Books

What Is A “Hot Girl Book” & Why Is Everyone Talking About Them?

A new, hard-to-define genre is emerging before our eyes (and on our Instagram feeds).

It all started with Marilyn. As a celebrity, Marilyn Monroe existed to the public primarily as a series of images — the shot of her billowing Seven Year Itch dress, the pictures of her draped in crisp white sheets. Mostly, they were variations on a theme: “she’s hot.” But one subgenre of the Monroe visual canon stuck out to onlookers at the time: the photographs of Monroe looking hot while reading. There were the shots of the actor engrossed in her ex-husband Arthur Miller’s An Enemy of the People, cuddled up in bed with Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass collection, and, most famously, Eve Arnold’s series of Monroe lounging in a striped bathing suit, poring over James Joyce’s Ulysses. Through these photos, Monroe introduced the world to the novel idea that a hot girl could, in fact, enjoy reading.

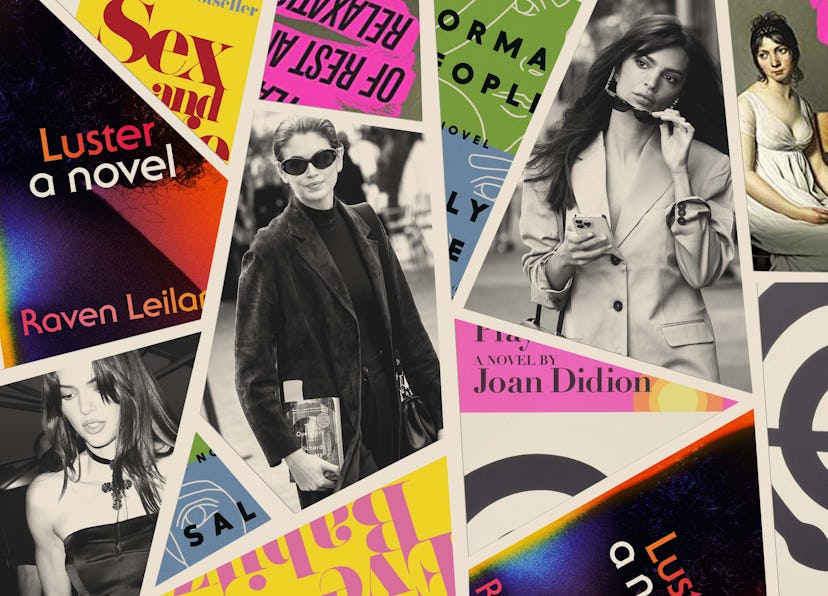

These days, it’s never been easier to be seen RWH (reading while hot), and stars like Gigi Hadid, Kendall Jenner, and Kaia Gerber have all been caught in the act. In Monroe’s heyday, people dismissed the notion that a woman could be smart and intellectual, and often argued about whether Monroe actually read the books she was photographed holding. That trend hasn’t entirely faded (see: Gawker’s “Which of These Book-Loving Celebs Are Actually Literate?”), but largely, today’s Hot Girls are celebrated for their bookish pursuits (see: “How Kendall Jenner Became the Patron Saint of Alternative Literature,” “Bella and Gigi Hadid Make Books the Hot New Accessory of 2019”). Hot Girls don’t just happen to read; they are hot because they read.

In parallel to the proliferation of women RWH, a new genre of books has emerged from the fray: Hot Girl Books. These titles — the Sally Rooney literary romances, the Ottessa Moshfegh novels of female alienation, the Jia Tolentino essay collections — aren’t solely considered hot because of who’s seen reading them; they’re deemed hot on their own merits by the millennial and Gen Z women who love them. And yet, the genre’s rise can’t be separated from that of the book-toting It Girls. Perhaps it’s the overlap between the people who follow the RWH literati and the readers who love Hot Girl Books. Perhaps it’s because Hot Girl Books confer cultural capital on those who carry them (apparently, they’re “Must-Have Fashion Accessories”). Perhaps it’s something else entirely. The genre is hard to pin down, as one Redditor seeking “recommended books for hot girls” notes: “I know this seems vague, but if you know, you just know.”

But what if you don’t just know? Below, an attempt to parse how to spot a Hot Girl Book.

The characters are hot

The protagonists of Hot Girl Books are traditionally thin, cisgendered, bookish women who are having a ton of sex. (Or as the unnamed narrator of Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation describes herself, “[I’m] tall and thin and blond and pretty and young... Even at my worst, I knew I still looked good.”) But what sets them apart from other hot girls is that they’re the kind of women who other women actually find attractive, whether it’s Normal People’s Marianne and her swath of bangs or Camilla’s waifish etherealism in Donna Tartt’s The Secret History. They’re not girls next door, cheerleaders, or prom queens. They’re the Winona Ryders of the world: Hot because they’re cool, not because they’re prime objects for the male gaze.

…and emotionally fragile

The heroines of Hot Girl Books seem to have everything going for them. They’re typically educated, attractive, and work in one of the only two fields available to women in books: art or publishing. Yet, beneath their shiny exteriors, these women are gripped by a deep, stifling malaise. Take Frances of Rooney’s Conversations with Friends, a college student and spoken word poet living in Dublin, who’s also having an affair with an older, married actor. The affair causes an anxiety she seems to take out on her flesh: picking, scratching, and gouging at it. But like in most Hot Girl Books, Rooney doesn’t diagnose her protagonist with anxiety or depression, leaving Frances’ woes unnamed. Similarly, in Luster, Raven Leilani doesn’t describe her character Edie’s reckless behaviors as anything more than self-destruction (save for labeling her an “office slut”). These aren’t the institutionalized women of Girl, Interrupted or the depressives of The Virgin Suicides, they’re just delicate and slightly damaged women. As such, they can still unproblematically be perceived as hot.

There’s a lot of sex, but it isn’t always sexy

Typically, when sex is depicted in mainstream pop culture, it’s some version of a fantasy — a mashup of vanilla-ish positions that ends with both people inevitably coming, usually at the same time. But in Hot Girl Books, sex is often messy, emotional, and sometimes even concerning, as in Lisa Taddeo’s Three Women, which charts the private carnal desires of a woman who enjoys cuckolding her husband, a teen girl being groomed by her teacher, and a dickmatized housewife. Luster, which centers on a Black millennial woman who becomes the third in an open marriage, explores our more violent urges, with Edie enjoying being punched and choked during sex. It’s a kink Normal People’s Marianne shares — though not one poor, sweet Connell can bring himself to help her with.

There’s a thinly veiled veneer of autofiction

Hot Girl Books aren’t exclusively novels — they can also be memoirs, essay collections, or even poetry — but when they are novels, they almost always border on autofiction. Sure, Torrey Peters didn’t actually decide to raise a child with her recently detransitioned partner and his new girlfriend like in Detransition, Baby, and Tartt didn’t actually bludgeon a farmer to death during a bacchanal at her small liberal arts college in Vermont, as in The Secret History. While Rooney may have f*cked a dude who wore a chain at one point (if so, good for her), in reality she’s long been married to a mathematics teacher — not in the throes of a never-ending, Normal People-style situationship. Yet what Peters, Tartt, Rooney, et al. share is that their novels are imbued with just enough of their own personal experiences to intrigue us with their maybe semi-autobiographical characters. Which leads us to…

The author has a cult of personality

Joan Didion leaned up against a Corvette while smoking a cigarette. Eve Babitz played a chess match against Marcel Duchamp in the nude. Moshfegh claimed to be an other-dimensional being. Though these methods of noisemaking are certainly varied, they all succeed in one essential Hot Girl thing: cultivating intrigue. Some express their allure through sartorial choices, like Tartt, who in one year won the Pulitzer while also making Vanity Fair’s best-dressed list for her androgynous style, or the aforementioned Didion, who famously found herself starring in a Céline ad in her 80s.

The new generation of Hot Girl authors are courting fans on social media, and particularly on Twitter. There, Happy Hour novelist Marlowe Granados can be found cheekily publicizing her book by baiting celebrities to slide into her DMs; Jia Tolentino once responded to a rebuke of Trick Mirror with so much natural charm that it earned her more fans than detractors: “A cleansing, illuminating experience to be read with such open disgust!” Hot Girl behavior, if we’ve ever seen it.