LGBTQ+ History Month

Meet The Instagrammers Behind Black & Gay Back In The Day

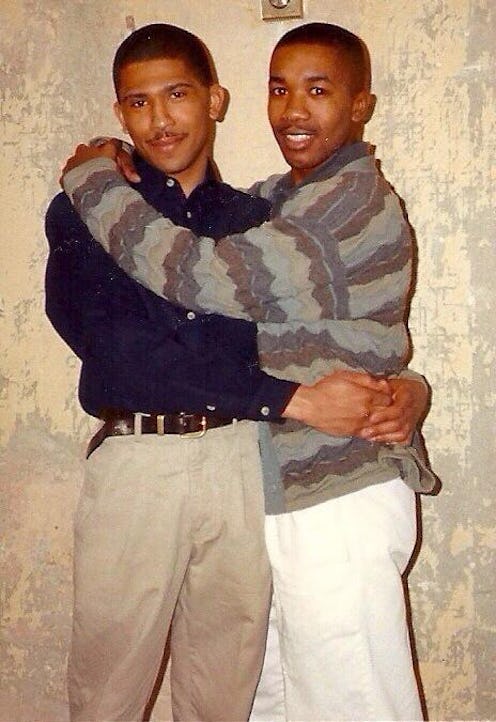

And why they decided to start a digital archive that celebrates, honours, and remembers the Black British queer community.

Despite only having been around for just over a month, you could say the foundation for @blackandgaybackintheday started three years ago, when founders Jason Okundaye and Marc Thompson first met. At the time, Okundaye was working on his dissertation, focused on HIV rates amongst Black men who have sex with men in the UK. He sent Thompson, a prominent HIV sexual health advocate and director at The Love Tank, "an enthusiastic message" asking to interview him about his work. "Since then he's just become a constant source of guidance and support," says Okundaye, sharing not only his 30+ years experience of working in the sexual health sector, but also stories about his life and experience.

“Through Marc’s stories, I realised that there were whole communities that I knew nothing about,” explains the now established writer over Zoom, “and I wasn’t going to find them in a book, or in the lecture, or YouTube.” But now you can find some of those stories on Instagram, via their newly minted digital archive, which has gained more than 5,000 followers. Launched to coincide with LGBT+ History Month, it celebrates the Black British queer experience between the 1950s to 2000 as it truly was: with stories of love, friendship, and joy.

"Like most of my ideas, it came to me in the shower," says Thompson of the archive's title and handle with a playful smile. Having just watched It's A Sin, he was reflecting on the music (he's since created a playlist alongside his friend Calvin Dawkins, aka DJ Biggy C, that more accurately reflects the Black gay underground nightlife scene they remember, rather than what the show reflects), the safe spaces he and his friends relied on in the 1980s, and his experience more generally. "That led to a bigger thought in my mind about the representation of Black and brown people throughout our history, and then realised it was LGBT History Month. And I remembered [the 2016 exhibition at the Royal Festival Hall] Black in the Day, and I just thought 'wouldn't it be really cool if there was something specifically celebrating Black queer people?'” And with that, he launched the account.

"Jason really sweetly messaged me and was like, 'Yo uncle, can I help you with your Insta page?'" says Thompson with that big grin again. "And I said, 'Why? What's wrong with it?'" Their ability to laugh and enjoy what Thompson calls "intergenerational exchanges" – he's 26 years Okundaye's senior – is really at the heart of their endeavour. Whether it's an exchange of knowledge or swapping music – Thompson's Jade for Okundaye's Ivorian Doll, most recently – the two have a clear bond and singular purpose.

"This isn't about who was big on TV or who was famous," explains Okundaye, "this is about reflecting everyday life in Britain. Those archives exist, but we wanted to have that for the Black queer scene too, and to remember and honour it."

Here, Okundaye and Thompson reflect on their aims for the archive and aspirations for its future.

On the aim behind Black & Gay, Back In The Day

Jason Okundaye [JO]: "My aim is always to make us rethink how we think about Black British history. Often we think about major moments of race relations and riots legislation, but none of us would ever define our lives in this way. We define our lives by our social networks, our community, who we love and fall out of love with... The pandemic has made me realise what matters in the life, and when I look back it's not 'I got my degree' or 'I achieved this,' it's the small things.

"For me, @blackandgaybackintheday is a way for thinking about the future and how we record things. It's also a message to people of my generation to keep taking photographs, to keep documenting our existence – the happy memories, the mundanity of everyday life, the house parties and the rave leaflets – because it's so easy for so many of these stories to become lost. Black British history is more than slavery and colonialism. And it's not just Black gay history, it's also British history."

On the challenges of building an archive and creating a safe (virtual) space

Marc Thompson [MT]: "We explicitly chose pre-2000, in part because we wanted analogue images, but also because we felt that there was a generational cutoff point as well. Initially, I started by asking friends who I knew might have an archive, and we subsequently put a call out on the page.

"But it's been a challenge to get submissions. We've had a handful of people that have been incredibly generous and dug really deep and given us stuff – big shout out to Ajamu X – but one of the issues we've had and have going forward, is around permission, and about people wanting to be visible. This is a generation of people who were not as visibly out as the current generation are – this is pre-Insta and pre-Twitter – and still carry some of that internalised homophobia or maybe some of that internalised shame. And even if they don't, they may still perceive that they are in spaces where to come out might be unsafe for them to do so.

"We are really mindful and really careful about what we're putting out. We try to seek permission as far as we can, and we try to make sure that anything we're putting out comes from the people who have given it to us. Jason and I have spoken about wanting to make sure that we're truly representative, so you know we are trying to get more women and people from the trans community involved as well."

On Black & Gay, Back In The Day's future

MT: Right now, we're about sustaining it as it is. But I'd love to see this as a full exhibition somewhere with oral history attached to it. Also maybe a book?

JO: For me, it doesn't have to be made into this bigger project, because it's a big enough project in and of itself. Obviously we'd love for it to get onto something, but it has to be organic. I wouldn't want to do anything that compromises the integrity of the project, I always want it to be what it is. We'll keep up for as long as we can, but also only for as long as necessary and the project will go where it goes.

MT: My hope really is that younger people start being more curious, start digging down, and reaching out to elders to ask these questions. And I also hope that it enables the elders to either reconnect with each other to reengage with the scene and community, and to do what I'm doing with Jason, which is to start building up these intergenerational relationships because they're so healthy for us. They are what sustain us and what will keep us going, because this world is pretty crap to us and we need each other.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

This article was originally published on