Rule Breakers

The Things They Carried

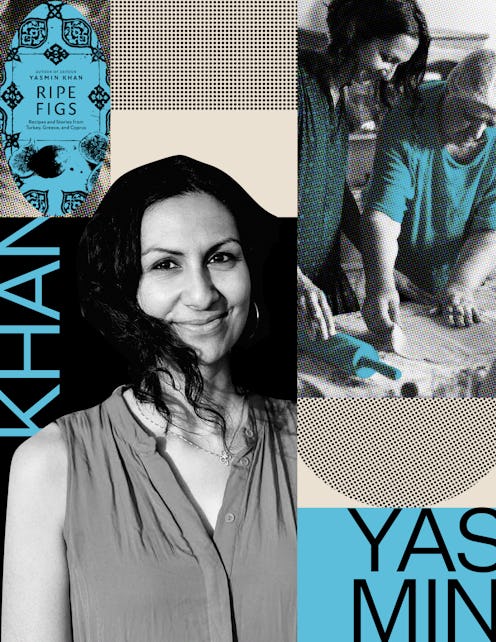

In her new Mediterranean cookbook, Yasmin Khan centers the stories of refugees.

In conducting research for her new cookbook, Yasmin Khan visited refugee camps on Lesvos, a Grecian island in the Aegean Sea. Roughly 6 miles from Turkey’s shore, the island has been ground zero for sea arrivals to Greece and continues to host thousands of migrants. She interviewed people about the choice to leave their homes, and the recipes they carried across borders, when carrying anything else could have meant certain death. She spoke with local organizers, like Lena Altinoglou, whose restaurant features dishes from Syria, Pakistan, and Afghanistan, courtesy of the refugees she employs.

“I found it like an incredibly traumatic experience,” says Khan of the 2018 trip. “The fact that this is taking place on European soil, a hugely rich part of the world, was really shocking to see.” I ask if she ever gets pushback to this culinary approach. “No,” she says. “Food is political. I use food as a way to help us understand ourselves and the world around us. That's the whole premise of my work.”

In her new cookbook, Ripe Figs: Recipes and Stories from Turkey, Greece, and Cyprus, Khan shares more than 80 recipes from the region, like eliopita, an olive-infused Cypriot bread, and kaymak, a Turkish breakfast spread made from buffalo milk. Between dishes, she pens essays about her travels, global migration, and the people she met. “Being uprooted from one’s homeland is an unsettling experience,” she writes in the book’s introduction. “People often become attached to things that help them to maintain a sense of identity. ... [And] perhaps nothing provides more of a sense of identity than food.”

Beginning in 2015, Europe saw an influx in refugee arrivals, largely from war-torn countries in the Middle East, such as Syria and Iraq. By 2016, the UN Refugee Agency estimated that over 5 million people had landed on European shores to escape violence and persecution. Refugee camps became overcrowded and under-resourced, and coastal countries like Greece struggled to manage growing populations. Khan, in turn, booked a trip to Athens.

Her humanitarian disposition is clear in her work. Instead of painting her travels with the patina of an Instagram jetsetter, she is honest. During our phone call, she tells me that she’s had an exhausting morning taking interviews from home in northeast London. She’s unrehearsed, taking long pauses before answering.

“There's an intimacy that gets formed in the kitchen when you're slicing tomatoes or dicing onions,” says Khan, 40. “You can hear them sizzling in a pan, and the smells and fragrances are jumping-[off] points for conversation.”

She spent the beginning of her career as a London human rights activist, focused on the Middle East. But around age 30, after 10 years of advocacy, she hit a wall and was diagnosed with chronic fatigue syndrome. Shortly after, she packed her bags and embarked on a new adventure — and, with it, a new career in cookbooks.

Between Ripe Fig’s recipes, Khan’s prose is filled with the same candor — like, for example, when describing a beautiful Greek island port, she also mentions the European Border and Coast Guard Agency ships that patrol the waters for migrants. In one chapter, Khan describes some of her worst travel days, following a miscarriage. She soothed herself by indulging in figs, which remind her of home and family.

A few months later, Khan was in Istanbul, cooking lamb meatballs with a Turkish publisher, Berrak Göçer, who’s Kurdish. (Turkey’s Kurdish community is a distinct ethnic group indigenous to the Middle East, but without its own state.) Over a bowl of hot, minty yogurt soup, they talked about “otherness” and growing up in multicultural households [Khan’s mother is Iranian, her father Pakistani]. She asked if Göçer hoped for Kurdish independence.

“She was like, ‘Actually, it's just about people having equal rights within Turkey,’” Khan says. “It was a simple premise, but so powerful to me, and made me question the ideas I had about nationalism.” The author pauses, perhaps remembering pre-pandemic life. A full kitchen, now a memory, is one of her favorite places to have conversations about identity. “And the food was delicious.”