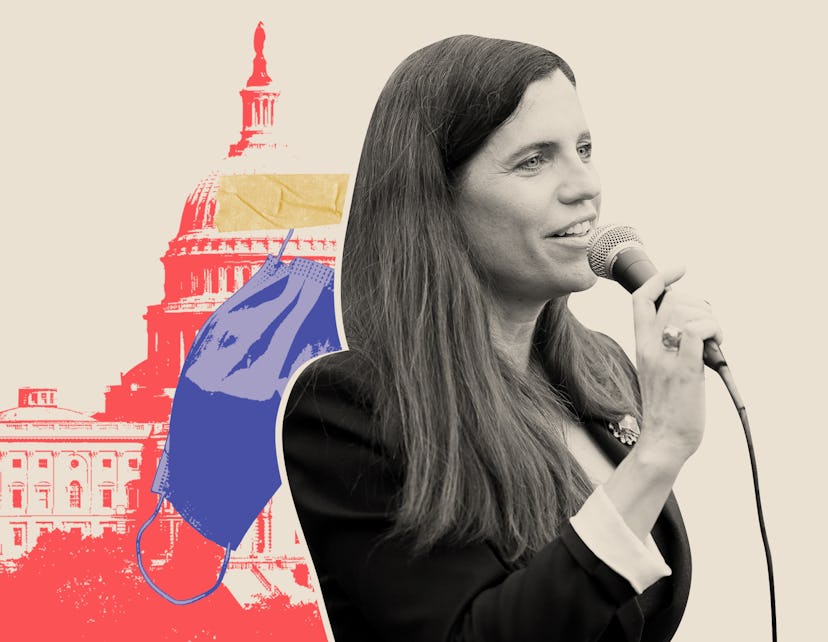

Rule Breakers

The Congresswoman Battling Long-Haul COVID

Last June, Rep. Nancy Mace was diagnosed with COVID-19. She still feels its toll.

Rep. Nancy Mace still gets winded when she takes the stairs. By the time she reaches her second-floor office on Capitol Hill, she feels like she’s just finished a sprint. Her inhales are labored. People breeze past her in the hallways in the Cannon House building. “If I'm having a conversation, you can hear me breathing,” the first-term congresswoman tells Bustle.

Mace, the first woman to graduate from the Citadel, used to exercise “profusely,” she says. Three times a week, she’d take her road bike on 30-minute rides in Charleston, S.C., clocking speeds up to 20 miles per hour. But last June, she was diagnosed with COVID-19, and save for a couple of difficult bike trips last summer, she hasn’t been cycling since.

Mace is a COVID-19 “long-hauler.” She’s among an estimated 10% of COVID-19 patients who battle symptoms for months or longer. “There was some depression there,” says Mace, 43, who flipped South Carolina’s historically conservative 1st District back to Republican control in November. “I just wasn't myself, [and] I said to myself, ‘My God, if I have to go through this for the rest of my life, I don't know what I would do.’ I don't wish it upon anybody.”

Long-haulers, who number in the tens of thousands, report symptoms like debilitating fatigue, headaches, brain fog, and depression, all of which interfere with daily life and, for many, can make keeping a job nearly impossible. Preliminary studies show that survivors face an increased risk of developing some form of mental health issue, like Mace, and of developing psychiatric conditions and neurological or psychological problems. The disease’s long-term effects are still unknown.

“I would set aside a block of time where I had to lay down and take a nap, or else I could not get through the day.”

Mace still isn’t sure how she got sick. She tested positive a couple weeks after winning her Republican primary election last June. Early reports stated a campaign staffer may have been exposed, but Mace thinks the truth is less tantalizing. “I had very few meetings that week,” she says. “The only place I [went to] was an athletic tournament in a gymnasium, which had no air conditioning, and it was in the middle of summer in South Carolina, extremely hot. You'd take your mask off to have conversations, and then put it back on. We were literally sitting on top of each other.” (One of her children, who also attended the tournament, tested positive too.)

In early June, South Carolina hadn’t yet seen an uptick in confirmed COVID-19 cases. Gov. Henry McMaster, a Republican, had begun allowing some businesses to reopen. But by July, cases spiked.

Mace’s symptoms started two days after her positive test: lost senses of smell and taste, chest pain, body aches, fatigue that left her couch-bound, swollen ankles, and dipping blood oxygen levels. “It felt like an elephant, or something very heavy, was sitting on my chest,” she says. “My oldest said, ‘Mommy, you sound like Darth Vader when you breathe,’ and that's when I started checking my blood oxygen level and realized it was under 90 and fluctuating.” (Falling below 90% is considered abnormal. Mace’s levels dipped to 87.)

As a single mom, getting sick threw her for a loop. Mace and her two children went into group quarantine. Some days, she could barely get out of bed. Friends and family helped her get food and groceries. Occasionally she could muster up energy for a game of Jenga or Monopoly with her children, ages 11 and 14.

Meanwhile, she had a campaign to run. Election Day was less than five months away, and Mace was polling neck and neck with incumbent Rep. Joe Cunningham, a Democrat. Her platform focused on pillars of contemporary Republicanism, like prioritizing the economy, securing the Southern border, and defunding Planned Parenthood.

But it took three months before she was able to shake the fatigue. Her campaign staff structured naps into her daily schedule. “Chronic fatigue is something you read about and you're like, ‘Is it imagined, or is it real?’” says Mace, who previously served one term in the South Carolina state legislature. “I would set aside a block of time where I had to lie down, or else I could not get through the day.”

It changed her campaign approach. “After having that experience, I wanted to be vocal and educate people about it, while also ensuring we were taking the right safety precautions,” she says. A quick scroll through her Facebook video history confirms a clear shift in messaging: Prior to her June diagnosis, she celebrated her primary victory without a mask, and few of her videos focused on COVID-19 or safety precautions. Since then, however, she's been masked up and speaks frankly about the gravity of the pandemic.

“There's got to be a balance between safety and health and also the economic needs of the American people,” says Mace, who won the November election with 50.6% of the vote.

But when lawmakers began lining up for the COVID vaccine in December, Mace declined to take the shot, even though a portion of early doses were reserved for elected officials. “I don't think Congress should be first in line for the vaccination,” she says. “Those who are most vulnerable — our frontline workers, our aging population, those who have underlying health conditions — need to get the vaccination first.” She intends to get the vaccine when she’s eligible in South Carolina. Last week, she voted against the COVID-19 relief bill, which she called a “$1.9 trillion spending spree” for progressives.

Mace now feels “95% better,” she says. She lives part-time in Washington, D.C., and her “workouts'' focus on daily tasks, like walking and taking the stairs in lieu of elevators, decisions she hopes will increase her endurance. Of late, she’s made headlines for using Twitter to question Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s account of the Capitol insurrection, shortly after the two co-penned a bipartisan letter to the House Chief Administrative Officer and the Office of Employee Assistance to improve mental health resources to Capitol Hill personnel following the Jan. 6 attack. (Mace thinks the GOP should distance itself from Trump because of his role in it.)

June will mark one year since her COVID-19 diagnosis. As warmer temperatures approach, she hopes to get back on the bike. “With [South Carolina’s] sun and beautiful weather,” she says, “to not be able to do that, it’s very frustrating.”

This article was originally published on