times when they "go multicultural" they think they're being very progressive [when] Asian Americans get the sh*tty roles. They pat themselves on the back, saying, "Look, we're so good to minorities!" I'm like, "No! I didn't even get to read for the lead." But we're not giving up, we're still fighting ... We have not cracked that glass ceiling yet.

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed.

This article was originally published on